WASHINGTON — While it's clear that tighter rules for securitization are on their way, varying approaches to the issue by different agencies are making bankers and issuers uneasy.

At worst, government efforts to rein in issuers of asset-backed securities could produce three separate regulations, each with its own elements. While the three rules would all largely do the same thing — strengthening disclosure and requiring issuers to retain 5% of the credit risk from a securitization — they have significant differences.

Industry representatives said they hope the three proposals — one from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., one from the Securities and Exchange Commission and a joint rule by several regulators required under the Dodd-Frank Act — can be harmonized, but they said the variance between them is making it difficult to prepare for the reforms.

"When there are all these balls up in the air, you can't expect businesses to make systems changes … until the dust settles," said Cristeena Naser, a senior counsel for the American Bankers Association. "They need to be coordinated. Nobody is saying that we don't need changes to the process, but we need a uniform change to allow businesses to make decisions."

Regulators said that, though there is coordination across agencies, the FDIC and SEC are pursuing separate paths because they each deal with specialized jurisdictions. The FDIC's May proposal is specific to its failed-bank duties, while the SEC's rule addresses its unique role deciding which players can get expedited registration to issue ABS.

"Every regulator has jurisdiction over certain areas, and we have jurisdiction over the receivership rules. The SEC has jurisdiction over the securities rules," said Michael Krimminger, the deputy to the FDIC chairman for policy. "Just because someone comes out first with a rule and someone comes out second with a rule that deals with similar issues doesn't mean they haven't been harmonized or coordinated. They have been."

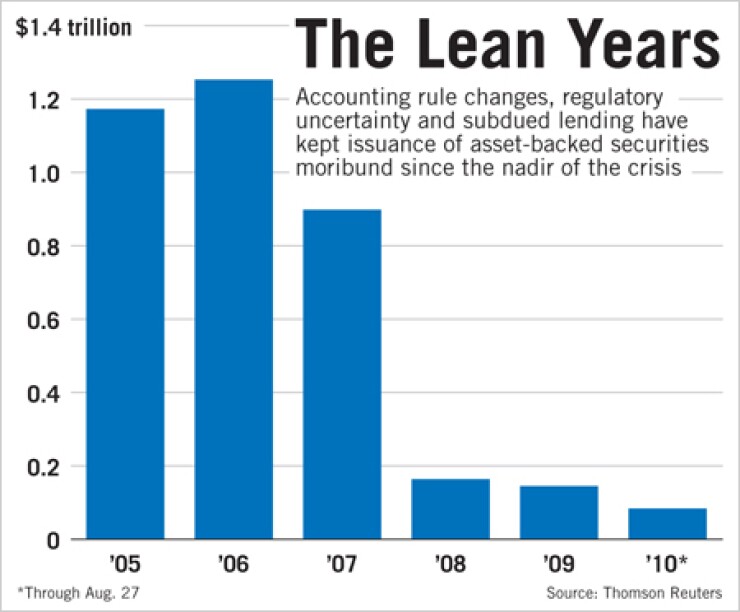

Securitization has been in regulators' cross hairs for more than a year. Last summer, accounting rules required banks to put previously unreported securitizations on balance sheet.

The accounting change effectively invalidated a long-standing FDIC policy — referred to as a "safe harbor" — of not claiming such unreported assets in a failure. But industry representatives said that without the safe harbor, investors would be scared off from securitizations.

As a result, the FDIC issued an advance notice of proposed rulemaking that said it would continue to grant the safe harbor to securitizations, but proposed several conditions for receiving the special status, including tranche and compensation limits, stronger disclosure modeled after the SEC's Regulation AB and a 5% retention requirement.

Meanwhile, the SEC proposed strengthening Reg AB in April, with a 5% requirement for public issuers if they desire "shelf" registration, a process that speeds up the ability to issue securities, as well as tighter disclosure for both public issuers and certain private issuers.

But as the two agencies develop the regulations, they also face the task of implementing — jointly with four other regulators — similar provisions enacted by Dodd-Frank. The law, which was signed July 21, requires all six agencies to write rules that would require lenders to retain some risk on the loans they sell.

Krimminger said there are no gaps between the FDIC and SEC on risk retention and disclosure, and the new law similarly uses the 5% standard, meaning issuers should have a clear sense of what the standards will be when the rulemaking process is finished.

"There would be no daylight between the SEC Reg AB proposal, between our NPR proposal, and between Dodd-Frank right now for risk retention, since 5% is the baseline standard in Dodd-Frank," he said. "If I were in the marketplace, I'd say, 'Looks to me like it's 5%.' "

But Naser noted discrepancies between the different regimes.

For example, while the SEC proposal exempts private issuers in certain areas, the FDIC plan would apply to all insured financial institutions issuing ABS, which includes private issuers.

Moreover, the new law, unlike the two regulatory proposals, provides for easing the retention requirement for certain safe residential mortgages and other asset classes determined by the regulators. Dodd-Frank also leaves open the possibility that an originator could share the 5% credit risk with the sponsor securitizing a loan, while the other proposals essentially say the sponsor would retain the risk.

"Much of the uncertainty in the securitization market derives from the different schemes for risk retention and disclosure, among other things, being raised by the Act, the Commission, and the FDIC," Naser wrote in an Aug. 3 comment letter to the SEC. "We cannot emphasize enough that for the securitization market to serve its function as a robust, economically feasible source of funding, it is critical that a single set of standards be placed for all of its participants."

Some observers said differences between the approaches are understandable, considering that the regulators are playing to different audiences.

"They … have to keep in mind their constituencies, and where their jurisdiction goes out to," said Howard Kaplan, a managing partner at Deloitte & Touche LLP.

Other observers said proposed standards from three different sources make it hard to anticipate which rules participants will have to follow.

"There's confusion in the marketplace not only about the number of trains running, but how fast each train is running," said Steven L. Schwarcz, a law and business professor at Duke University and an expert on securitization. "You don't know how to structure a deal."

Kenneth Morrison, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis LLP, said that since the different agencies regulate different constituencies, regulators should be wary about potential competitive inequities.

"There's a risk of conflict between the rules and there's particularly a risk for banks that they're going to be subject to more stringent rules under the FDIC safe harbor than nonbank issuers will have to follow under the joint agency rules and the SEC's revised regulation AB," Morrison said.

It is unclear if any of the regulatory efforts on securitization will be consolidated, but several observers said they should be. They argued that the work done already by the FDIC and SEC could be used to begin a joint rulemaking effort.

"There should be every expectation that the agencies will issue just one rule," said Jerry Marlatt, who is of counsel at the firm of Morrison & Foerster. The FDIC and SEC proposals "give a pretty good idea of what the agencies think the risk-retention policy should be," he added. "Now they need to reach a common ground. It's not like they're both starting from a blank slate."

John Heine, an SEC spokesman, suggested the pending proposals will contribute to the implementation of the new law.

"The comments we've received on the proposals will help inform the agencies as they work on Dodd-Frank rule proposals," Heine said. (The agency declined to comment further.)

But Krimminger indicated that the agencies' respective jurisdictional duties mean that ultimately they will have to issue at least certain provisions separately.

"There will be a rule on the safe harbor, because no other regulator has jurisdiction over our receivership rules," he said. "There will be a rule on Reg AB for shelf registration and private placements by the SEC, because no other regulator has jurisdiction over that. And then there will be a joint rule dealing with risk retention under Dodd-Frank, which deals with only part of the issues dealt with under the SEC and the FDIC rules."