WASHINGTON — Though the banking industry eked out a profit and boosted capital during the third quarter, a retreat from risk and a significant drop in overall lending proved that it is still far from business as usual.

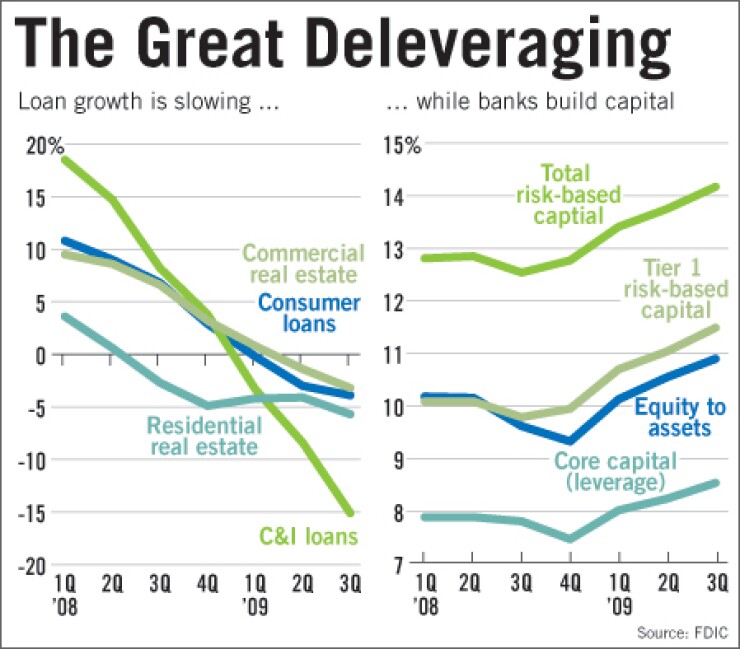

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s Quarterly Banking Profile showed an industry still in the midst of deleveraging. Loan balances made the largest quarterly decline on record, capital ratios rose sharply and institutions looked to the safety of Treasury securities and their Federal Reserve banks.

Though FDIC Chairman Sheila Bair lauded the industry for "charging off problem loans and building capital and reserves" — and announced the relaunching of a plan to help banks purge troubled loans — she stressed that institutions need to get back to lending, particularly to commercial customers.

"There is no question that credit availability is an important issue for the economic recovery," Bair said. "We need to see banks making more loans to their business customers. And this is especially true for small businesses that rely on FDIC-insured institutions to provide over 60% of the credit they use."

The third quarter put the industry back into positive earnings territory, as institutions made $2.8 billion after posting a $4.3 billion loss a quarter earlier and earning just $879 million in the third quarter of 2008. The FDIC said increases in net interest margins and values of securities holdings helped drive the improvement and that growth in noncurrent loans slowed.

But the report also made clear that more failures are on the horizon; "problem" institutions grew by one-third, to 552, and assets held by these banks jumped 15%, to $346 billion.

The agency also confirmed a deficit in the Deposit Insurance Fund — the first time it has drifted into negative territory since the savings and loan crisis — and it warned that both losses on failed banks and provisions for future losses continue to be high.

"Today's report shows that, while bank and thrift earnings have improved, the effects of the recession continue to be reflected in their financial performance," Bair said.

Several factors indicated that banks are reluctant to deploy capital. As overall industry assets fell for a third straight quarter, loan balances dropped 2.8%, to $7.4 trillion. This was the biggest percentage decline since 1984, when the agency began reporting such data; balances were down 7% from a year earlier.

Lending dropped in most categories. Commercial and industrial loans were down 6.5%, to $1.27 trillion. Residential mortgage loans declined 4.2%, to $1.93 trillion. Construction and development loans totaled $492 billion, off 8.1% from the second quarter. Credit card loans fell 1.2%, to $393 billion.

Meanwhile, institutions expanded their positions in conservative assets, and improvements in securities values helped boost capital levels. Balances at the Federal Reserve banks grew 36.7%, to $531 billion, and holdings in Treasuries grew 49%, to $86.6 billion. Total equity capital grew 2.9%, to $1.46 trillion, helped in large part by the appreciation in banks' securities portfolios. The agency said regulatory capital ratios are at their highest levels in the 19 years that the current capital standards have been in place.

Ross Waldrop, the FDIC's senior banking analyst, said the capital growth is a result of banks' conservatism.

"There is some deleveraging, which, all things being equal, has an upward effect on capital ratios," Waldrop said at the briefing. "We also noted a shift toward less risky assets in the third quarter: an increase in balances with the Federal Reserve banks, an increase in banks' holdings of U.S. Treasury securities so that the overall risk weighting of their assets also diminishes. That has a positive effect on regulatory capital ratios."

Richard Brown, the agency's chief economist, said the capital improvement shows "progress in balance sheet repair" and should lead to more credit being available soon. "Higher capital levels put institutions in a better position to lend — clearly recognizing losses, moving problem loans off the balance sheet," he said. "These are all necessary things that institutions have to do in a situation of credit distress. So we're looking for the industry to be in a better position to lend going into next year."

Bair said the balance-sheet cleansing would probably continue, and she unexpectedly announced the agency is planning to attempt subsidized loan sales again for open institutions.

The Legacy Loans Program — part of the government's broader plan to expunge layers of bad credit from the financial system — had initially stalled this year over disagreements about pricing and a dearth of institutions interested in selling their problem loans.

To date, the FDIC has done two high-profile deals — with the agency providing financing to investors — but the transactions have involved failed-bank assets. Bair indicated, however, that she has plans for an open-bank facility to get off the ground early next year.

"I'm hoping that we can start launching the Legacy Loans Program in the first quarter of next year," she said at the briefing. "We need to be very careful with this. The board is considering right now eligibility requirements, how to prioritize institutions that we'd like to see using the program. So there are still some policy issues that need to be dealt with."

But Bair emphasized that "cleansing balance sheets is absolutely necessary to strengthen the industry's capacity to lend to businesses and consumers."

The report also detailed the insolvency of the Deposit Insurance Fund and signaled that more bank failures lie ahead. The FDIC set aside $21.7 billion for future losses tied to failures, which was nearly double the second-quarter provision.

The loss reserves drove an $18.6 billion decline in the Deposit Insurance Fund's balance, to a deficit of $8.2 billion, which pushed the ratio of DIF capital to insured deposits down 38 basis points, to minus -0.16%, its lowest level since June 1992. With the loss provision, the agency still has $30.7 billion to handle failures. It also is acting on a plan to bring in $45 billion by requiring institutions to prepay three years' worth of deposit insurance premiums.

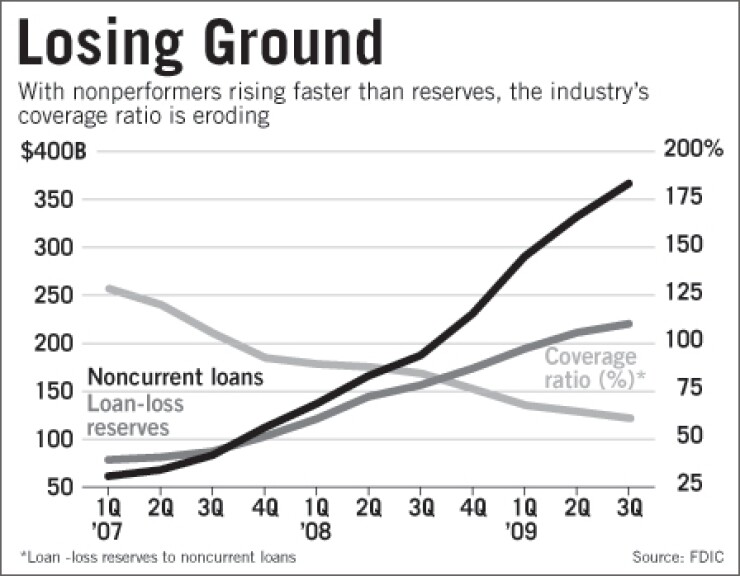

Bair said "eroding loan quality" is still the most prominent factor affecting earnings.

The industry's annual net chargeoff rate rose 15 basis points, to 2.71%, its highest rate in any quarter since call report requirements began in 1984. Net chargeoffs in the quarter grew more than 80% from a year earlier, to $50.8 billion. Chargeoffs for commercial and industrial loans rose 117% from the year earlier, to $8.57 billion; home equity lines of credit, 78.4%, to $5.1 billion; credit cards, 78%, to $9.9 billion; construction and development loans, 68%, to $7.6 billion, and mortgages, 63%, to $9.4 billion.

Loss provisions exceeded $60 billion for the fourth straight quarter. The $62.5 billion of loss provisions was 22% higher than a year earlier but 7% lower than in the second quarter.

The industry's noncurrent loans rose 10.5% during the third quarter, to $367 billion, and comprised nearly 5% of all loans. This was the highest noncurrent rate in the 26 years since such data has been collected. Noncurrent C&I loans rose 19%, to $45 billion, and noncurrent mortgages rose 13.9%, to $155 billion.

Still, the growth in bad loans may have peaked. The FDIC said that the increase "was the smallest in the past four quarters, as the rate of growth in noncurrent loans slowed for the second quarter in a row."

Other positive signs included margin improvement. The FDIC said the industry's average net interest margin of 3.51% was the highest since 2005. Almost two-thirds of the industry had higher margins in the third quarter than in the second. This fueled a 4.8% rise in net interest income from a year earlier, to $100 billion. Noninterest income rose 6.8% from a year earlier, to $62 billion, while noninterest expenses dropped 1.7%, to $92 billion, the first year-over-year decrease since the fourth quarter of 2006.

Despite continued struggles, Bair predicted the situation may improve next year.

"For now, the credit adversity that we have been observing for some time remains with us. And we expect that it will be at least a couple of more quarters before we see a meaningful improvement in that trend," she said. "There are no quick fixes here."

She said regulators must focus on effectively supervising institutions, quickly and efficiently resolving failing institutions and ensuring the DIF has adequate resources. "Despite these challenges, and depending on the economy, I am optimistic that if we address these problems head-on, we will see clear signs of improvement in bank earnings and lending in 2010," she said.