WASHINGTON — Rumors that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. is close to broke — which have increasingly gained traction as the level of federal reserves has declined — appear greatly exaggerated.

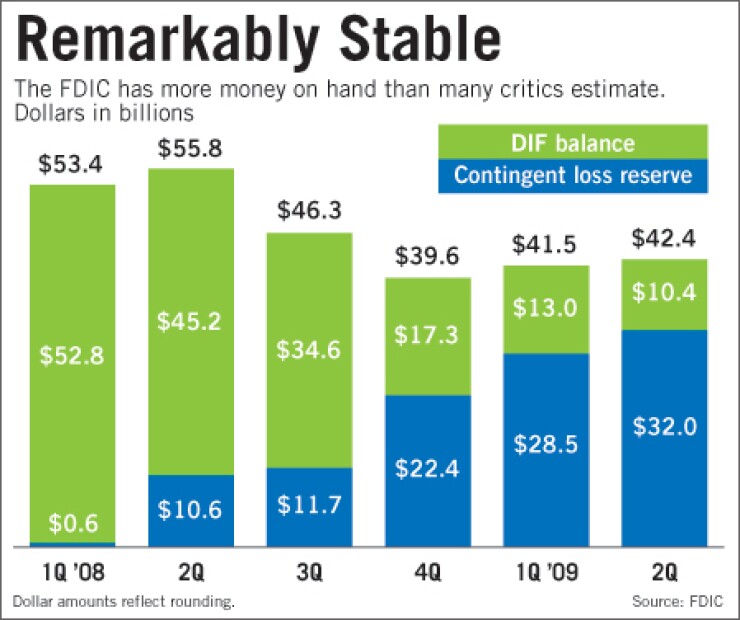

Though on paper the agency had only $10 billion left at the end of the second quarter to deal with an expected rash of failures, the FDIC actually has more than $42 billion on hand — only $4 billion less than it had nine months earlier at the height of the financial crisis.

At issue is the FDIC's accounting methodology, which forces the agency to remove money from the Deposit Insurance Fund to prepare for a failure if a bank receives a poor Camels rating. As the number of troubled banks has increased, the FDIC has set aside more of its money, leaving the Deposit Insurance Fund looking depleted and increasing anxiety about the state of federal reserves.

Many observers — and the FDIC itself — have said that the news media and some analysts are overlooking loss reserves as failures mount, assuming incorrectly that each new bank collapse is at risk of exhausting the fund.

"The media loves to look at the fund balance. I think you have to look at the whole picture," said Paul Miller, a managing director at Friedman, Billings, Ramsey & Co. Inc.

The FDIC is attempting to turn that perception around. Though it seldom mentioned the set-aside for expected losses — which it calls the "contingent loss reserve" — in the past, FDIC officials emphasized during the most recent quarterly report that those funds were still available to the agency.

"We have been trying to stress recently that people need to look at both" federal reserves and the contingent loss reserves "to get a picture of what's available for us to handle the cost of bank failures," said Art Murton, the director of the FDIC's division of insurance and research, in an interview. "We entered this crisis period with slightly more than $50 billion in our fund — basically, there was very little reserve there — and now we are in the low 40s. That's not a huge decline. But because we have tried to reflect the cost of the failures we anticipate a year ahead, it looks like more has happened than actually has happened. That's really lost on people."

Though the contingent loss reserve bedeviled the industry during the savings and loan crisis, when the agency had to set aside so much that the then-two deposit insurance funds were exhausted, it has received little attention during the current crisis.

Until recently, that was likely because the figure was negligible. In March 2008 the agency's loss reserves totaled just $600 million, while the DIF held $52.8 billion. But with more banks' Camels ratings slipping, the contingent loss reserve has skyrocketed over 5,000%, to $32 billion at the end of June.

How the loss reserve is calculated is a tricky task for the agency. Under generally accepted accounting principles, the FDIC is required to designate as a liability the money it expects to lose to failures over the next four quarters.

The agency tasks a special panel, known as the Financial Risk Committee, with meeting to determine how much loss reserves are needed. The committee meets roughly twice a quarter. It begins with all of the institutions on the "Problem Bank" list, which are those with Camels ratings of 4 or 5. Last quarter there were 416 institutions on the list.

Using failure trends over the past two years as a guide, the FDIC puts banks in one of five buckets in order of failure probability. The first four buckets are: banks with Camels 4 ratings and capital ratios above 2%; 4-rated banks with capital ratios below 2%; 5-rated banks with capital above 2%; and 5-rated banks with capital below 2%.

Banks rated 5 with capital below 2% have a very high chance of failure, while those rated 4 and with higher capital have less probability. Each institution is given a rough loss estimate should it fail, but that estimate is adjusted by the failure probability of its bucket. A fifth category contains institutions that for a variety of reasons have a 100% probability of failure.

Murton said the panel is given a certain amount of discretion to adjust a bank's expected loss based on supervisory information. Typically, an institution may jump between buckets in a given quarter, and the agency will have to reserve more or less money.

When and if the institution fails, the agency pays for its resolution from that reserve, not from the DIF's balance. "Sometimes" the projections are "high, and sometimes they're low," Murton said. "Nevertheless, there's money set aside. If you forget that, you tend to have a bleaker picture of what our resources are."

The estimates are critical to the health of the fund. If the FDIC underreserves, a failure could end up drawing more than expected from the DIF. If it sets too much money aside, there is less money available in the fund to deal with unanticipated failures, potentially undermining public faith in the fund and causing banks to pay more in premiums to replenish it.

Some observers warned the loss reserves are just an estimate. "They're a guess. They can be right or wrong," said George Pennacchi, a University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign finance professor.

For some recent failures, the agency appears to have erred on the side of caution, putting more money in the contingent loss reserve than the actual failures will cost. When the agency announced the failure of the $25 billion-asset Colonial Bank on Montgomery, Ala., on Aug. 16, it said that the estimated loss to the DIF of $2.8 billion was less than it had reserved.

Others said the contingent loss reserves also do not sufficiently account for revenue the agency is receiving.

"One of the things the loss reserve does not take into account … is future premium income," said Bert Ely, an independent bank consultant based in Alexandria, Va.

Ely argued that since the loss reserves are supposed to project failures over four quarters, they should project assessment income over the same period.

But Murton said GAAP rules bar the agency from doing that, and a more extensive accounting for premiums would have other consequences.

"I believe if we booked that future income, the banks would have to expense it," he said.