-

Big businesses' mixed feelings about their large bank partners are especially obvious when the conversation turns to proposed reforms of money-market funds, which corporate treasurers say could increase the power of "too big to fail" banks.

August 21 -

If very different lines of business are walled off from one another, conflicts of interest and risk can be mitigated without losing any of the benefits of one-stop banking.

August 17 -

The Clearing House made the case for big banks' "social utility," arguing that banking behemoths pay dividends in efficiency, flexibility, and innovation.

July 27 -

The CEOs who lead our largest banks ought to be spending their time trying to get ahead of the next problem and righting their corporate cultures. If they don't, it may be only a matter of time before Congress breaks them up, argues Editor-at-Large Barbara A. Rehm

July 25

Big banks love their biggest customers, but the feeling isn't always mutual.

That has become evident as the nation's largest banks try to fend off a

In their defense, the big banks' trade groups and executives have argued that their very size is a huge asset to the economy. Banks with more than $50 billion of assets "provide $50 billion to $110 billion annually in benefits to companies, consumers and governments," the Clearing House asserted last month in defending big banks' "

JPMorgan Chase (JPM) Chief Executive Jamie Dimon has argued that big corporate customers rely heavily on the sophisticated financial services only megabanks can provide, including big loans, global cash management and deal advice.

"We bank some of the largest global multinationals in America and around the world,"

Claiming big multinationals "need" big banks might be a bit of an exaggeration, say treasurers at those large companies. Yes, a separation of banks' commercial and capital markets operations would inconvenience big businesses and raise costs, corporate treasurers and their representatives acknowledge. But for big businesses there are downsides to dealing with giant financial firms as well—and they are in no rush to defend the megabanks.

"Is it going to have a material detrimental impact on corporate America if they were broken up? I doubt that," says Jeff A. Glenzer, who oversees public policy for the

"I have not heard" the association's members voice any support for big banks nor demand a breakup, he says.

Nobody interviewed for this article advocated breaking up big banks, but corporate officials carefully expressed frustrations with the side effects of the megabanks' heft. The growing concentration of banking industry assets since the financial crisis has made dealing with the largest banks inevitable for many companies — and often requires buying a bundle of services to get the best deals on credit.

"For years now there's been a trend of banks making credit commitments as part of an overall decision on the profitability of a client. That includes a mix of credit business and fee-generating business," says Thomas C. Deas, Jr., the treasurer of chemical company

FMC, which reported revenue of $3.4 billion last year, is a "capital-intensive business" with a regular need for credit, he says. But when the company renegotiated a $1.5 billion credit facility with a group of banks last year, some lenders dropped out in what Deas calls "a self-selection process by banks who felt that the balance between credit commitment and fee-generating business was not in balance to their liking."

"There's a finite set of services that a company like FMC needs in cash management, in international banking services, in trade finance, foreign exchange, debt underwriting — all those ancillary services on which banks get additional fees," he says. "The trend in order to achieve this balance has resulted in a smaller group of more capable banks making bigger individual credit commitments."

Corporate treasurers and their representatives agree with the big banks' arguments to a point.

Big banks "have taken reputational black eyes. … Nonetheless, the largest banks still remain because of what they are able to offer," Glenzer says. Because of "the relative simplicity compared to having to deal with a large portfolio of smaller banks, they're still the banks of choice for most of corporate America."

He cites the megabanks' size and scale as advantages in helping big companies raise capital, manage risk and implement technology: "The large banks are the ones best able to justify investments into the technology that supports the other needs of large corporations. That's simply a matter of economies of scale, whether it's investing in payments technologies or information reporting technologies or supply chain finance technologies."

Deas agrees, citing the higher lending levels that companies like FMC can get from the largest banks. "Treasurers of U.S.-based multinationals rely on large banks able to provide global services and credit support around the world," he says, adding that FMC's $1.5 billion revolving credit line has commitments from most of the largest banks, including Citigroup, JPMorgan, Bank of America and Wells Fargo (WFC).

"This structure would not be supported by breaking up banks with the consequent lower statutory lending limits," Deas says.

If the big banks' commercial and investment functions were to be broken up, "it would be very inconvenient -- how many bank meetings can you cram into one week?" says one treasurer for a Fortune 100 company who was not authorized to speak on the record. "I do like the big banks. They have the most creative folks, they have the resources to do stuff that small banks cannot afford to do."

However, if they were to be broken up, "we'd manage."

Big businesses have other places to turn for financing, though each presents challenges.

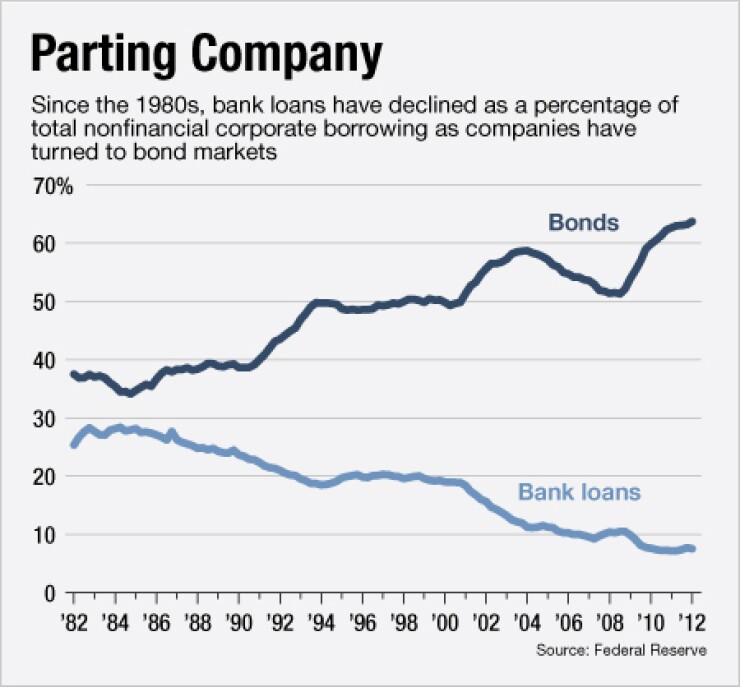

Bank loans to large companies have declined as a percentage of their total borrowing over the past few decades as corporations have turned to the bond markets, according to Federal Reserve data. But tapping the capital markets often requires going through an investment bank or a larger financial institution's investment bank unit, says Jim Simpson, a consultant at Debt Compliance Services and a former corporate financial executive at several companies.

Corporations can turn to superregional banks for commercial banking services and rely on smaller investment banks when they need capital markets and M&A services. But that alternative is impractical and overly expensive for companies that are still hurting from the economic slump, experts say.

"If a commercial bank has a very good and prominent investment banking presence, it's going to have a decided advantage," says Simpson, a former treasurer of pharmaceutical company Sandoz USA, now owned by Novartis.

As a treasurer and a chief financial officer, "the key thing for us was to make sure that everything got done efficiently at all times," Simpson says. Having smaller, specialized commercial banks that cannot offer all services, or splitting commercial and investment banking, would add costly obstacles.

"If a company has to deal with one bank for letters of credit, one bank for foreign exchange, one bank for cash management and one bank for debt, then each of these banks are going to require attention and earnings," Simpson says.

And while the biggest corporations already manage relationships with several banks at once and have more resources to do so, "even at big corporations there is pressure to reduce staff size" and manage costs, he says.

Kevin Petrasic, a partner in the global banking and payments practice firm Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker, says that for large corporations, dealing with the biggest banks "can equate to a cheaper loan, if you have a warehouse line of credit or something that has been facilitated by a larger loan."

He and others interviewed for this article were quick to praise superregional commercial banks, but said that most of those lenders cannot fully support the global cash management needs of big corporations. And then there are the changing capital requirements that affect how much lending banks can do at once.

"One of the things that the regulators are going to be looking at [is], does the lender have the scale to be able to do this type of lending, and does it have the type of network that's going to support its activities?" Petrasic, a former official at the Office of Thrift Supervision, says.

"If you have corporations that are very active internationally, they will want a banking partner that will provide the types of services, commercial and investment, that they can rely on throughout their footprint," he adds.

Dimon,

"We bank Caterpillar in like 40 countries. We can do a $20 billion bridge loan overnight for a company that's about to do a major acquisition," he told the magazine. "We move $2 trillion a day, and you can see it by account, by company."

Caterpillar (CAT), for its part, was less effusive about its relationship with JPMorgan. When asked to comment or provide an executive for this article, a spokesman for the manufacturing company replied succinctly in an email: "We have a very strong group of banks that support our global business."

Financial executives for several large companies declined, or did not respond, to requests to discuss their views of big banks. And the trade groups are lying relatively low. Neither the AFP nor the NACT have taken stances on limiting banks' size, according to Deas and Glenzer, though

"Some companies feel as if, when it comes time to needing to do something that's important that requires the support of a financial institution, their options are limited," Simpson says.

"It's a very sensitive subject," he says. "A lot of people wouldn't want to admit that there are these types of restrictions" in their bank relationships.