WASHINGTON — While lawmakers consider whether to require systemically important firms to draft their own advance resolution plans — dubbed "living wills" — the utility of such outlines is already a matter of fierce debate.

Under legislation to create a regulatory regime for systemic firms, companies would have to submit regular wind-down plans to the government, giving regulators a road map of how they should be taken apart in a crisis without harming the financial system.

But several observers question whether such a guide would really be followed if another crisis hits.

"The exercise of figuring out where your risks are, and how you might unwind those risks, is probably a healthy exercise at the end of the day," said John Douglas, a partner at Davis Polk & Wardwell and a former general counsel at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. "Whether it actually translates into giving you a meaningful head start if you actually have to unwind it, I think that's debatable."

The bill by House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank would require large financial firms to give the Federal Reserve Board — the proposed systemic-risk regulator — periodic plans "for rapid and orderly resolution in the event of severe financial distress."

The goal is for the firms and the government to be ready so that a resolution is more orderly than the improvised response to the collapses of last fall, such as the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. The plans would have to include information on a company's financial relationships with other sizable firms.

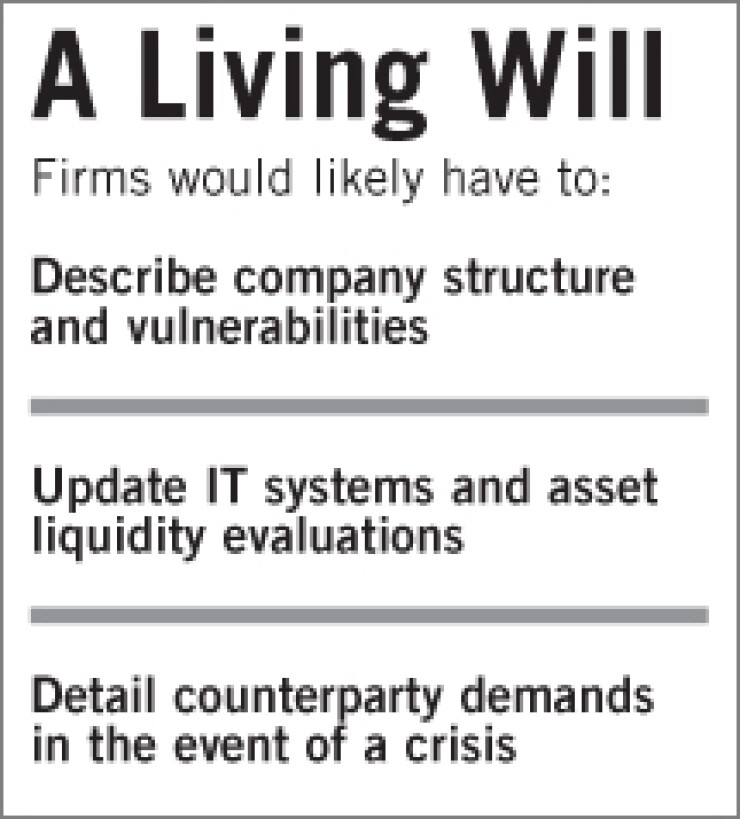

Though the bill contains no more detail, some experts said plans would likely need to contain a clear description of a company's organization, including how affiliates are connected to one another; a pledge to regularly update information technology systems, which would be a key tool in a resolution scenario; and details on how cross-border affiliates would be resolved.

"There would need to be a clear plan of counterparty demands so that the regulator knows what funds might leave under stressed situations," said Karen Shaw Petrou, the managing partner at Federal Financial Analytics Inc.

"If it does what it should, then" the living will "could not be thrown out in a crisis, because it would ease crisis resolution, and hopefully reduce resolution costs."

Robert Hartheimer, a former director of the FDIC's division of resolutions, said one key component of a resolution plan could be outlining how a firm's failure would affect various stakeholders and how to ease the impact on them.

For example, he said, an institution specializing in consumer products, such as annuities, would need to assess the impact of a failure on its consumers, unlike a company whose customers are mostly other financial institutions.

"In the case of AIG, it was clearly a concern institutionally that if they were not able to be a solvent counterparty to their credit default swaps, then we would have seen the bankruptcy of a dozen or so large financial institutions," Hartheimer said.

David Nason, a former assistant Treasury secretary for financial institutions in the Bush administration and now a managing director at Promontory Financial Group, compared the process to "stress-testing in the extreme."

He said firms would need to evaluate which assets could be sold off quickly — and are not committed to outside parties — to optimize liquidity.

"The exercise is designed essentially to run yourself through a mock bankruptcy," Nason said.

Nason added that firms would likely assign experts from different areas within the company to collaborate on the contingency plan.

If a company made a serious attempt to model its wind-down, the final product "could be huge," he said.

"The documentation that goes into that [exercise] has got to be binders and binders full of assumptions regarding asset values, funding plans and counterparty risk. It's an incredibly complex exercise, and it's going to be full of educated guesses," he said.

But despite the plans being required in the legislation, the bill also states the government is under no binding obligation to follow a living will during a resolution.

Observers said a company-manufactured resolution plan on file could run the risk of being outdated and obsolete if it differed from a firm's real-time problems, and at the least would have to be updated routinely to have legitimacy.

"It just seems to me that it's going to cause a lot of work and have very limited practical use," said V. Gerard Comizio, a partner at Paul, Hastings, Janofsky & Walker LLP. "Especially for a healthy institution, or relatively healthy institution, the idea of coming up with a contingency plan today for breaking the company up for a situation that may not arise for a number of years, does not seem to be practical. That kind of analysis is always going to be based on the structure and facts on the ground at the time. The best plans will be those that are closer to the time when they need to be implemented."

Harvard University professor Kenneth Rogoff said firms would "have to change" wills "all the time."

"Firms acquire new firms. They change their lines of business," he said.

"It will certainly create a lot of work for lawyers and help stimulate the economy. It's not a bad exercise to go through, but I think it better not be our only line of defense."

But many countered that while the wind-down plans would not be a cure-all, they could still provide important information about a firm's inner workings, putting the government in a better position to react to a crisis than last fall, when it showed an utter lack of preparation.

"The idea is a fairly common-sense one, which is to say that if you have these subsidiaries and affiliates that deal with each other — tell us how you would unwind them to minimize the kind of problems we had with Lehman's wind-up," said Douglas Elliott, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and a former investment banker at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

"I expect there will be objections" from large banks "based on the cost and effort" of completing the wills, Elliott said. But "it just seems to me we need to know the answers to these questions. If the companies already know the answers, it's not that much work. If they don't know the answers, we need to find out."

Officials say that while a resolution will not be identical to a firm's wind-down plan, the road map is still crucial to giving authorities a head start when a company begins to spiral.

"I don't think anyone views the … living wills as being a 'check-in-the-box' exercise in a crisis," said Michael Krimminger, a special adviser at the FDIC, which has been supportive of the resolution plan being in legislation. "You're basically getting to a place where the firm is structured in such a way that you've greatly diminished the complexities of doing a wind-down versus if you haven't done the living will."

He compared the pre-drawn resolution plans with a military strategy, which is not always identical to the actual battle.

"One famous general put it: The strategy is designed to put you in the position you need to be in so that when the battle starts and everything goes wild, you're in the best position to start from," Krimminger said.

Policymakers outside the U.S. agree the wind-down plans are a necessary component for global regulatory reform. Regulators in the U.K., for instance, are working on guidance for how systemically risky firms should develop living wills.

"By the end of 2009 a small number of major U.K. banking groups will have begun to produce living wills as part of a pilot exercise intended to help" the country's Financial Services Authority "develop policy in this area," the FSA said in a recent press release.

Petrou said U.S. regulators could similarly act now to make the wills a requirement, even without a bill from Congress.

"They have full authority to mandate them for regulated institutions, including banks and broker-dealers," she said. Also, "state insurance regulators could require them" for insurers.

Others said that even if a resolution plan differs from the actual wind-down, it is still important for companies — which may not have considered the prospect of their failure — to start thinking about it.

"They're worth doing, because I don't think the large banks have given enough thought to how these things would be unwound," Elliott said.

"However, I wouldn't exaggerate" the benefits of the plans, he added. "The benefits are relatively small but still worth it."