Second of three parts

It's fair to say that there is more than a little hostility to the concept of fair value, and the hostility intensifies depending on the instruments under discussion.

For some bankers, accounting standard-setters' ongoing search to define "fair value" for traditional loans is almost heretical. But there are fewer grounds for objecting to the application of fair value to securities, which, after all, are created primarily to make illiquid assets liquid.

Companies have used fair value for years. The Financial Accounting Standards Board's decision to adopt a new standard on fair value, issued in October of last year, was intended merely to clarify its use and identify methods for valuing increasingly complex securities that have poured into the market.

The seizure of markets once presumed to be liquid has complicated what was to be a no-hassle transition to the new standard, FAS 157.

"Companies and their auditors are really nervous about changing values, and they are nervous about whether they could be second-guessed" on securities valuations, said Dennis Beresford, a former FASB chairman and now a professor of accounting at the University of Georgia and the director who chairs Fannie Mae's audit committee. "It's awfully hard for some people to believe that markets could have changed so quickly."

The organizing principle of FAS 157 is a three-level liquidity hierarchy for financial instruments. Valuation is simple enough for Level 1 securities, which are traded actively in liquid markets with regular, quoted prices. For these securities, fair value is market value, and the math is straightforward.

Common equities and highly liquid U.S. Treasuries generally are considered Level 1 securities. For those securities quoted by bid and ask prices, companies can choose either the midpoint or the point between them that is "most representative" of fair value.

But the association between fair value and market value starts to break down with Level 2 securities, which are not quoted directly or traded actively but have "observable inputs" — market prices of similar securities, for instance — that can be thrown into models.

Common interest rate swaps, options, and other derivatives frequently fall in this bucket, as do licensing arrangements and even buildings. Agency mortgage-backeds, corporate debt, and some collateralized debt obligations fall into this category, as well.

Level 3 of the fair-value inferno is reserved for instruments that have "no observable inputs." The value of these instruments is almost entirely model-driven. They are worth what the company says, provided it can get its auditor to bless the calculated value.

This bucket, by and large, is the home of mortgage servicing rights, asset-backed commercial paper, and structured products like synthetic CDOs.

"The fair-value measurement objective remains the same, that is, an exit price from the perspective of a market participant that holds the asset or owes the liability," the standard reads. "Therefore, unobservable inputs shall reflect the reporting entity's own assumptions about the assumptions that market participants would use in pricing the asset or liability (including assumptions about risk)."

That's a lot of assumptions. Even granting the standard's comprehensible internal logic, figuring out which securities qualify as what is not always clear. Companies can reach different conclusions about the level and value of securities that seem similar. Value depends on the models, which can vary from company to company and produce wildly varying results, depending on the inputs.

"These values for Level 2 and particularly Level 3 are not as precise as the financial statements might imply," Prof. Beresford said. "But what they don't tell you, and probably couldn't very accurately, is tell you what kind of range we're talking about."

It is, of course, the Level 3 instruments that have gotten the most attention since markets dried up, given that their value is based largely on internal — if audited — assumptions. Investors have taken a dim view of these assets; the larger the portion of these assets, the larger the perceived black hole in the balance sheet.

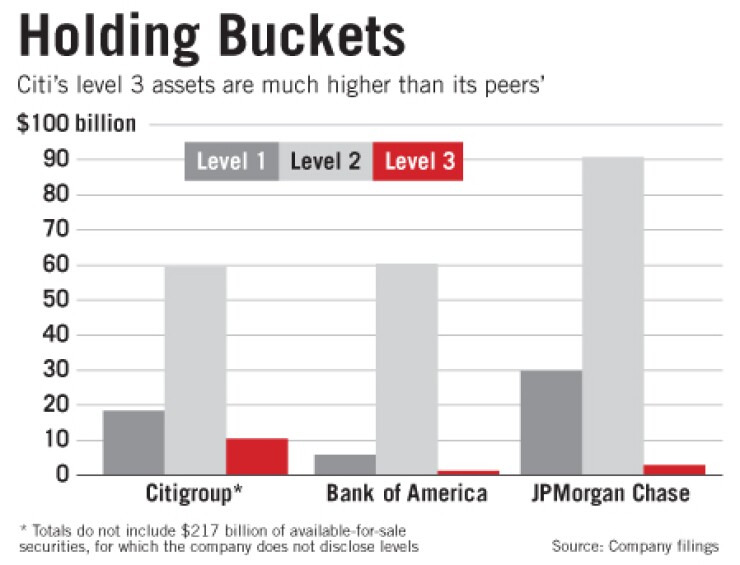

As of Sept. 30, Citigroup Inc. held $135 billion of Level 3 assets, JPMorgan Chase & Co. held $55 billion, and Bank of America Corp. held $28 billion. Spokesmen for the companies would not make executives available to discuss their use of fair-value accounting.

"Level 3 raises a reasonable question: If an asset is hard to value, should you be buying it at all?" asked Donald van Deventer, the CEO of Kamakura Corp., which helps companies and investors value securities. "The answer is probably no, unless you are really good at the analytics."

Banking companies could argue reasonably that they are good at the analytics, and that as financial intermediaries, they must be expected to hold a variety of instruments, including those not easy to value. But then the companies must live with the questions that arise from holding them.

"If an investor, in deciding whether to buy shares of a particular bank, sees a huge fraction of its assets are Level 3, the investor may wonder if the assets are worth as much as the bank says they are," said Darrell Duffie, a professor of finance at Stanford University's Graduate School of Business. "That's a discipline on the bank. It's helpful information for the investor making that decision, and banks will be forewarned not to load up on Level 3 assets if they want to sell at high multiples in the market."

Most accountants are quick to remind that the three-level hierarchy was a rough element in the accounting literature even before the FASB delineated it clearly in FAS 157. Fair value is a central element of FAS 115, a 1993 standard. Under that standard, securities held in the trading portfolio — the portfolio in which the largest U.S. banking companies keep most of their securities — are marked at fair value, with the aggregate change running through the income statement.

Banking companies that do not have substantial investment-banking businesses — from large regional ones to community ones — are more likely to keep their securities in the available-for-sale portfolio, which also is marked at fair value. Though the unrealized gains and losses in that portfolio are reflected in GAAP capital (regulatory capital calculations do not include unrealized gains or losses), they do not hit the income statement as long as they are relatively insignificant and reasonably likely to be recovered in future periods.

(Companies lose that safe harbor if losses are serious enough that recovery becomes unlikely. Zions Bancorp. reported one of the most recent instances of other-than-temporary impairment. In a securities filing Dec. 20, the Salt Lake City company, which has not adopted FAS 157, disclosed a $94 million impairment of CDOs in its available-for-sale portfolio and said it would record the entire amount as a charge to fourth-quarter earnings.)

But despite some accountants' frequent refrain that nothing has changed, the accounting, in fact, has changed — in the model itself, in its perception by investors, and in its disclosure.

"The auditors under 157 are establishing a high hurdle. They presume that if there are several transactions in a market, then these are willing sellers and willing buyers — and therefore, the value that you have to use," said Neri Bukspan, the chief accountant at Standard & Poor's Corp. "You had better have a good reason for deviating from market indicators, even if the market is characterized by very light trading."

Rebecca Shortridge, a professor of accountancy at Northern Illinois University, said that while that somewhat reduces the leeway that banks have in valuing their securities, the standard is "still extremely subjective about what assumptions you use to measure value."

There has been one big change: "Now, the assumptions are disclosed, where before they weren't — you can see if the assumptions are reasonable," Prof. Shortridge said. "You didn't have any way to judge them in the past."

Prof. Beresford said that in the past, "if a company had to account for something at fair value, they didn't have to say that it was determined based on models or references" to other prices. "They simply said it was at fair value, period."

Part Three: Why many remain skeptical about