In the end, was it all just blind ambition?

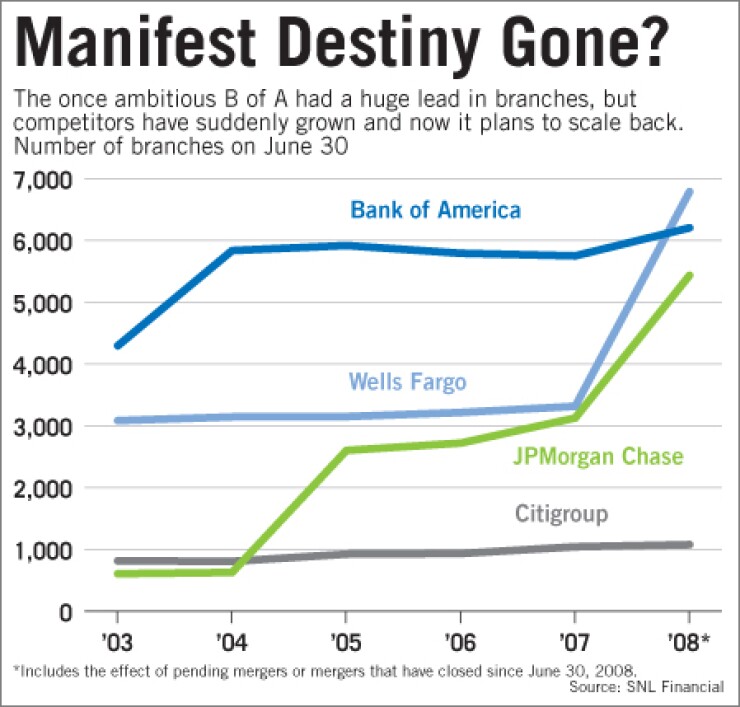

Famous for its desire to be the bank of America, Bank of America Corp. announced this week that it will shrink its sprawling branch system. For the Charlotte company, the move is a sea change in self-perception, from grand to … realistic.

Observers point out that CEO Kenneth D. Lewis has for years touted the need for scale and steadfast support for the U.S. consumer. But the prolonged recession and a belief that retail banking mores are changing may be reshaping the executive's philosophies, leading the company to cut back significantly on a branch network it spent years building, they said.

"I think they have moved away from the goal of doing business with every household in the U.S.," said D. Anthony Plath, a finance professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. "From now on, the emphasis is quality over quantity."

But others aren't sure whether to give B of A that much credit given the lack of details — the company has not said how many branches it will cut — and its constant changes of direction in recent years under Lewis. Far from a move of conviction and intent, the branch cutbacks could merely be another meandering strategic detour, they say.

"They have an identity crisis over who they want to be," said Gaurav Patankar, a managing partner at 360 Global Partners Inc., pointing to substantial executive turnover in recent years and the extra oversight that has come from securing $45 billion in capital from the government. "This goes beyond their scope and size."

In any event, observers said, thinking smaller, more high-tech — and more profitable — makes sense for a struggling company that is still trying to resolve huge credit-quality problems, digest some controversial acquisitions and fight off criticism from investors and federal officials.

Red Gillen, an analyst at Celent, a research and consulting unit of Marsh & McLennan Cos., said he expects Bank of America "to place considerably more emphasis" on improving its mobile and online technology. "New services are now probably a lot closer to the center of B of A's radar screen," he said.

But there are numerous examples of the $2.32 trillion-asset company charting a strategic course only to abandon it soon thereafter.

In the last five years there have been four chief financial officers, four general counsels and two chief risk officers. In the past year the company moved two key executives, Brian Moynihan and Neil Cotty, to new posts only to return them to their previous jobs a few months later.

Analysts recall a February 2007 conference in Florida where Lewis told attendees that he wanted growth without relying on acquisitions, only to spend nearly $46 billion over the next two years on U.S. Trust Co., LaSalle Bank, Countrywide Financial Corp. and Merrill Lynch & Co.

Bank of America also went from investing more than $500 million to build up its investment bank to an aggressive purge after a substandard quarter in 2007, when Lewis infamously declared that, "I've had all the fun I can stand" in the business. A year later he swooped in to buy Merrill, simply telling investors that, "I like it again."

Lewis said in an American Banker interview last fall that the 2007 comment was "reactionary" and had taught him a lesson. "Cute comments always get you in trouble, and they always come back to haunt you," he said.

Some are saying the same of the company's actions. Its bold bets on the U.S. consumer have given it substantial exposure to the recession.

Losses embedded within its trading book, notably those at the once-coveted Merrill, led to more government aid and oversight and contributed to Lewis' ouster as chairman in April.

The board has also been reconstituted, with Walter Massey promoted to replace Lewis as chairman, along with seven departures and four additions this year.

The frenetic pace of change, along with capital constraints, has heightened concern among observers who normally tout execution as B of A's greatest attribute.

Andrew Marquardt, an analyst at Fox-Pitt Kelton Cochran Caronia Waller, said B of A's "lack of consistency frustrates" investors. "Clearly it has been questionable if they have really stuck to their strategic initiatives," he said.

B of A spokesman Bob Stickler acknowledged the concerns but said the volatile economic conditions have to be taken into account.

"What they're seeing is that the road isn't always straight," he said. "We can understand people's frustration. Nobody likes to run in place, but it is better than falling down."

"We think Bank of America's strategy has been consistent, focusing on how do we grow the company. … We have been opportunistic. When things come up that fill holes in your franchise, you take advantage of that."

Not everyone is criticizing the company's willingness to change direction, particularly by scaling back its 6,100 branches — and their costs — to focus on alternative channels.

While Lewis told a group of investors last week that a 10% cut was possible, a B of A spokeswoman said Wednesday the company continually evaluates the size of its network, but it does not yet have a target.

Kenneth Thomas, a bank branching consultant, said banks can spend $1 million each year to run a branch, with half the costs tied to staffing.

Using that estimate, B of A could cut annual expenses by $610 million by closing 10% of its branches.

(It would have the third-biggest network, behind Wells Fargo & Co. and JPMorgan Chase & Co.)

"It would allow them to reallocate financial resources," said Darryl Demos, the general manager of the banking group at Verint Systems Inc., a Melville, N.Y., technology provider.

"Branches are only one small part of the consumer relationship. This is an absolute rebalance that would be natural for the company."