-

Industry groups are calling on CFPB to lower the thresholds it will use to designate which firms will be included in its nonbank supervision program.

May 3 -

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau said it plans to follow the Justice Department's lead in pursuing fair lending violations when a policy has a disparate impact on a group of borrowers, unintentional or not.

April 18 -

Three years after shutting down its indirect automobile lending unit because it lacked scale, First Niagara Financial Group (FNFG) in Buffalo is jumping back into the business in a big way.

March 28

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is probing whether the country's largest banks are party to discriminatory car loans, according to industry participants and attorneys.

The previously undisclosed investigation focuses on indirect auto lending, a business in which auto dealers underwrite car loans and then sell them to banks. Consumer advocates

Allegations of discriminatory lending may appear to be a natural fit for the CFPB, but its inquiries into banks' auto lending practices come with a significant wrinkle. Since banks do not originate the loans, they are not well positioned to rein in the alleged misconduct on their own, according to both consumer advocates and outside attorneys working on the issue for banks. Rules prohibiting banks from paying more for loans that carry "marked up" interest rates would do more than enforcement actions to prevent misconduct, they argue. Politically, however, attempting to impose a ban would put the CFPB into direct conflict with the powerful auto dealers' lobby.

"A lot of lenders [banks] don't really like this model," says John Van Alst, an attorney for the National Consumer Law Center. "But there's no way out for them."

"The only way to fix this is a simple rule that applies to all auto creditors," argues a financial industry attorney familiar with the probe who requested anonymity given its sensitivity.

The CFPB has not publicly acknowledged that it has an auto lending investigation underway, much less whether it's geared to rulemaking or enforcement. But in an email, CFPB spokeswoman Jennifer Howard said that the bureau is aware of the "history" of dealer markups, and is concerned that "the practice has historically been found to affect women and people of color more than others."

The Federal Trade Commission is also looking at auto lending, and last year held a series of roundtables where it called for participants to submit data on auto lending. It received little in return.

Enforcement fears

What has bankers and their attorneys especially on edge is the sense that the CFPB appears to be looking to take enforcement action rather than a rule-making approach to the matter. The bureau's early document requests suggest that it "wants to put hides up on the wall," says one outside attorney who represents banks.

At the crux of the controversy is the practice in which auto dealers underwrite loans and sell them at a "wholesale" rate to lenders. If dealership employees convince borrowers to pay more than the wholesale rate of interest, the dealer and the bank split the extra profit known as "dealer participation" or "dealer markups."

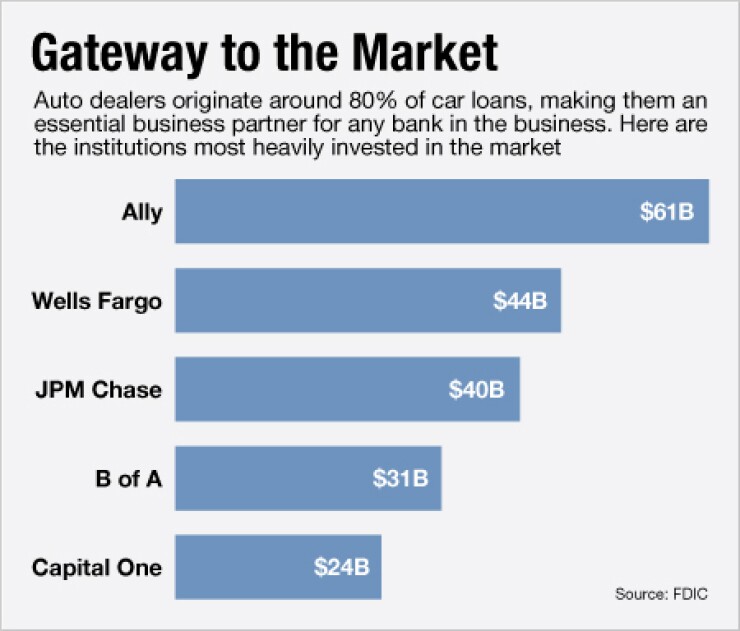

It's a big business. FDIC-insured banks alone hold more than $300 billion in auto loans, with dealers originating nearly 80% of the new credit. Some indirect loans are written at the wholesale rate, but in total those carrying markups earn dealers billions of dollars a year in additional interest.

Exactly how much dealers earn from markups, and who they earn it from, is hard to say. Dealers do not disclose the size of markups or collect data on the races of their customers. In the absence of such statistics, consumer advocates and auto dealers have produced wildly divergent estimates on the size and scope of the alleged problem.

The Center for Responsible Lending last year estimated that markups cost consumers $25 billion in 2009. The National Automobile Dealers Association

Raising suspicions that markups disproportionally hurt minorities is clear evidence that racial disparities have done just that in the mortgage industry. Lumping on extra interest on auto loans would closely resemble the former practice in home lending of imposing "yield-spread premiums," or extra fees that banks used to pay mortgage brokers for locking borrowers into above-market interest rates. Yield-spread premiums were banned two years ago, in part because of evidence that they harmed poor and minority borrowers.

"Any time you have discretionary pricing, you run a significant risk of fair lending concerns," says Christopher Kukla, an attorney with the Center for Responsible Lending. "You can look at this from a fair lending perspective or you can look at it from a consumer protection perspective. There's an issue however you play it."

The CFPB appears to be of the same mind, according to attorneys and other banking industry participants who asked to remain anonymous because of the legal and political sensitivity of the review.

Because of the lack of good data on markups, any regulatory action by the CFPB would require a lot of research in advance. The bureau has already requested a slew of documents from major indirect auto lenders including Capital One (COF), according to people in the banking industry who are familiar with the CFPB probe. Banks that are leading players in the indirect auto lending market declined comment, including Capital One, JPMorgan Chase (JPM), Wells Fargo (WFC) and Bank of America (BAC).

What concerns bankers, say lawyers and others, is that the CFPB isn't taking the collaborative approach it recently adopted in studying overdraft fees. For that review, the bureau asked top banks to fill in questionnaires with specific data. This time around, it has requested masses of documents of the sort that would be needed to make a legal case against banks.

For the CFPB, taking legal action against lenders could have advantages over rulemaking. If the bureau were to push for an outright ban on markups, it would infuriate auto dealers — a powerful Washington constituency over which it lacks jurisdiction. With more than 16,000 mostly affluent members spread throughout the nation's congressional districts, the National Automobile Dealers Association and its allies previously bested CFPB proponents in winning exemptions from the bureau's oversight.

The trade group argues both that flexible loan pricing is good for consumers and that its members do not force banks to allow the practice. Paul Metrey, NADA's chief regulatory counsel, says he has not heard any such banker complaints.

Markups are by no means the only way that banks compensate dealers for originating loans, argues Paul Metrey, NADA's Chief Regulatory Counsel. "There are a large number of finance sources in the marketplace that employ other approaches to compensation, including many that compensate dealers in the form of a fixed fee," he says.

Anand Raman, an attorney who says he represents at least one financial institution receiving CFPB scrutiny on auto lending, says that for their part banks are simply aiming to avoid a fight.

"The CFPB is going to have to balance the issue of notice and fairness to the industry against a desire to get some quick results in the form of enforcement actions," says Raman, co-head of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom's consumer financial services practice.

Troubled history

There are precedents for both the CFPB's review and for banks' fear that they might get blamed for any discrimination it uncovers.

There may be no logical reason to mark up loans based on a customer's race, but a

The cases were brought by the National Consumer Law Center, which started looking at markups in the context of racial discrimination in the late 1990s.

NCLC attorney Stuart Rossman, who helped oversee the litigation, says he and his colleagues believed that it was inherently unfair for dealers to mark up loans. But the NCLC concluded that only a suit alleging fair lending violations would survive in court, and that there were simply too many dealers to sue. So the consumer law group made a tactical compromise: Instead of suing the dealers for allegedly steering minorities into loans based on race, it sued the lenders who purchased the credits.

"The banks said 'How can you bring this against us? We can't know the race, gender or age of the person we're lending to,'" Rossman recalls. He argues that lenders had been willfully blind to signs of discrimination.

NCLC attorneys concluded that dealers were twice as likely to mark up interest rates on minority borrowers' loans as they were to do so for white customers. What's more, loans to minorities were marked up by twice as much as those for white borrowers, the NCLC found. Lenders in the cases disputed the validity of the plaintiffs' statistical methods, but eventually settled all of the suits.

Between 2003 and 2007, NCLC attorneys negotiated settlements from Nissan, Ford, Honda, GMAC and others that limited the size of lenders' future markups.

After years of negotiations with auto lenders, Rossman says, he came to believe lenders viewed markups less as a profit center than as a necessity to earn dealers' business.

"We always had the feeling that, while the auto finance companies wanted to win, it wouldn't have broken their hearts if a court told them they couldn't pay for markups anymore," he says.

Asked if the banking industry would oppose banning markups, the American Bankers Association declined to take a position. But if the CFPB or other federal officials have concerns about markups they would be best served by addressing them through rulemaking, says Richard Riese, an ABA senior vice president handling regulatory matters.

Enforcement actions are "a poor vehicle for trying to develop comprehensive market standards," says Riese. "If [regulators] really want to … understand how this market operates, and how it should be regulated, that would have to involve getting information from the dealers," he says.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau can't do that directly, because it lacks jurisdiction. Dealers are primarily regulated on the state level and by the rulemaking authority the Federal Trade Commission authority was granted under Dodd-Frank to make rules related to unfair, deceptive, and abusive sales practices. If the CFPB wants to gather data or make rules on indirect auto lending, it will have to work through the banks.

Limited market

The contemporary auto lending market was shaped decades ago. Automakers had exclusive rights to finance cars until the 1960s when dealers argued to the Justice Department that this franchise represented a restraint on trade.

Dealers began cooperating with banks and settled on markups as a way to maximize profits for both. If dealers could steer customers into higher interest loans, banks would pay more for the credits. Banks and auto makers' financing arms ended up with higher-yielding loans and dealers received upfront a portion of the future revenue stream.

The arrangement turned out to be more beneficial to dealers than banks. People who are charged above-market rates turned out to be above-average default risks. For banks it wasn't an especially attractive proposition.

Plenty of lenders have tried to rein in the markups, including Nissan Motor Finance Corporation. After noting that higher markups were correlated with greater loan defaults, the company unveiled its "Customer First Financing Program" in the early 1990's. Under its terms, dealers were required to pass Nissan Motor's wholesale interest rate on to the borrower with no markups. Instead, Nissan would compensate dealers who offered loans under its terms.

"Negative dealer reaction" to the Customer First program caused an "immediate and significant loss of business for NMAC," an executive conceded in depositions for the NCLC litigation. So Nissan switched back to paying markups — the practice over which it was later sued.

"Everyone who tried to give [markups] up voluntarily got blacklisted" by dealers, says Kukla.

Industry participants and attorneys representing large banks say that, as with mortgage yield-spread premiums, markups are not worth the fight. In the end, lenders are more intent on increasing loan volumes than in the controversial markups.

If the CFPB proposed a rule banning markups, major banks are unlikely to object, industry attorneys say. Assuming the agency is able to extend its authority over non-bank car financing companies, the banks would remain on a level playing field.

Given that the alternative of enforcement actions and allegations of racial discrimination, some bankers have even considered publicly endorsing and end of markups, industry sources say. The main obstacle is the risk of getting into a fight with car dealers, who have staked out firm opposition to any restriction on markups.

"Dealer participation, while prevalent in the marketplace, does not harm consumers and there is no credible data to suggest otherwise," NADA stated in a March, 2012

For the CFPB to challenge that position would take political capital as well as data. In the run-up to the CFPB's creation, auto dealers staunchly opposed being placed under the bureau's authority. They won handily.

"The political reality is that those of us who have fought against an auto dealer carve-out can't prevail," Rep. Luis Guiterrez conceded in June of 2010, shortly before proponents of a consumer protection bureau threw in the towel on dealer regulation.

The NCLC's Rossman and the CRL's Kukla both concede that a rule banning markups would face stiff dealer opposition. But rulemaking is the only way to solve the alleged problems with markups, they say — banks can't stop the practice by themselves. Spokeswoman Howard said the CFPB is mindful that any action on indirect auto lending would need to be comprehensive.

"As in all market-wide issues, if action is needed, we want to act in a way that promotes a level playing field for all lenders, both banks and nonbanks," she wrote in an email.

Consumer advocates see the question of whether the CFPB takes enforcement action against banks as a secondary matter. Kukla says he doubts the CFPB is intent on taking punitive action.

"Sometimes you have to build the record to support the rulemaking." he says. "If [the CFPB] gets enough information to show that this causes consumer protection issues, and that banks are involved in the purchase of these loans, the CFPB could look at whether to issue a regulation."

For bankers, the key issue is whether the bureau intends to take the enforcement route in advance or in lieu of rulemaking.

"The CFPB has stated that it is not intending to play a game of 'gotcha,' but only time will tell," says Skadden's Raman.