-

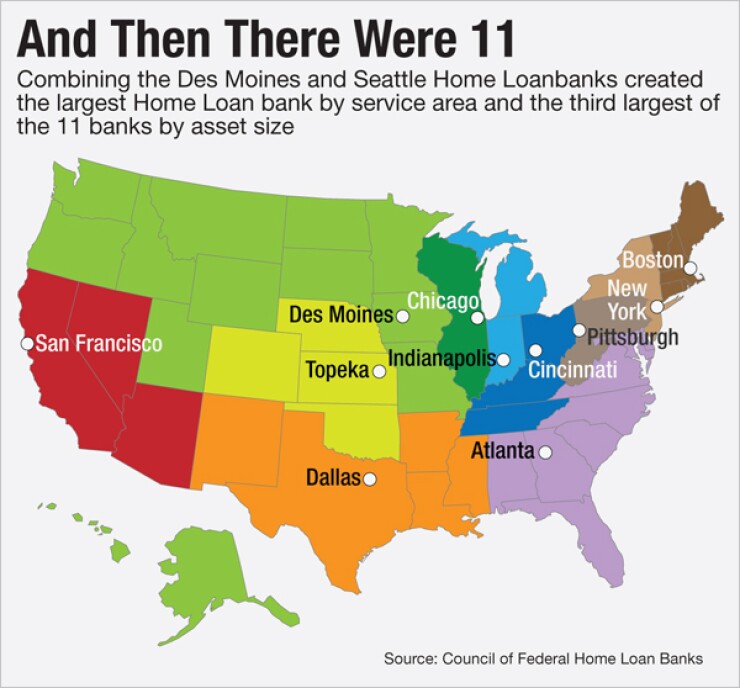

The merger of the Federal Home Loan Banks in Des Moines and Seattle became official on Monday, shrinking the overall number of banks in the system to 11.

June 1 -

WASHINGTON The Federal Housing Finance Agency said Monday it has approved the merger of the Federal Home Loan banks of Des Moines and Seattle, giving approval to the first voluntary combination in the history of the system.

December 22 -

The proposed merger of the Home Loan banks in Seattle and Des Moines could spur massive consolidation among their sister banks, but only if the two show it's possible to overcome governance and other logistical challenges that have deterred similar deals.

August 4

WASHINGTON Nearly a year after they first announced their intention to combine, the Home Loan Banks of Des Moines and Seattle completed last week the first voluntary merger in the system's history.

The details of the final deal made it clear why this merger worked when past attempts had not and gave clues as to whether other institutions could one day follow suit. Following are three items that jumped out:

This was not a merger of equals

The Des Moines-Seattle merger was billed as one of equals and not an acquisition. But it's clear that's not the case. The Des Moines Home Loan Bank has three times the assets and earnings and six times the advances of the Seattle bank. The headquarters of the combined bank stayed in Des Moines and the chief executive of that institution leads the newly merged bank.

Seattle was in need of a merger partner given its dwindling advances, with only $10.3 billion at yearend 2014. Advances are the traditional business of Home Loan Banks and their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, has been strongly encouraging them to focus on that area. Of the 12 Home Loan banks, Seattle had the lowest amount of advances. Only the Dallas and Topeka banks have advances of less than $20 billion.

Seattle's dearth of advances was primarily due to the failure of Washington Mutual in 2008. The Seattle bank had $36.9 billion in advances at that time, but since then it was struggling.

The Des Moines bank, meanwhile, has enjoyed a resurgence over the past few years. Advances have jumped to $65.2 billion in 2014 from $26.6 billion in 2012. To be sure, however, the bank relies on borrowings from its largest member. Wells Fargo Bank, with a charter in Sioux Falls, S.D., is responsible for $34 billion by itself.

"The increase in advance volumes was due to borrowings from a wide range of members with the most significant increase from a large depository institution member," spokeswoman Angie Richards said in a written response to questions from American Banker.

Due to the merger, Des Moines moves up one rank to become the third largest Home Loan Bank of the remaining 11 banks in terms of assets and advances.

The merged bank jettisoned half of its mortgage holdings

As part of the merger, the Seattle bank sold its entire portfolio of private-label mortgage-backed securities and netted a very small gain. Like many Home Loan banks, Seattle stocked up on such securities when the subprime, alt-A and hybrid adjustable-rate mortgages were popular.

By the time the mortgage market blew up, the Seattle bank had $542 million in unpaid principal balance in private-label securities on its books. After taking an impairment charge of $304 million in 2008, Seattle's portfolio had an amortized value of $242 million.

"In connection with the merger, during March 2015, we formalized the decision to dispose of the PLMBS," the Seattle bank said in a recent securities filing. "As a result, we determined that we no longer had both the ability and the intent to hold all our securities classified as HTM (held to maturity) to maturity."

The Seattle Home Loan Bank realized a gain of $52.3 million on the securities sale. But that gain was offset by a $51.5 million charge in accounting losses. As a result, Seattle's net gain on the sale was just $792,000.

The sale cleans up Seattle's balance sheets to reflect its partner.

"Des Moines is carrying just $24 million (amortized cost) in PLMBS on our books in the held-to-maturity investment portfolio at the end of March 2015,"the spokeswoman for the merged bank said.

The other 10 Home Loan banks have over $21 billion in private-label securities remaining on their books. It's unclear if other banks may also decide to unload those securities, but it is unlikely in the current low interest rate environment.

The merger was successful partly due to close ties between top officials

The Home Loan Bank system has seen one failed merger negotiation in the past decade, after the Chicago and Dallas banks unsuccessfully tried to combine several years go. The Seattle-Des Moines merger worked due to a number of factors, including adjacent districts and economies of scale, but was also significantly assisted by close relationships between senior officials. That could mean the merger is more of a one-off event.

Michael Wilson, the Seattle bank's president and chief executive, was formerly the chief operating officer at the Des Moines bank, serving under its president and CEO, Richard Swanson, from 2006 through 2011. Some of Des Moines' board of directors had also worked with Wilson.

In the merged bank, Swanson and Wilson will split the top two posts. Swanson will continue to serve as CEO until June 30, 2017, when he is expected to retire. He earns a base salary of $720,000, according to public filings. Wilson will serve as the merged bank's president and also receives a salary of $720,000. He is likely to take the CEO role when Swanson retires in two years.

The merged bank has expanded its board of directors to accommodate all the 14 directors of the Seattle bank and 15 from the Des Moines bank.

"We are pleased to have finalized this merger with overwhelming support from our members," said Swanson in a press release last week. "We believe that the continuing bank will be stronger by virtue of its larger and more geographically diverse membership base and can achieve operational efficiencies that will help maintain our sound financial condition over the long run."