On June 5, 2013, Barry Silbert, the 36-year-old founder and CEO of SecondMarket, called an all-hands meeting to announce a new direction for his brokerage firm.

Since its founding in 2005, SecondMarket had earned a reputation for trading exotic assets. The news that day would only reinforce it — and would give even some of SecondMarket's employees cause for concern.

A former investment banker, Silbert had built a successful company by making it possible for hapless investors to unload illiquid paper. Auction-rate securities were one of several asset classes for which he had almost single-handedly made a market amid the chaos of the financial crisis. (An

-

It is outside the realm of possibility for bitcoin's blockchain to serve any useful purpose for the intermediaries it was designed to replace.

February 4 -

Blockstream, a tech startup that employs several core developers of the bitcoin protocol, has raised $55 million in venture capital to develop its sidechain technology and expand its global operations.

February 3 -

Bank of America has nearly three dozen patents pending related to blockchains. More banks are expected to seek patents as the technology associated with cryptocurrencies creeps closer to widespread use.

February 1 -

Federal and state banking regulators are still struggling with how to come to grips with banks whose clients are heavily involved in digital currencies like bitcoin and that may be curbing interest from many in the financial industry.

January 29 -

PricewaterhouseCoopers has partnered with the blockchain technology company Blockstream to bring distributed-ledger and smart-contract technology to its clients.

January 29 -

Digital Asset Holdings, the blockchain technology startup led by Wall Street veteran Blythe Masters, has raised more than $50 million in funding and expanded its board, the company said Thursday.

January 21

Though auction-rate securities had been his trading desk's most profitable asset for a while, he knew that wouldn’t last. No new ones had been issued in years, and the secondary market for them was beginning to dry up. Silbert needed to find a new asset class to trade in.

The company, Silbert told his staff, was going to open a private fund for accredited investors that would invest solely in bitcoin. The move would effectively put SecondMarket's future at the mercy of a volatile digital currency that most people thought was a passing fad, a mere tool for peddling drugs online, or a Ponzi scheme. Nobody even knew the real identity of bitcoin's creator, who used the handle Satoshi Nakamoto. "Highly unorthodox," the financial blogger Felix Salmon

But Silbert had become a true believer. "Barry called bitcoin 'the biggest opportunity of my career,' " recalled Michael Moro, the director of SecondMarket's trading desk at the time.

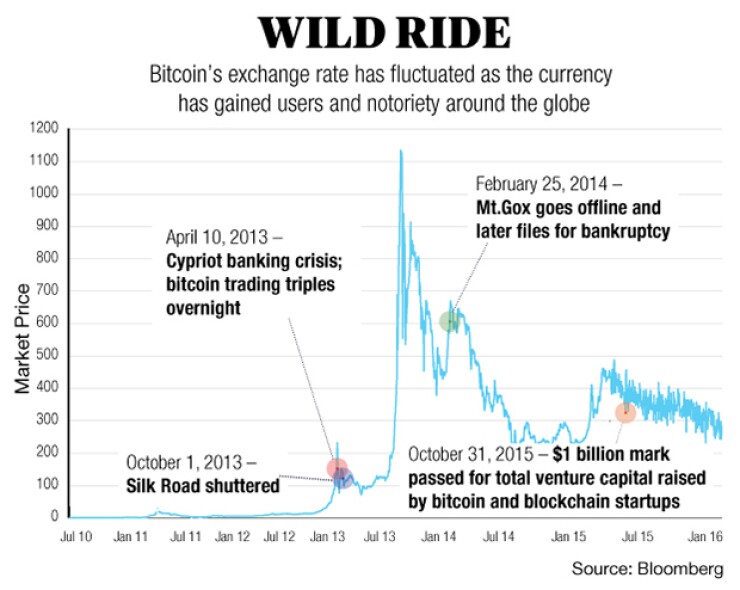

Nearly three years later, Silbert's bet doesn't sound quite so crazy anymore. Bitcoin's market capitalization has grown nearly sevenfold over that period to $6.8 billion. Investors have poured more than a billion dollars of venture capital into startups that are experimenting with bitcoin and the technology underlying it, an innovation called the blockchain. And while naysayers still abound, big Wall Street firms are more curious than skeptical. Even national governments and central banks are taking a look.

Meanwhile, Silbert has gone all-in, and in doing so positioned himself at the heart of the bitcoin and blockchain industry. Ask anybody in the world of bitcoin today who is the best-connected member of the community, and odds are they will direct you to this boyish entrepreneur, a man who may be uniquely suited to bridge the gap between rebel entrepreneurs and mainstream financial institutions. In a fintech space that has seen more than its share of blowups, meltdowns, flameouts and criminal charges — and in which serious differences of opinion persist as to whether

"He definitely approaches it from a much more practical, pragmatic angle" than do the hard-line cryptolibertarians, said Alan Lane, the president and CEO of Silvergate Bank in La Jolla, Calif., which provides banking services to about a dozen bitcoin startups. "He has been a really good bridge for a lot of the younger techie idea folks — trying to figure out how to fit them into the mainstream without losing what they're bringing."

The arc of Silbert's career — from a trader of distressed paper to a prolific investor in one of the most experimental corners of fintech — parallels a broader shift in the story of financial services. In the last few years, as the industry has recovered from the crisis, banks have turned their attention from cleaning up yesterday's messes to fending off tomorrow's challengers.

While working with banks and established investors is unavoidable, "the real innovation — the paradigm shift, the new way of doing things — is not going to be driven by the incumbents," Silbert said. "It's going to happen outside the existing financial system. And ultimately those ideas will be

Among the first to recognize the interest that bitcoin and its underlying technology would hold for Wall Street, Silbert has found himself testifying before the New York State Department of Financial Services and coaching asset managers who manage tens of billions of dollars. Last year his fund, the Bitcoin Investment Trust, grew until it held 140,000 bitcoins — about 1% of all bitcoins in existence — and then Silbert took it public on the OTCQX market, making it the first publicly traded fund of its kind.

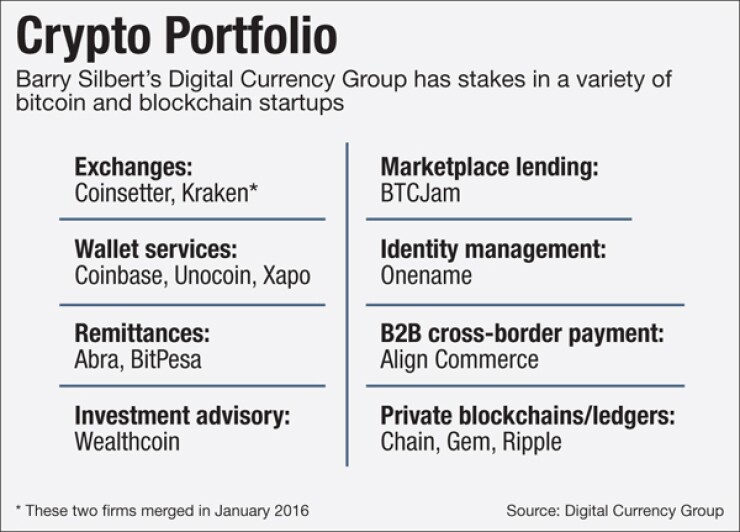

Alongside this he built a profitable bitcoin trading desk to serve institutions and high-net-worth individuals. The final piece fell into place last October, when he split off these businesses as wholly owned subsidiaries of Digital Currency Group, a new conglomerate, and sold the rest of SecondMarket to Nasdaq. What were once Silbert's personal stakes in dozens of digital-currency startups now belong to DCG's portfolio of early-stage investments. He intends for DCG to function as an index on the entire market, becoming "the Berkshire Hathaway of bitcoin."

To the chagrin of idealistic techie types, Silbert is not shy about appealing to the profit motive, and often touts the potential for bitcoin's price to rise. Yet he is sincerely convinced that bitcoin is not merely a good investment but a good thing for the world.

"I haven't seen Barry so passionate about something since he first started the company," said his wife, Lori Silbert. "He thinks bitcoin, and even more so digital currency, could be life-changing for our daughter."

BORN TO TRADE

Silbert, who grew up in Gaithersburg, Md., has been in training for his career from childhood. At age thirteen he was selling baseball cards — learning then that some things have monetary value simply because enough people agree they do. He invested his bar mitzvah money in stocks.

As a high school junior, he landed a part-time job at a Washington brokerage firm. Sensing his interest in the markets, the portfolio managers and traders there encouraged him to take the six-hour, 250-question General Securities Representative Exam, which would qualify him to be a stockbroker. If he passed, he would be granted a Series 7, or General Securities license, allowing him to buy and sell stocks, options and all other types of securities. Silbert took the test at age 17, becoming one of the youngest people ever to pass.

After graduating in finance from Emory University in 1998, he moved to New York and began working as an analyst at Houlihan Lokey Howard & Zukin, a boutique investment bank. In his second year, he was adopted into the financial restructuring division — with the dot-com bubble just about to burst.

The years 2000 to 2003 were "the boom years of the bust," fat years for the restructuring division of Houlihan Lokey, Silbert said. He was promoted from analyst to associate, and worked on some of the decade's headlining bankruptcies, including Enron and WorldCom. But then the pool of clients began to dry up, even as competition for their business grew fiercer. And Silbert had become bored with the work. He wanted a change.

Striking out on his own, he opened Restricted Stock Partners — later to be renamed SecondMarket. The simple phone brokerage aimed to make a market for investors with assets they were having trouble unloading through traditional means. His first target was restricted stock in public companies, sales of which had to be kept private in accordance with Securities and Exchange Commission regulations. It was a huge opportunity. In 2004, the market in restricted securities was worth more than $1.2 trillion — greater than the GDP of Australia or Mexico.

Not long after leaving Houlihan Lokey, Silbert had run his business plan by Jeff Werbalowsky, the investment bank's co-CEO. He asked whether the firm would like to invest in Restricted Stock Partners. Werbalowsky considered the business plan risky and passed, but was struck by the young former associate's entrepreneurial zeal. "He took all of my thoughts and suggestions and critiques in stride, and answered them or said, 'We'll surmount them,' " Werbalowsky said.

Silbert financed the venture with $50,000 of his own money and $350,000 from angel investors. "It was five of us, five telephones and an Excel spreadsheet," he said. "That was it. That was our marketplace."

The business grew rapidly, surviving the death of Silbert's business partner, Brad Monks, from cancer in 2007, and launching an electronic trading platform.

One of the early investors was Lawrence Lenihan, managing director of FirstMark Capital, who now sits on DCG's board of directors and investment committee. His firm put $3.8 million into Silbert's company, valuing it at more than $15 million. Lenihan's first impression of Silbert was that "he looked like he was about 12 years old." But Lenihan said he never doubted the younger man's intelligence or ability.

'THE REALLY TOXIC STUFF'

As the financial crisis deepened, SecondMarket expanded into new asset classes: auction-rate securities, bankruptcy claims, mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations — "the really toxic stuff," as Silbert puts it. It was a tough time for the established players, but for SecondMarket it was a bonanza. Trillions of dollars of assets had turned illiquid during the meltdown. SecondMarket brought buyers and sellers together and charged a straightforward commission, between 3% and 5%, on the value of what was being traded.

"The world was falling apart at that time," said Jeremy Smith, who was SecondMarket's head of strategy then. "All of these assets were freezing up, and we said, 'Hey, we're a marketplace for creating liquidity.' So every time an asset froze up, we created a marketplace for it."

Hearing what her husband intended to do for auction-rate securities, Lori Silbert asked, "Do you even know what they are?"

"Nope," Silbert replied. "But I'm going to figure it out."

By early May 2008, about $3.5 million of auction-rate securities were being traded over his company's platform every day.

At the same time, SecondMarket had begun trading Facebook stock — nearly $50 million of it — on behalf of employees who didn't want to wait for the IPO. That was how Silbert got into buying and selling stock in private companies, making a market for early investors and employee shareholders who wanted to liquidate their stake in hot startups. Facebook was a popular one, as was the video game maker Zynga. In the world of startups, early employees often take a deep pay cut in exchange for a stake in the company. There had never been an organized market for turning these shares into cash, but now, suddenly, there was.

"Barry has an unbelievable, almost uncanny ability to identify markets before they develop," Lenihan said. Indeed, by early 2011, SecondMarket had brokered sales of private-company stock — including that of tech darlings like Twitter and LinkedIn — totaling more than $500 million. It was SecondMarket's platform for these sales — known as liquidity events — that eventually attracted Nasdaq's interest.

Before the year was out, SecondMarket was flush with $30 million of new capital from two fundraising rounds, the second of which valued the company at $200 million. It was now the world's largest centralized exchange for a wide variety of illiquid assets.

But then SecondMarket went through a lean season. As the financial sector recovered from panic and the national economy began dragging itself slowly out of the doldrums of recession, secondary trading in many of the exotic financial products that had fueled SecondMarket's success began drying up. Meanwhile, the mania for over-the-counter sales of private-company stock was temporarily dwindling. SecondMarket was forced to close its offices in Israel and Hong Kong and move its headquarters out of the financial district. The company's New York workforce shrank by nearly two-thirds.

CATCHING THE BUG

Silbert began buying bitcoins in the summer of 2012. Initially he kept quiet about his stake in the digital currency, worried it would damage his reputation if word got around. Even his wife was in the dark at first. But gradually he became convinced that its technology could change the world and, consequently, that it was a spectacular long-term investment.

At first, the process of acquiring the digital currency — going through an unlicensed online exchange whose office was in Japan — made him nervous. "I would wire like $5,000 to Mt. Gox, be scared shitless that I was never going to see it again," he said.

Once he'd bought his first batch of bitcoins, though, he didn't wait long to buy more. He had caught the bug. Over the next two and a half months, with the price of bitcoin slowly climbing from $5 to $10, he invested about $200,000 in the digital currency.

Initially bitcoin was simply his hedge against what he sees as a dangerously overleveraged world. After spending his early twenties helping to liquidate failed companies, he then built SecondMarket on the bones of Wall Street's failures, its toxic assets, bad debt repackaged as good debt, on other men's missed opportunities. By the time he heard about bitcoin, he felt a little like Noah in his ark, looking out on a world awash in debt.

"When you have a world that is printing money, the concept of a decentralized, non-government-controlled, non-company-controlled currency that has a finite supply had a certain amount of appeal to me," Silbert said. "I didn't fully appreciate the whole technical aspect [of bitcoin] at first. But economically it just kind of made sense."

At one time he had been something of a gold bug, but no longer. Too many governments were stockpiling gold as a backstop to their economies. Gold had history on its side, but eventually Silbert came to see bitcoin as a far more secure investment than precious metals.

"On a probability, risk-adjusted basis, if I'm going to make a bet on what people want to own if the shit hits the fan, I'm going to want to make a bet on something that's not being held by all the central governments whose fan is being hit with the shit," he said.

While others were debating whether digital currency met the textbook definition of money, Silbert saw that bitcoin was a triple threat to established markets, because it could function as a store of value, like gold; as a method of payment for online commerce, like credit cards or PayPal; and as a global transaction network, like Western Union or MoneyGram. There are about $7 trillion worth of gold in the world today. E-commerce is a $1.6 trillion industry. According to the World Bank, a total of $583 billion in remittances flowed to nations around the world in 2014, and an estimated $600 billion in 2015. What if bitcoin were to claim even a small percentage of any of these markets, never mind all three?

"If I'm going to make an investment in a high-risk opportunity like bitcoin, I'm only going to do it if it's going to move the needle for me," Silbert said of his early investment in the digital currency. The value of bitcoin relative to the dollar, he thought, had the potential to increase by 50 or even 100 times. "If it does that," he told himself, "I will always look back on this time and say, 'Why were you such a pussy? You had the money, why didn't you do it?' "

THE BIG PIVOT

In the summer of 2013, the entire staff of SecondMarket, more than 50 employees, gathered in the rec space on the top floor of their building in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. A kind of loft with hardwood floors, it was kept stocked with snacks and drinks and served as the event space for twice-monthly "town halls" — loosely structured meetings at which employees were encouraged to speak up and ask questions.

Most of them knew next to nothing about bitcoin. Their CEO, dressed summer casual, his short blond hair combed forward in a youthful style, gave a PowerPoint presentation. He had briefed his senior leadership team ahead of time, but he knew what he was about to say would come as a surprise to the rest of his staff. He introduced the concept of bitcoin, giving an overview of its innovative features — its immunity to counterfeiting and double spending — before taking a stab at evaluating its potential for their business. He compared it to gold, to major fiat currencies.

"Look at the size of those markets," Silbert said. If bitcoin could capture just a fraction of that wealth, its value would skyrocket. The fund he was creating would enable investors to get in on the action without taking any of the risks or hassles of sourcing, storing and securing the bitcoins for themselves.

But Silbert also gave a few words of caution. There was no guarantee that bitcoin would survive, and that made his new direction for the company a risky one. "In the end, it's too early to tell," he told them. Despite the potential, "there is a real chance that it will go to zero and this was a passing fad." Even while laying out his strategy, he wanted to present the facts as soberly as possible. Throughout the presentation, however, Silbert made no attempt to hide his enthusiasm.

And he had another surprise. To familiarize his staff with the digital currency, he was going to give each of them, out of his personal hoard, two bitcoins — one to save and one to spend. At that point, most of them had heard Silbert talk about bitcoin, but very few understood what it was. "I've always thought that until you actually receive it or spend it or buy something with it, you don't fully appreciate how powerful the concept of bitcoin is," Silbert said. "So what I figured was, one, I want my employees to understand what I've been excited about it firsthand, and two, I wanted them to have some skin in the game." By spending one of their coins, they would experience the bitcoin technology, and by holding one they would enjoy the potential upside of bitcoin the speculative investment.

If you could have measured employees' attitudes as they filed out of the meeting, they would have presented as a bell curve — a small number of people totally on board with their CEO's plan, a small group of skeptics at the other end, and the majority in between, excited by the prospects but still harboring various doubts.

Silbert wasn't just planning to provide a market for bitcoin trading, as he had done with other alternative investments; he was creating a bitcoin fund. If investors didn't buy in, he would be in trouble. SecondMarket could survive, because it was doing brisk business arranging stock sales for private companies, but he would have to lay off most of his traders. The secondary market for auction-rate securities was becoming a desert, and pretty soon, if his trading team wasn't trading bitcoin — mainly, at first, sourcing it for investors in the new fund — it wouldn't have much of anything to trade. He'd also have to fire legal and technical staff who were focused on the intricacies of bitcoin. A failure of the BIT would mean cuts across the board.

He was also putting a lot of company money on the line. In preparation for launching the fund, SecondMarket bought up $3 million worth of bitcoins at between $105 and $110 a coin. Silbert's plan was to kick-start the fund with about two-thirds of the company stash; the remaining money would be kept on SecondMarket's balance sheet. The trust would provide same-day settlement of orders. One trader later explained it this way: "You make an investment, we go out and source the bitcoins, and you're an investor in the fund that day."

As 2014 drew to a close, DCG, which had yet to launch publicly, was sitting pretty despite a brutal year for the price of bitcoin. Its total assets included more than $13 million in cash plus 40,521 bitcoins, an amount then worth $12.9 million — and now, at time of writing, worth $18.3 million. Genesis Trading, which would become a subsidiary of DCG, was perhaps the leading digital currency trading desk for institutional investors and high-net-worth individuals, with a trading volume of more than $300 million since its inception and 2014 revenue of $12.6 million. The Bitcoin Investment Trust would soon become the first publicly traded bitcoin fund. It, too, was generating revenue. The company's long-term debt, in keeping with Silbert's business philosophy, was zero.

"If back in 2006 Barry had said, 'You know what, I want to manage my own hedge fund and identify and invest in asset classes before anyone else,' he'd probably be a billionaire right now," Smith said. "He has this vision where he can put together the whole long-term picture of how certain things will play out."

BITCOIN VS. 'BLOCKCHAIN'

Bitcoin has attained a level of popularity and public awareness its early adopters could scarcely dream of. But its ultimate success is far from assured. It continues to be subject to wild price swings, and critics say the extreme hoarding of some bitcoiners prevents the currency from functioning effectively as a medium of exchange.

No less a figure than Warren Buffett is on record as calling bitcoin "a mirage." While the sage of Omaha acknowledged that its payments network holds promise as a faster way of sending money around the world, he said in 2014 that "the idea that it has intrinsic value is a joke."

Last November, Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, raised another worry, telling an audience that governments would squash bitcoin before it could become a true competitor to the dollar and the euro. "Virtual currency, where it's called a bitcoin versus a U.S. dollar, that's going to be stopped. No government will ever support a virtual currency that goes around borders and doesn't have the same controls."

More recently, skeptics have been giving bitcoin a sort of backhanded compliment, acknowledging the power of the blockchain but dismissing the currency as a distraction and its early adopters as kooks. Bitcoin, according to the latest conventional wisdom, is at best something banks can learn and take ideas from — it is, after all, open source — but isn't suitable for them to use.

"Satoshi, to his credit, wasn't trying to design a system with banks in mind — in fact, just the opposite," said Tim Swanson, the director of market research for R3CEV, a software startup that has put together a global consortium of banks focused on applying blockchain technology to financial markets. Wells Fargo, BNP Paribas, Santander, JPMorgan and many of the world's other big banks have signed on.

Swanson points out that certain features of bitcoin as currently designed — such as a low limit on the number of transactions that can be processed each second — make it impractical for use by financial institutions. Other features, such as the ability to transact pseudonymously, are unnecessary for banks or even run counter to their compliance needs.

"Bitcoin, as it exists today, does not solve a problem that large, regulated institutions have," Swanson said.

Rather than being excited about its potential as a payment system or its possibilities as a store of value, rather than beginning to trade bitcoin as a kind of emerging-market currency — scenarios Silbert envisioned early on — financial institutions have seized on the concept of an automated shared ledger, the innovative method of asset transfer and record-keeping that undergirds bitcoin. "I would not be surprised to see over the next 10 years a radical change in business processes," said Vivian Maese, a partner in the New York office of the law firm Latham & Watkins.

Swanson estimates that at large financial institutions there are now about 500 people, all told, working on what he calls "noncryptocurrency distributed ledgers." Meanwhile, in the fourth quarter of 2015, "venture capital funding in cryptocurrency startups has fallen off a cliff."

Silbert admits that he "was right but for the wrong reasons" when he predicted that Wall Street would take an interest in bitcoin's technology. Yet he remains steadfast in the opinion that the industry will come around to embracing the currency. Banks' experiments with private blockchains will prove to be nothing more than "a gateway drug, ultimately, to them using the bitcoin blockchain," he said, "and then also to holding bitcoins, trading bitcoins, speculating in bitcoins."

There's a reason Silbert is so sure of this: Even though big banks might be leery of adopting bitcoin proper, whether because of compliance costs or other reasons, Silbert said, "the individuals who work at those places, they all own bitcoin."

Still, he appears nowadays to be quietly hedging his bets. In September, DCG contributed to the $30 million Series A funding round for Chain, a onetime bitcoin startup that pivoted to focus on private blockchains and developed one for Nasdaq. In January, DCG joined in the $7.1 million Series A of another blockchain-as-a-service startup called Gem that, like Chain, has shifted its emphasis away from bitcoin, believing the needs of enterprise clients require purpose-built solutions.

THE ROAD AHEAD

By the end of last year, DCG held stakes in 60 startups across 20 countries. Among them were industry leaders Coinbase, Xapo, Ripple and Chain.

"We have now a large percentage of the earth covered from a bitcoin/digital currency infrastructure perspective," Silbert said. "We've invested in exchanges in China, in Japan, in India, in the Philippines, in Mexico, in Argentina. That gives us really fantastic insight into what's happening around the world — where is there adoption, what are governments doing, what are banks doing. … We have all the data."

One year earlier, its portfolio contained about 50 startups and was worth an estimated $11 million, by DCG's own accounting. Since DCG — and Silbert himself in his earlier investments — looks to get in at the seed stage, providing $150,000 to $250,000 in exchange for 2% to 5% of each startup, back-of-the-envelope math would suggest that the total enterprise value of those companies in December 2014 was between $220 million and $550 million. No doubt the value has grown significantly since.

When Silbert began to hunt for investors for DCG one year ago, his goal was to raise $25 million. Though he won't confirm whether the company raised that much, the quality of the investors who signed on — MasterCard, Bain Capital Ventures, New York Life, CIBC, RRE Ventures and other heavy hitters — is impressive.

DCG continues to average one or two new investments each month, and its CEO has given careful thought to the types of startups he wants to add to this burgeoning portfolio. Prior to 2015, his thesis was that digital currencies were only as strong as their core infrastructure, and so he invested mainly in companies that were building that payments infrastructure. His new thesis, since early 2015, has been that most of the essential infrastructure of the bitcoin ecosystem is now in place, at least in the United States. What is needed now is to fund the "killer apps" that will drive mainstream adoption of digital currency. Among these are remittance solutions, payroll and lending services for the unbanked, smart contracts, distributed asset records, bank-to-bank settlement services, and blockchain-powered microtransactions for the Internet of Things.

By late October 2015, when SecondMarket was sold to Nasdaq, the bitcoin industry as a whole had raised more than $900 million of startup capital. Between them, the companies in DCG's portfolio had raised some 70% of that total. DCG's own funding round helped push the total beyond $1 billion.

Having built a company at the epicenter of bitcoin, Silbert is now making use of its position to strengthen the industry as a whole. From interviews and company documents, it's clear that he sees DCG's network of startups, investors, advisers, experts and corporate partners as an interconnected web, an extended family of human and financial capital with rich opportunities for mutual benefit. DCG recently hired a head of community to facilitate these relationships. In addition, Silbert said, "We're rolling out tools for all of the executives of our companies to use." One of these is an internal wiki, a "repository of content, resources and expertise" for all of DCG's portfolio companies. DCG also intends to organize seminars, workshops and executive summits for the entrepreneurs in its network. In early January, DCG closed a deal to buy CoinDesk, the most popular of the numerous news outlets that have sprung up to cover the bitcoin industry.

One idea for a future business is to hire industry veterans to consult for Fortune 100 clients, launching a kind of McKinsey for bitcoin. Another is to open a bank that would use the blockchain as its backbone to provide payroll and peer-to-peer lending services. Neither venture is certain, but they reflect the scope of his ambitions. "I would love to have the investing success that Berkshire Hathaway has had," he said, "but I'd love more to have a meaningful impact on society and on our financial system in particular."

The Bitcoin Investment Trust's net asset value grew 32.67% last year, to $60 million, and Silbert said he has "never been more bullish on bitcoin as a speculative investment." DCG is widely expected to file an S-1 soon in order to list the fund on Nasdaq or the New York Stock Exchange. In the longer term, Silbert plans to take DCG itself public.

Within five years, he predicts, bitcoin either "will be a failed experiment, and something else will have taken its place, or it will be eating the world."

Brian Patrick Eha is a freelance writer in New York whose work has been published by The New Yorker, Entrepreneur and others. This article is adapted from his forthcoming book about bitcoin.