Cambridge Savings Bank hopes customers who walk into its new Boston branch will notice that something is different.

The $3.7 billion-asset bank installed an interactive teller machine, a device that looks like an ATM with videoconferencing capabilities, at the branch. It lets customers talk with a banker about their accounts, just as they would in a traditional teller line. The machine also allows Cambridge to offer extended hours, 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

“It is a great way for customers to come in after work," said Wayne Patenaude, the $3.7 billion-asset bank's president and CEO. "If they need something answered right away, we can make that happen. ... We think this kind of technology is the wave of the future.”

Cambridge is one of several community banks experimenting with technology that has been around for a few years. Those that are adopting the machines are looking to provide convenience for customers in hopes of securing a competitive advantage, industry experts said.

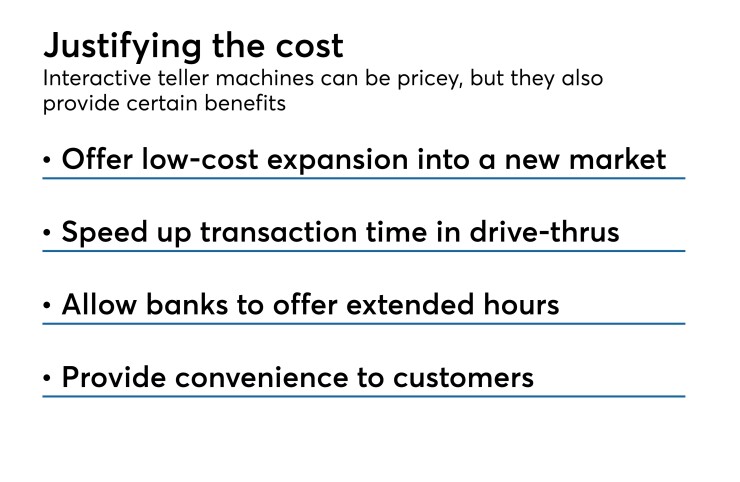

The machines could also help banks automate more transactions and reduce overhead tied to physical branches, though the ultimate bottom-line benefits of investing in the expensive technology remain unclear.

Calculating a return on investment is “where a lot of folks are struggling,” said Kevin Tweddle, head of the Independent Community Bankers of America’s innovation and financial technology group. “Yes, you’ll save on personnel cost in the long run, but it’s a pretty significant" upfront investment.

Interactive teller machines require a bigger investment than traditional ATMs, said Chris King, vice president of sales in the community financial institutions division of the manufacturer NCR. NCR declined to disclose pricing.

While a typical machine can cost $75,000, the underlying software could run up to $500,000, said Steven Reider, president of Bancography. As a result, banks should consider installing multiple units to make the most of the fixed costs.

Ryan Rackley, a senior director with Cornerstone Advisors, a consulting firm in Scottsdale, Ariz., said he has yet to see the new technology reduce a bank's expenses, since institutions still have to employ tellers in call centers to man the machines. He estimated that only 5% of all banks have invested in interactive teller machines.

Though a number of big banks have embraced the machines, Reider said community banks have been more hesitant — for good reason.

“Customers are sold on personalized service," Reider said. "To come into a branch and not have the opportunity to work directly with an employee, face-to-face, is probably contradictory to the promise of the branch to begin with.”

The key to success will involve finding a balance between personalized service and technology, said Carter Campbell, president of National Property Concepts, which offers consulting services tied to branch design. Some community banks are testing interactive teller machines, rather than jumping in headfirst.

Cambridge Savings has three machines in its Boston-area branches. Patenaude said the bank is taking its time to learn more about the technology before investing in a larger fleet.

“We're pleased right now with the three we have and we will watch how they develop,” he said.

Other community banks are further along adopting the technology.

Tower Community Bank in Jasper, Tenn., has 13 machines with two more on the way, said Lorie Heller, the bank’s chief experience officer. Heller said the $167 million-asset bank first learned about interactive teller machines in 2015 at a technology seminar in Las Vegas. By October 2016, Tower Community had deployed 12 ITMs in branches and as stand-alone, remote locations.

Heller said that about 38% of all bank transactions are now done through the machine. In one instance, Tower replaced a branch with an interactive teller machine; it is the third-most used machine in the bank's network.

“We still serve people in that community because of the" machines, Heller said.

It was important to the bank that no employees be displaced by the tech effort. Instead of firing people, Tower chose not to fill positions as they became vacant.

“We were not going to get acceptance with the technology from customers or employees if it was prefaced by getting rid of 10" employees, Heller said.

While Tower has yet to break even on its investment, Heller said the machines offer added convenience and a way to attract and retain clients.

“How do you measure that?" Heller said. "That’s pretty important, and happened almost immediately."

Some banks have had more trouble making the switch, industry observers said.

A common mistake is placing a machine next to a teller line, Rackley said. Banks should also create a marketing and communication plan tied to the investment. And it is important to educate employees and customers on how to use the machines.

There have been times where a machine "just showed up one day," Rackley said. "No one knows how to use it, so they just don’t."

Trustmark in Jackson, Miss., has tested and adjusted its strategy for interactive teller machines.

In early 2017 Trustmark put one of its machines next to a teller line and another in a drive-through lane, said Joe Gibbs, the $13.8 billion-asset company's director of customer experience. While the drive-through machine met expectations, customers largely ignored the one near the teller line.

“It’s hard to change behavior,” Gibbs said. Customers "see the tellers they always use and continue to migrate and use those tellers. They didn’t just adopt the ITM.”

Trustmark will continue to slowly add machines, Gibbs said. For now, the company is studying customer behavior and the best way to deploy the machines. Trustmark added one interactive teller machine in a hospital where many employees had no time to go to a branch.

“We're starting to see repeat customers coming back to the ITMs," Gibbs said.

The machines should eventually become a more pivotal part of community banks' branch strategy, particularly for those looking for a low-cost way to enter a new market, said Mark Charette, CEO of Solidus, a Connecticut firm that specializes in branch transformation projects.

Charette compared the machines to airport kiosks that allow travelers to check in without going to the counter. When the first kiosks appeared, the airlines had employees on the floor showing customers how to use them.

"I think we're at the early stages of introducing self service in banking to a new generation of people," Charette said.

Rackley compared the interactive teller movement to the first ATMs in the 1980s.

“This is the 2018 version of that same discussion,” Rackley said.

“The return on investment is still not totally proven, but there are a number of factors where it just makes sense," Rackley added. "It’s going to take time for best practices to emerge and for customers to gain acceptance of it. We have early adopters using it as a differentiator and we have a much larger client base in that watch-and-learn" stage.