Banks did not compete all that much for deposits last year, but the money flowed in anyway. If the first quarter of 2010 is any indication, however, this year may be different.

In the 7,200 banks for which the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. had posted first-quarter call report data as of Thursday, deposit growth had all but stopped, according to a review by Institutional Risk Analytics for American Banker.

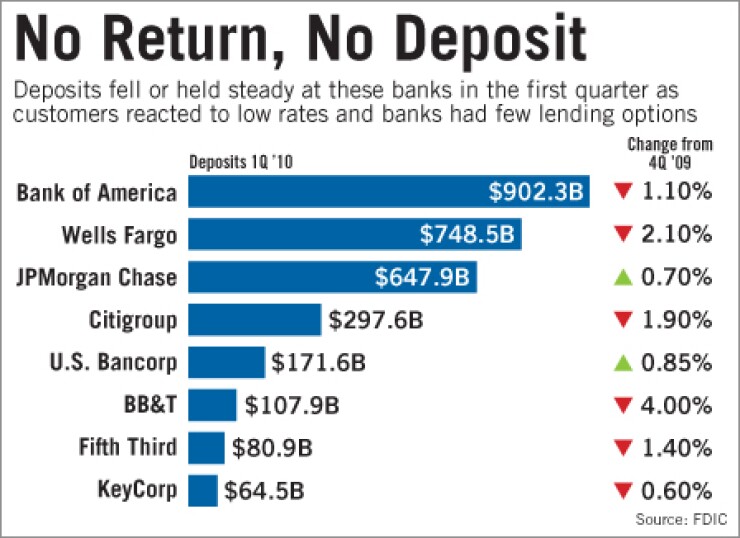

Among the four biggest banking companies, JPMorgan Chase & Co. was the only one to increase its domestic deposits, by 0.7%. Deposits at Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. all shrank by more than 1%. And though one quarter of data is not enough to establish a trend, some deposit pricing analysts see the first quarter as an indication that new money is about done flowing into the banking system.

"The first quarter of 2010, I see early indications this will be a tipping point, and it will most probably plateau, or there will be a slight decline in total deposits," said Dan Geller of Market Rates Insight. Assuming nothing comes along to spook retail depositors or corporations, he said, "the competition is not going to be among the banks themselves as it will be the banks versus other opportunities."

In a strengthening economy, individual depositors are more likely to shift funds into investments like stocks, and corporations draw down cash to spend on inventory.

The ramifications of such a shift would not be immediate, Geller notes, given that the banking system is still absorbing some of the $500 billion in deposits it added last year.

"There is quite a big sum of reserves sitting there," he said.

Dennis Santiago, the president of Institutional Risk Analytics, saw the slight drop in the biggest banks' deposits as a possible sign that smaller institutions may be competing better on the margins.

"If preference from the available market is shifting toward smaller banks on the individual depositor end, and trust institutions on the institutional end, that could mean these institutions would have to work harder," he said. "It may change the nature of the business that they're in."

At the moment, competition is light. Data from Market Rates Insight shows that the top five banks are offering lower certificate of deposit and money market rates in major markets like New York and California than their smaller rivals.

Data compiled by William Moreland of Dallas-based PeerMetrics show that last year timed domestic deposits dropped by nearly $400 billion, and brokered deposits fell by around $100 billion, declines of 14% and 16%, respectively.

Banks' funding costs were dropping, but not just because expensive certificates of deposit were maturing. They were dropping because fewer of their customers were in such products at all, experts said.

And with loan demand weak, many lenders have had less incentive to aggressively pursue deposits.

Not everyone believes that deposits are necessarily on the decline. Richard Davis, the president and CEO of U.S. Bancorp, cited his company's expanding deposit base during a talk at the UBS Financial Services conference this week. His company's quarter-over-quarter deposits were up by 85 basis points.

"I actually think, as rates go up, savers will be more emboldened to actually try to save more," Davis said.

"People are actually more excited to save when they can see something coming from those monthly returns."

Any rise in the cost of deposits would be a step toward reversing the significant declines in funding costs that most banking companies — but especially the biggest ones — enjoyed last year. According to data compiled by Moreland, the average cost of bank funding fell to 111 basis points at the end of 2009, down from 185 points the year before. Among banking companies with more than $1 trillion of assets, the average cost of funding at the end of 2009 fell to just 80 basis points.

The diversity of cheap funding opportunities for the largest banks may partly explain why their deposits did not rise last quarter, said Terry Moore, the head of Accenture's retail banking practice. Midsize regional banks, particularly those still struggling to repay federal bailout funds, need deposits far more and are willing to pay up for them.

"That's not a sustainable approach," he said. "Some that aren't going to be able to generate those deposits won't be able to effectively compete from a profitable growth perspective."