Commercial real estate lending has officially made a comeback at SunTrust Banks. The Atlanta-based regional banking company posted a 20% annual increase last year in average performing loans backed by CRE, with about half the rise coming in the fourth quarter.

It has been a long time comingsix years since the onset of the recession and with it a sharp downturn in the industrial, hospitality, office, multifamily, and retail commercial property markets.

"Commercial real estate typically lags the start of the recession going down and it lags the recovery from the recession coming out," says Walter Mercer, SunTrust's head of CRE lending.

Over the last year clear signs of a recovery have been appearing around the country: property prices are up, overall mortgage debt is rising, and investors are injecting new equity into property deals. Just as importantly, the industry has continued to slough off loans that turned bad in the wake of the financial crisis.

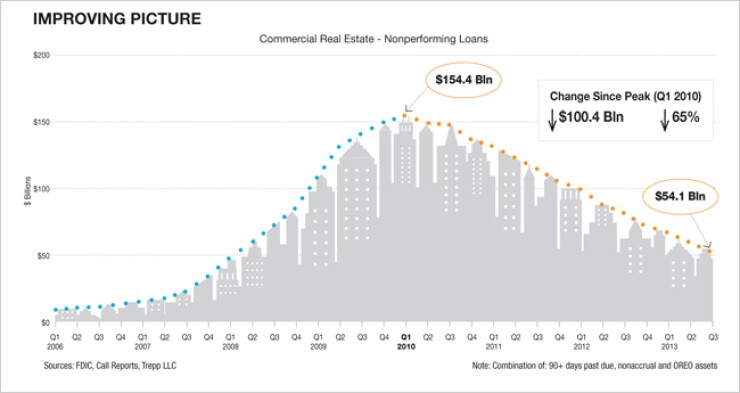

At their peak, in early 2010, nonperforming CRE loans put $154 billion of pressure on the balance sheets of U.S. banks, according to an analysis of Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data by Trepp, a New York-based firm that tracks the CRE market.

"There's a decent-sized drop there," says Matthew Anderson, managing director in Trepp's Oakland, Calif., office. "They have shed $100 billion of problem assets."

There's still work to do, however, especially for smaller banks and those competing in smaller markets.

National banks and large regionals have had an easier time finding investors to buy up their troubled real estate exposure, because the properties involved tend to be more attractive. This is partly due to the larger scale of the projects financed by bigger banks, and partly due to pricing that is at or above the 2007 peak for many major markets.

According to Moody's/RCA Commercial Property Price Indices, an all-property composite index, prices nationally in November 2013 remained about 10% off the peak in November 2007, representing a recovery of three-fourths of the peak-to-trough decline in values. But the averages are skewed by the major markets. Outside those markets, prices have recovered only slightly more than half their decline in values.

"The challenge now is there are a lot of small, lower quality assets out there," says Paul Brenneke, founder and CEO of Guardian, an Atlanta-based real estate investment banking firm that has found buyers for troubled loans and in some cases helped banks rebuild their capital base.

"You go outside the top 100 or 200 banks, then you start to get into the sub-$5 billion or $2.5 billion smaller banks. They still have bad assets they've been nursing along for years," he says.

The worst excesses occurred, of course, in construction and development loans. Gerard Cassidy, bank analyst at RBC Capital Markets, Portland, Maine, compares the debacle to the drubbing banks took on CRE in 1990, when losses followed a glut of new-construction office buildings. Only this time around, the worst excesses occurred in single-family developments and condominium projects.

MBank of Gresham, Ore., is one community bank that struggled against the odds after land values collapsed. The bank had $230 million in loans when the housing bubble burst, including $80 million in land development loans for single-home construction.

"We experienced extreme pain as subdivision after subdivision dropped off and developers walked away from loans and handed us deeds," says Jef Baker, MBank's president and CEO.

Almost overnight, a parcel of land once worth $1 million dollars, against which the bank might have lent $700,000, was suddenly worth just $100,000 to $200,000, he recalls.

Baker, at the time the bank's chief financial officer, concluded in 2010 that MBank had only a 5% chance of survival, and he urged his fellow executives and the board to move more aggressively to sell off the properties classified as other real estate owned. At first, the others were reluctant. "We just couldn't believe how much [of a] loss we were going to have to take and we held onto them much longer than we had to," says Baker.

After he was made president in October 2011, Baker called on Guardian to help locate buyers from around the country. The vigorous effort that followed to dispose of troubled assets allowed MBank to reduce its overall loan portfolio from $230 million to $125 million, even as it has made new CRE loans, Baker says. MBank was sometimes willing to extend loans to the new owners of properties, when there were new equity infusions, and in the process turned some nonperforming assets into performing ones.

Selling off bad assets helped the $173 million-asset MBank fortify its battered capital ratios, but more capital was needed. Last year, Guardian helped the bank raise $2.5 million in a private placement. The bank is operating under a regulatory consent order, but Baker hopes to be able to convince the FDIC to lift that soon.

Nationwide, bank-held construction loans have declined two-thirds from their peak of $631.8 billion in the first quarter of 2008 to $206.1 billion in the third quarter of 2013. And the percentage of construction loans categorized as noncurrent has dropped from a high of 16.8% in early 2010 to under 5%. (That's still elevated by historical standards. In the first quarter of 2006, for example, the noncurrent rate for construction loans was just over 0.4%.)

But despite the dramatic pullback in construction loan balances, CRE lending overall has been growing. Nonfarm, nonresidential lending secured by real estatethe largest FDIC subcategory for CREhas risen from $990.5 billion early in the first quarter of 2008 to just under $1.1 trillion in the third quarter of 2013. Multifamily loans held by banks also rose over the same period, from $208.3 billion to $252.3 billion.

"The real estate business is definitely looking up and banks are much more active than they were two years ago," SunTrust's Mercer says.

But the overhang of nonperforming assets remains a concern. The $54 billion in third-quarter exposures to nonperformers compares with a pre-crisis range of $10 billion to $15 billion.

According to Trepp, nonperforming CRE loansa combination of 90-plus days past due, nonaccrual and real-estate owned assetsrepresented 3.5% of CRE loan assets held by all FDIC-insured banks in last year's third quarter. That's down from a high of 8.8% in the first quarter of 2010, but well above the 0.6% ratio in the first quarter of 2006.

"There's 30% to 40% still left that are still lingering just a little bit under water," Guardian's Brenneke says. "Some have equity but not enough to refinance."

For banks, the peak year for maturities came in 2012, when $213.1 billion in commercial mortgages came due. Maturing mortgages dropped to $211 billion in 2013 and will fall further to about $186 billion this year. Trepp forecasts that the trend line will continue in this direction, with maturities falling to an estimated $31 billion by 2022, as loans made in the lean years after the crash reach maturity.

But for commercial mortgage-backed securities, the peak years for maturities lie ahead. The term for loans in CMBS pools is typically set at 10 years, versus three years to seven years on CRE bank loans. In the CMBS market, which has $62.2 billion coming due this year, maturities will rise to $137 billion in 2017 before falling sharply in 2018 to $42.8 billion, according to Trepp.

Brenneke estimates that a big slice of the $100 billion reduction in total exposure to bad CRE loans has come from cumulative markdowns that banks have taken against the value of the loans.

"It would be safe to say they have reduced their exposure because they've already written a lot of these down to a point where the numbers make sense," Brenneke says, noting that properties securing loans are now valued by banks at amounts that are much closer to real collateral values than they were three or four years ago.

Realistic markdowns also make it easier for banks to unload properties without shouldering additional losses.

Low interest rates have been another big help to banks trying to unload troubled real estate assets. Their impact has sped along the recovery in CRE, but also has underscored its fragility.

As Brenneke notes, interest rates on loans originated before the crisis typically ranged from 6% to 7%. With a new sponsor taking over a property and putting new equity into the deal, it is now possible to get a mortgage at about 4.5%, which significantly reduces carrying costs and potentially turns a property that was barely cash positive, cash neutral or even cash negative into a property with stronger cash flow. When that happens, the bank industry loses a troubled CRE loan and gains a performing onea phenomenon that could only occur in the current rate environment.

"If interest rates were higher," Brenneke says, "we'd still have a problem."

Robert Stowe England is a freelancer. He is based in Milton, Del.