-

Smaller banks cannot afford to support high-density branch networks as economic challenges persist.

February 8 -

Conestoga, a Philadelphia-area bank, is hoping higher-end video setups will facilitate more complex transactions and consultations.

June 29

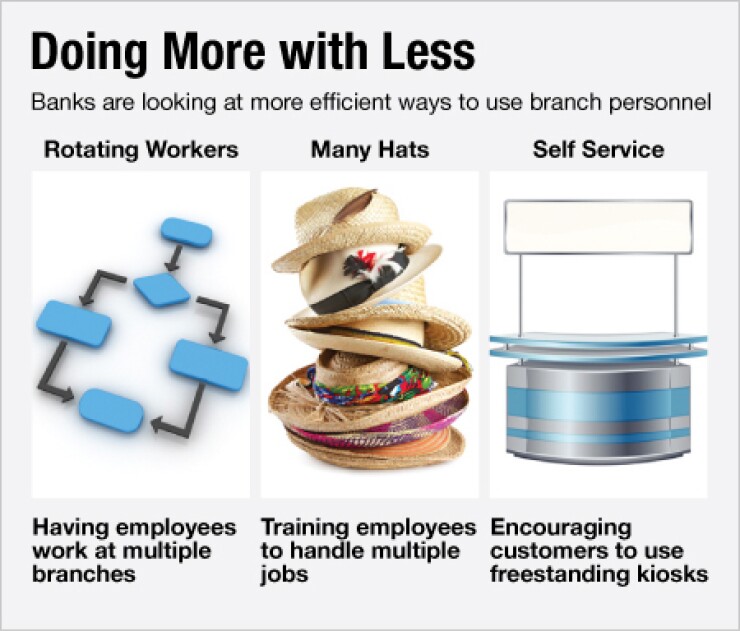

Community banks are finding ways to do more with less when it comes to staffing branches.

Banks have long sought out ways to

Every bank with at least five branches must be considering efficiency efforts, says Jamie Eads, senior project manager at Bancography. "Everyone is trying to get the most bang for their buck."

Staffing expenses often account for two-thirds of a branch's costs, Eads says. So reducing staffing, even if it involves trimming the equivalent of half of a position, can help the bottom line.

"Banks are compelled to adjust their costs based on revenues," says Judd Caplain, KPMG's advisory leader for banking and diversified financials. "That's driving a lot more innovation."

Banks collect a range of data as they study branch staffing, using the results to determine the best way to allocate resources, industry experts say. Managers must consider all sorts of items, including branch volume and transaction types, process times and the number of deposit accounts per full-time employee.

Still, smaller banks are often reluctant to follow outsiders' recommendations to consider layoffs, industry experts say.

"A lot of this is done through attrition," says Paul Schaus, president at CCG Catalyst Consulting Group. "When someone retires, the bank might move people around instead of replacing that person."

MidWestOne Bank in Iowa City is always looking at staffing and the number of transactions completed at its branches, says Sue Evans, its chief operating officer. When a position becomes vacant, the $1.8 billion-asset bank considers whether the post is needed and if it could be filled on a part-time basis.

MidWestOne, a unit of MidWestOne Financial Group, sometimes opts to hold off on filling a post as it decides "if we need someone and, many times, we just never fill the role," Evans says. "Our employees step up and realize that it is a position that didn't need to be filled. … That's part of our culture."

MidWestOne routinely hires college students, Evans says. Banks often hire college students or other part-timers to work a few hours a day at peak times, says Lynn David, CEO of Community Bank Consulting Services.

Banks can cut costs because they don't have to offer full benefits packages to part-time employees. Still, the tactic has disadvantages, including the potential for high turnover and scheduling conflicts.

"You will have more turnover, especially if you are using college students," David says. "But these employees are great because they are bright and computer literate."

MidWestOne uses college students for more than just peak hours, Evans says. To address concerns about scheduling, the bank recently increased its use of floating employees. A floater works at more than one branch during the day, covering for employees who have taken time off or called in sick.

The role has also created opportunities for employees who want to move up at the company, Evans says. It allows employees to gain more experience through exposure to new situations and working with different managers.

The use of floating tellers and new accounts personnel has become more popular, serving as an easy solution "to optimize the utilization of your staff," David says.

MidWestOne's floating employees have evolved from serving as tellers to the role of "universal banker," Evans says.

More community banks have shown an interest in moving to a universal agent model rather than having distinct tellers, new accounts personnel and customer service representatives, industry experts say. It lets a bank "consolidate some of those roles," says Marcia Wakeman, a partner in Capco's banking group.

Technology such as cash recyclers in teller lines has also made this strategy more practical, experts say. Universal agents are able to process transactions, such as deposits, at peak times. They are also capable of opening accounts or addressing customer concerns.

More banks are spending time training employees to become universal agents with more of a focus on selling products to customers, Caplain says.

"Although the banks and consumers aren't there yet, banks would like to use branches as a store," he says.

There are potential problems to the universal agent model, some industry experts say. Customers can become irritated if they believe a bank's employees are spending too much time pitching products, particularly those that do not fit their needs, Caplain says.

Additionally, some tension can arise when banks cross train workers, experts say. Not all employees have the skills or personality to handle customer service or sell products. And some employees may be reluctant to complete a teller's duties.

More community banks are also starting to resurrect self-service kiosks that act as an expanded ATM, though this trend has been slower to catch on, Wakeman says. Banks are also considering personal teller machines that let consumers chat with customer service representatives off-site, which can save money on personnel and real estate costs.

Self-service kiosks appeal to younger customers who are more comfortable with technology, and they give customers another option, Wakeman says. Before implementing such a change, banks must consider several factors, such as potential security risks, physical constraints and customer benefits.

"It will still take many years for the kiosks" to increase in popularity, Wakeman says. Banks must ask themselves, "What do you really do at the kiosks, why would I use a kiosk and when does it become different than an ATM?" she says.

Smaller banks often position themselves as having better customer service than larger competitors. Because of this, a "kiosk may not be a great thing," Caplain says. "The local community bank usually wants to talk to the customer."

Before rolling out extensive changes, banks should slowly pilot ideas, starting with a few branches. From there a bank can decide to expand or cancel the changes, Eads says.

To measure overall customer satisfaction, banks should constantly monitor social media for complaints, while also soliciting feedback through surveys and focus groups, Wakeman says.

"Banks should be looking at certain markets and demographics" when making changes, she says.

"It should not be a one-size-fits-all approach."