Sometimes the biggest cybersecurity threat to a credit union is its own employees.

Desjardins Group, a Canadian cooperative, is learning this the hard way. It recently suffered a breach by an "ill-intentioned" employee in June that left data from 2.9 million members exposed.

The breach is the latest cautionary tale to the industry about the dangers of internal threats stemming from malicious employees who are willing to take customer data for criminal purposes. It’s an often overlooked aspect of cybersecurity.

"Technically speaking, one of the best ways credit unions can protect themselves is through limited access,” said Francis Dinha, CEO of security protocol firm OpenVPN. “Your private network should only allow certain resources to certain people — only the resources they need to do their jobs, and nothing more. With the right network tools you can limit access on a granular level, monitor data use across departments, and protect financial data by blocking it from any employee at any time.”

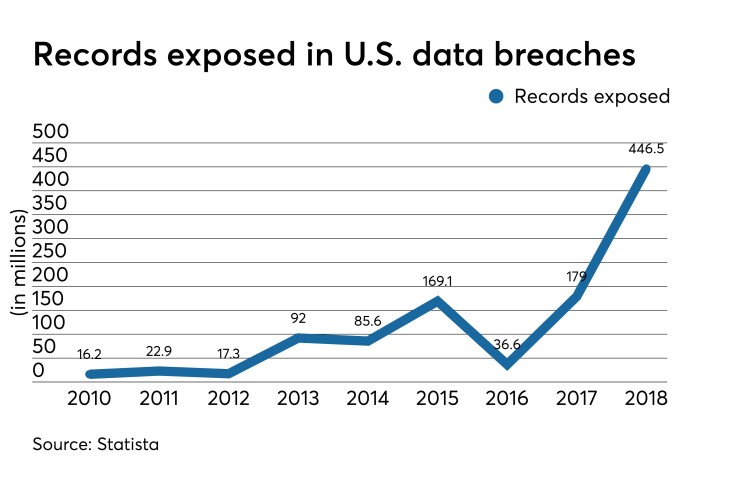

Cyberattacks stemming from internal threats are on the rise. The ENISA Threat Landscape Report found that 54% more organizations recorded a growth of insider threats during 2018. The 2019 Verizon Data Breach Investigation Report echoes those findings, showing that 34% of breaches happened due to insider actors.

One of the easiest methods for an internal breach comes down to the basics, said Milan Patel, chief client officer at the cybersecurity provider BlueVoyant. The basics start with an employee gaining unauthorized access to computers and databases that they’re not supposed to operate on.

Patel also noted that there are many cases where employees have walked right out the door of a company’s office with sensitive files in their backpack. Copying items to a USB drive are also fairly common and also one of the hardest methods to track, he added.

Internal bad actors are perhaps one of the more overlooked threats when it comes to an organization’s cybersecurity plan despite these attacks being made public by other institutions. Last year a

The breach at Desjardins, which is the largest federation of credit unions on the continent, is one of the most extensive in Canada’s history. An employee collected information on customers, such as names, date of births, email addresses and data on transaction habits, and shared that with a third party.

Security questions, PINs and passwords for both personal and business accounts were not compromised, according to a statement from Desjardins Group statement about the incident posted on its website. The organization's computer systems remained intact as well.

Desjardins did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The Canadian Credit Union Association also declined a request for comment.

“This situation is the outcome of unauthorized and illegal use of our internal data by an employee who has since been fired,” Desjardins said in the statement on its website. “In light of these events, and given the circumstances, additional security measures were put in place on all accounts.”

Following an internal breach, an institution should start with a full analysis to assess the extent of a breach and contextualize what someone may have taken.

In Desjardins’ case, Patel recommends a review all of its critical operational and customer data, and then a review of all employees who maintain access to its system. Implementation of a tool that detects improper use, such as additional usage of servers and data-hosting applications, is also recommended in unison with a user behavior analytics tool to oversee employee activity.

Desjardins now also has to navigate lawsuits, pay restitution and manage a reputational hit. The cooperative has a U.S. presence, including four branches in Florida. This makes adherence to data compliance particularly thorny since the cooperative needs to ensure it is following the laws of both the U.S. and Canada.

It could also open up Desjardins to legal and regulatory repercussions in both countries. Desjardins is facing class action lawsuits tied to the breach, though its potential legal exposure remains uncertain. The Florida Attorney General is also keeping a close eye on the situation.

"We are aware of the situation and will be actively engaging with the company to learn whether any Floridians were affected,” according to a statement from the state’s Attorney General’s office.

Desjardins’s breach touches upon the importance of credit unions being mindful of evolving data privacy laws. All 50 states have data breach notification laws, but at least 30 states have enacted or are considering bills that would amend existing laws, said Scott Wortman, a partner at Blank Rome.

But the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act requiring institutions to have "an affirmative and continuing obligation to protect a consumer's privacy and the confidentiality of their personal information," remains pretty concrete, Wortman said.

“[There’s] a question that regulators, whether it's federal regulators or regulators in the state, or I'm guessing regulators in Canada, too, are going to want to get to the bottom of,” Wortman said. “And that is: How did one employee have so much access to such highly confidential information?”