WASHINGTON — The White House in the last few weeks has deployed everyone from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to First Lady Jill Biden to sell a very specific narrative — that the economy is doing well, and that President Joe Biden is responsible for it.

Voters are skeptical — and that might be a problem for banks.

Biden has long had an issue with the perception of his handling of the economy. Just 34% of voters approved Biden's handling of the economy in June, according to an Associated Press/NORC Center for Public Affairs Research

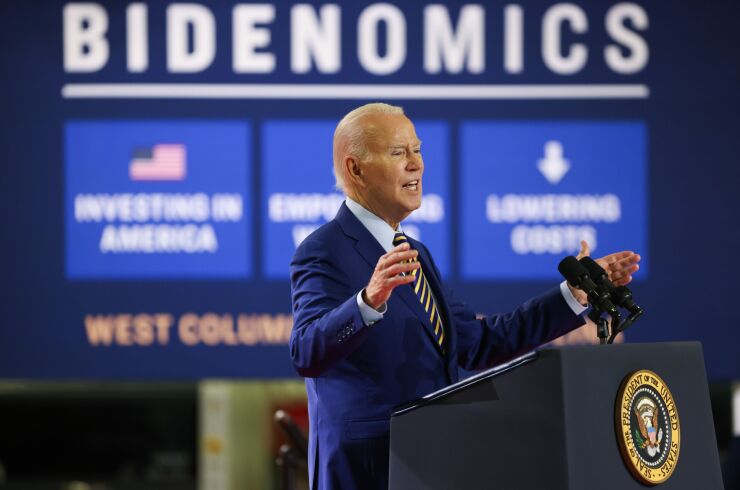

In recent speeches, Biden has heralded the infrastructure investments and job creation that's occurred over the course of his administration.

"I came to office determined — some on my own team thought I was too determined — to change the economic direction of this country, to move trickle-down economics and get rid of it for everyone," Biden said in a speech last week in South Carolina. "The Wall Street Journal to the Financial Times called the program 'Bidenomics.' I'm not sure they meant it as a compliment at the time.

"It's rooted in what always worked best for this country: investing in America," he continued. "Because when you invest in our people, when you strengthen the middle class, we see stronger economic growth that benefits everybody."

But experts point out that those gains are less tangible than persistently low wages, especially among lower or middle-earners despite some modest gains, or high inflation.

That leads to a sizable disconnect between how many likely voters feel about the economy, and how the Biden administration is presenting it, said Karen Petrou, managing partner at Federal Financial Analytics. That's true not just for Republicans, but for some Democratic voters as well.

"I think it is a very dangerous political tactic to try to persuade voters that something they're experiencing isn't happening," she said. "The rhetoric has to change, and he has to recognize the reality of many American households, particularly most likely voters, many of whom are doing worst of all compared to 2016 to 2019."

Wall Street's viewpoint is a little more complicated. On one hand, the stronger-than-expected labor market and other positive signs are prompting some of the country's largest financial institutions to signal strong times ahead for the economy.

"Even if the unemployment rate went up a few tenths of a percent from here, the labor market would still be in very good shape relative to history," said Wells Fargo's Scott Wren in a research note. "U.S. consumers with money in their pockets tend to go out and spend it."

And "Bidenomics" is a tricky term to pin down, especially for the financial industry.

"Bidenomics is merely whatever passes for economic policy these days," said Bert Ely, principal of Ely & Co. Inc.. "All very ad hoc."

But more specifically for consumer-focused banks, the White House's push to change the conversation around what the administration is doing for average voters could cause Democratic policymakers in Washington to focus more keenly on issues like so-called "junk fees" or on preventing bank mergers as part of a larger antitrust push.

"He's attempting to have a variety of pocketbook issues that he's going to run on and to have a counter to claims that his administration contributed to inflation," said Ed Mills, managing director and Washington policy analyst at Raymond James. "He's going to try to have another narrative as to where he's seeking to save the average voter money."

While those issues aren't necessarily at the forefront of most voters' minds when they think about the economy, they're still an important part of the Biden camp's messaging when it comes to how they will answer criticisms around inflation and other economic issues, Mills said.

In the run up to the 2024 presidential election, Mills said that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's bid to cap late fees at $8 will be a specific policy that Biden can point to, along with enforcement actions from the bureau. The CFPB on Tuesday

Petrou said that a change in messaging might also mean the Biden administration taking a more critical tone toward the Federal Reserve in the next year. As far as where macropolitics and financial policy collide, Petrou said to watch populist alliances like those between Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Sen. J.D. Vance, R-Ohio, in opposing large bank mergers.

Banks have already criticized the Biden administration for being too strict toward merger activity.

"You'll see a fair amount of that with the White House trying to hit that theme," Petrou said. "Where the banking agencies come down on that will be very interesting. Because they're being pushed between political and market reality, what are they going to do with the regional banks?"