OKLAHOMA CITY — It's high noon for Frontier State Bank.

In a rare showdown between a bank and its regulator, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. took the $720 million-asset Frontier State to court this week. The agency wants the bank, owned by Joseph D. McKean Jr., to overhaul its business model.

The case is unusual for several reasons, not least of which is the fact that it has gone to trial. Bankers usually do not challenge regulators in public, though some observers said that as the industry downturn plays out, clashes like this could become more common.

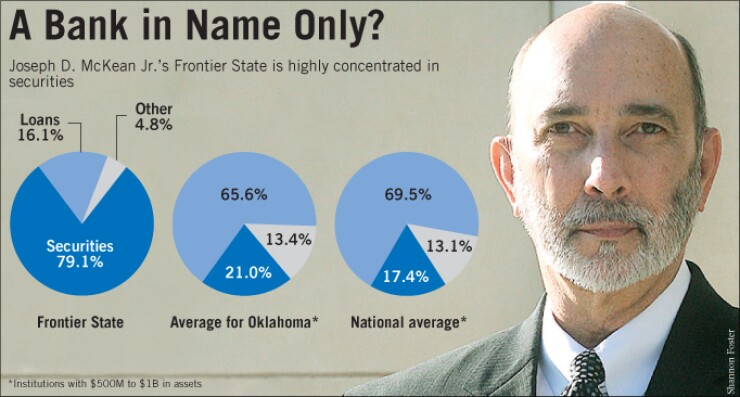

And Frontier is no ordinary bank. It has no offices other than its Oklahoma City headquarters. Its assets are highly concentrated in securities, and the bulk of its core deposits are from two customers: McKean and John Stuemky, a director. (Both men are physicians.)

Stranger still for a bank that has run afoul of regulators, its strategy has produced outsized growth and profits. Frontier State was considered well capitalized in April of last year, when the FDIC conducted an exam that led the agency to file a complaint against the bank in October.

In an administrative hearing, which began Monday in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, the FDIC claimed Frontier is unsafe and unsound, because it has been buying long-term securities with short-term funding, exposing it to rate swings.

McKean countered that Frontier is thriving, and that there is no need to change a formula that has worked for several years.

"Interestingly, the [FDIC] notice contains no allegations concerning either the bank's earnings or its asset quality," he said in an e-mail to American Banker. "Historically, banks have failed because of poor asset quality and depressed earnings."

Frontier "and its management have proven that the bank can make money using the so-called leverage strategy, and the bank has done so in a very volatile interest rate environment," he wrote.

One of Frontier's attorneys, Joshua Bock from Bracewell & Giuliani LLP, argued in court that nothing the bank is doing violates any law or regulation.

Since 2002 it has increased its assets almost 17 times over by buying collateralized mortgage obligations. On the funding side, it relies heavily on Federal Home Loan bank advances, federal funds, brokered deposits, large certificates of deposit — and McKean and Stuemky.

The hearing is expected to last through next week. After that, Administrative Law Judge Richard Miserendino will make a recommendation to the FDIC's board of directors.

The board will then issue a ruling, which Frontier, if it lost, could challenge in a federal appeals court.

Mike Hofmann, the president of Main Street Bank in Kingwood, Texas, said he noticed the hearing in a press release issued Friday by the FDIC, and he decided to travel the roughly 450 miles to Oklahoma City to watch.

"It is such a rare occurrence, I didn't want to miss the show," he said.

A spokesman for the FDIC said economic downturns typically result in an upturn in enforcement actions. That may result in more public hearings, he said.

There were 24 cease-and-desist orders issued in April, versus 20 in all of 2005, the spokesman said.

Industry watchers said there are many reasons why a bank usually would just comply with regulators' demands.

Chet Fenimore, the managing partner in the Austin office of Hunton & Williams LLP, often works with bankers on regulatory issues. He said it is difficult to win a case against regulators, because they are given broad discretion in supervising banks.

"What constitutes a 'safe and sound' banking practice is not a bright line," he said. "It is very different at the end of the day, and it is expensive to take it to this level. And, right or wrong, sometimes there is fear of retaliation" from regulators. "Bankers fear if they challenge a regulator, the next exam will come back and be worse."

Another reason disputes with regulators usually do not escalate to this level is because the banks involved are troubled and cannot afford the fight.

But Frontier State is making money. In the first quarter it earned $7.6 million, generating a return on equity of 44.88% and a return on assets of 4.18%. By comparison, Oklahoma banks with $500 million to $1 billion of assets returned 1.23% on assets, and the national average for banks of that size was 0.32%. The average return on equity in Oklahoma was 11.64%, and the national average was 3.36%.

Because most of the CMOs that Frontier State buys are backed by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac, the bank says, the credit risk is minimal. Of the bank's $721 million in assets, roughly 80% are CMOs. And close to 65% of the $556 million-asset CMO portfolio is guaranteed by the government-sponsored enterprises.

"It is somewhat unique in that this is still a very healthy bank, and the FDIC is challenging the strategy, and they are making a lot of money and not having any other issues," Fenimore said.

Frontier's attorneys say that is why it prefers to fight.

"Doing what the FDIC wants the bank to do would cost the bank a great deal of money in terms of lost income," said Sanford Brown, the managing partner of Bracewell & Giuliani's Dallas office.

Hal Oswalt, the president and chief executive officer of Brintech, a unit of United Community Banks Inc., said Frontier's model is not one he would pursue, though if he did, he would fight as long as he could to keep it. Waging a court battle is likely cheaper than changing strategy, he said.

"If that was the model I had pursued, I would fight that as long and as aggressively as I could to continue that revenue stream," he said. "If that was my strategy, and I am earning 4% on assets, I am going to continue that as long as I think that is a viable way to make that money. For each dollar they make, they probably feel they are ahead of the game."

According to testimony from the trial, Frontier's asset quality and earnings had ratings of 2 under the Camels system. (The ratings range from 1 to 5, with 1 being the best and 5 the worst. The ratings are seldom made public.)

But other areas were below that threshold. Frontier's capital, liquidity and sensitivity to market risk were rated 3, and the management rating was 4.

Frontier's capital was recently depleted when a nonagency CMO it owned was downgraded by a ratings agency. The bank's total risk-based capital ratio dropped from 18.71% at the end of December to 4.64% at the end of March, making it significantly undercapitalized, according to the FDIC.

But the bank's attorneys say those figures are misleading.

Brown said the capital shortfall resulted from "the risk weight that the FDIC has arbitrarily applied to performing private-label CMOs that are rated below investment grade by one — and only one — of the nationally recognized rating agencies."

The FDIC claimed that a test of Frontier's portfolio in the April 2008 exam found that the risks of the current asset and liability concentrations would be detrimental to the bank at its current capital levels.

One potential problem with the strategy of investing in long-term CMOs with short-term funds is that if rates increased, funding would reprice faster than assets, which would lose value in the market because the CMOs would be paying below-market rates and the payoff rate for the mortgages would slow. The bank could be stuck digging into capital, the FDIC said.

In its complaint, the agency said that a 200-basis-point jump in interest rates would cause the weighted average life of the portfolio to extend to 11.28 years, from 3.33 years, and that such a jump would cause the portfolio to drop in value by $82 million — or more than one and a half times Frontier State's Tier 1 capital.

The portfolio carries "excessive market, price and extension risk," the complaint said.

As of Dec. 31, 2007 — the data regulators worked with when they examined Frontier — the bank had core deposits of $309 million, with roughly 30% insured. The remainder of the $652 million of liabilities were borrowed funds.

Anat Bird, the CEO of SCB Forums in Granite Bay, Calif., said it does not appear as if Frontier is acting much like a bank.

"There is no core bank in it," she said. "It is a wholesale activity. You take the capital and maximize the earnings, but you don't invest money in the community. … The bank is taking advantage of an arbitrage situation. They aren't really doing banking. They are taking wholesale funds and investing them in securities. It is a risky strategy, because it has an interest rate mismatch, and liquidity is an issue.

"Banks who have done this in the past have failed faster than others," Bird said.

Michael Iannaccone, the president and managing partner of MDI Investments Inc. in Oak Park, Il., agreed that Frontier was not operating like a typical community bank.

"Regulators don't like people who run their bank like a hedge fund," Iannaccone said. "When they grant a charter to a group of people, and then the FDIC provides deposit insurance, there is a contract. Getting a charter and FDIC insurance means you will provide services to the community. The regulators now feel that the investor group is violating that contract by borrowing from the Federal Home Loan bank, brokered deposits and CDs. They are borrowing money that could be construed as the lowest crop available, and it isn't providing services to the community."

Oswalt said the large concentration is also a risk.

"It is pretty unusual from what I have seen for any community bank to put all their eggs in one basket like that," he said. "It'll work as long as the price of funding doesn't dramatically increase and they continue to have the right kind of funding mechanism. But what do they do … if it dramatically increases? The thing is, it may or may not work."

Jeffrey C. Gerrish, a partner at Gerrish McCreary Smith PC in Memphis, spent 35 years working for the FDIC, much of it as regional counsel, and he tried roughly half a dozen administrative hearings.

He said that more than once the administrative law judge took the side of the bank in his recommendation to the FDIC board.

Gerrish, who has organized a group called Community Bankers Revolt to challenge regulatory actions, said he expects more administrative hearings.

"In every region of the country they are under a tremendous amount of pressure, and they are doing things to cover themselves," he said. "You will find more banks are not going to roll over and consent, because either they can't take the inflammatory language or they can't do something they are being ordered to do."