-

Fifth Third has split the chairman and CEO roles after adding William Isaac to its board. The former FDIC chairman succeeded Kevin Kabat, who remains president and CEO.

May 28

Two years after embarking on a series of wrenching financial decisions, Fifth Third turns out to have been rather prescient about how bad the crisis would get.

The $113 billion-asset company is now widely viewed as being further along in the credit cycle than many of its peers as a result of its willingness to take quick, drastic action starting in June 2008.

Granted, Fifth Third still has yet to repay $3.4 billion of capital from the Troubled Asset Relief Program. But Fitch Inc. last week upgraded its rating outlook for the Cincinnati company from negative to stable, citing solid liquidity and capital ratios and a welcome moderation in credit trends. Nearly two dozen Wall Street analysts now recommend buying or holding Fifth Third's stock, versus four who say sell.

The hiring last month of William Isaac, an outspoken former regulator, as chairman suggests the company feels it is far enough along mopping up its messes to break with the industry's defensive posture and confront the broad regulatory changes coming down the pike for banks.

"The bank's view is that they got on top of the problems faster than most," Isaac, a former Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. chairman, said in an interview last week. "They paid a price for it in the short run because they were perceived as suffering more than others. But they also feel like they are going to be rewarded for it because they're going to come out of this faster."

That was exactly the way Chief Executive Kevin Kabat had been hoping things would play out for Fifth Third, which in addition to having all the problems one would expect of a regional bank in the midst of a financial crisis also had the unfortunate distinction of being heavily exposed to the housing bust's toll on Florida and the recession's impact on Michigan.

Three months before the failures of Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual Inc., Fifth Third began preparing for the worst, announcing a dividend cut, a $1.1 billion preferred stock sale and a plan to raise additional capital through a major asset sale.

Next came steep writedowns, and another, more dramatic dividend cut that would make Fifth Third the first of the major regional banks to slash its quarterly payout to a penny a share.

Big writedowns? Penny dividends? It sounds par for the course now. But at the time, such actions were considered alarming — not just because they signaled big trouble, but because for a company with concentrations in at least two major trouble spots, it was unclear whether all that would be enough. Raw land loans, which the company believed were especially risky, were marked down to roughly 30 cents on the dollar.

"We literally had people on the road, looking at each of these [troubled loan] properties and trying to get as broad a perspective and as much information as we could" to decide on the appropriate writedowns, Kabat said in an interview last week.

Asset sales conducted since then have been done at prices slightly above the written-down values.

"Even though we thought we were being overly pessimistic as to the outcomes, it turns out we were about right," Kabat said. "But that was a very difficult process with a lot of debate, a lot of consternation."

Kabat described the results of the government stress tests in May as a turning point for the company, when the market began to see the upside to measures that previously had been seen as red flags.

"It's always hard to tell whether companies are being conservative or aggressive at the time," said Jennifer Thompson, an analyst at Portales Partners LLC who has a "buy" rating on Fifth Third. "But they addressed the problems early. They built reserves aggressively and where they had the opportunity, they were able to sell assets faster than some of their peers because they had marked their distressed loans as well as they did."

Other changes involved less risk. Kabat estimates that internal pieces of communication (e-mails, memos, and so on) have increased 60% since the crisis began. He now addresses the 20,000 employees in periodic videos, and the company set up an internal blog, to which executives contribute.

Fifth Third also centralized its credit-decision and underwriting process — a big switch for a company that long prided itself on a decentralized "affiliate" model designed to keep authority in the hands of local market executives. As a former affiliate chief, Kabat said he was sensitive to the change. But he contends that service now gets delivered to clients quicker and more smoothly than before.

Kabat, 53, started his banking career at Merchants National Bank in Indianapolis and soon after joined Old Kent Bank, rising to vice chairman and president. Old Kent was acquired in 2001 by Fifth Third, which put Kabat in charge of a Michigan affiliate before bringing him to Cincinnati to oversee retail and affiliate banking. He was appointed president in June 2006 and CEO in April 2007, adding the chairman's title in June 2008.

He ceded the chairman's post last month to Isaac, now head of the financial services practice at the consulting firm LECG Corp.

Both Isaac and Kabat explained the move as a nod to corporate governance principles and to Isaac's ties with his native Ohio, his considerable regulatory experience and his familiarity with Fifth Third, an LECG client, thrown in for good measure. It was not, they said, a sign of dissatisfaction on the part of the board with Kabat's performance or the company's direction.

"We have made a ton of changes to this company. From a personal standpoint, I think the one thing that hopefully the market takes away from it is that I'm going to do everything in my power to make us best in class," Kabat said. "This [decision] was something I could participate in and demonstrate not only to the external world but to the internal world that this is how strongly I feel" about putting Fifth Third in good standing on governance issues.

As nonexecutive chairman, Isaac's main duty is to lead board meetings. But his presence also presumably gives Fifth Third a vocal advocate in a noisy political environment and could potentially make it easier for Kabat to stay focused on internal matters. (Both men said they are determined to keep the chairman post from interfering with Isaac's ability to freely criticize regulators, politicians, accounting standard setters and other frequent targets of his. "We don't expect to in essence muffle Bill from his personal opinion. I don't know if you could do that anyway," Kabat quipped.)

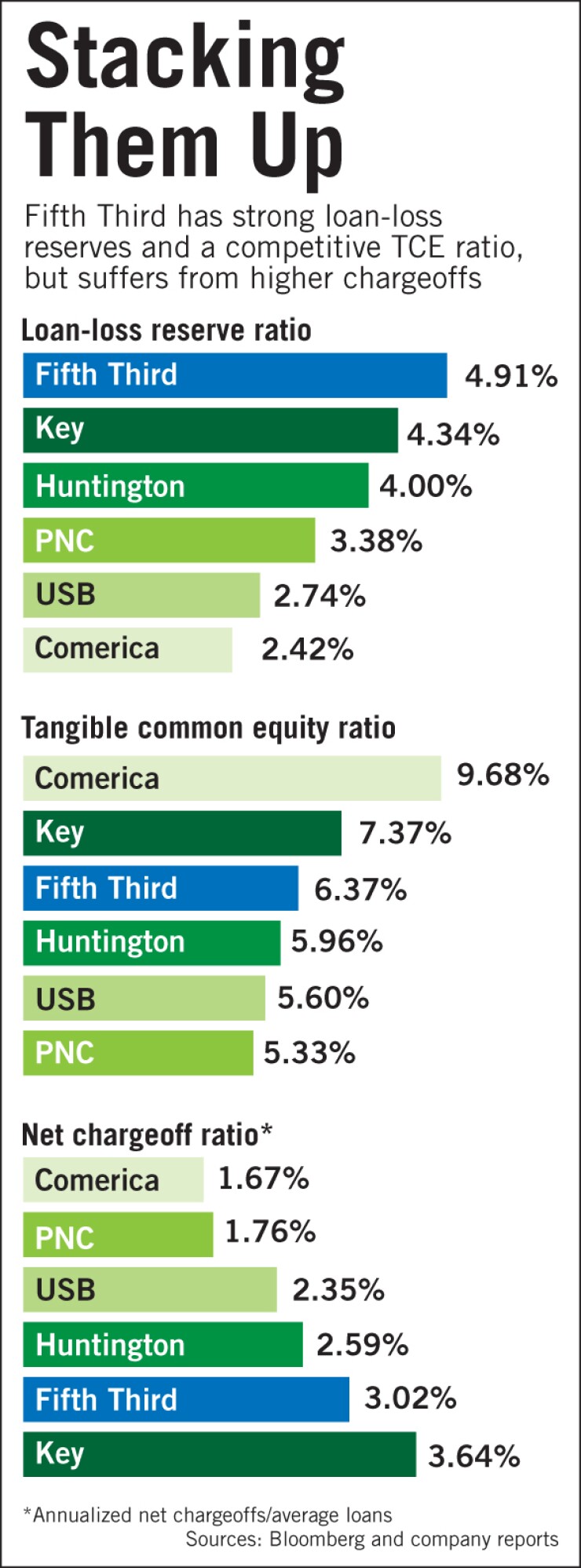

Instead, Kabat plans to focus on taming net chargeoffs, which remain high relative to other regional banks, and on developing a strategy for resuming growth.

On that front the company may have an advantage over rivals such as KeyCorp, which quit business lines such as boat and recreational-vehicle lending.

"None of our businesses have been fundamentally destroyed or shut or lost," Kabat said, although the company did give up 51% ownership of its processing unit last year to raise capital.

Between that sale, $1 billion of common stock issuance and other capital-stockpiling measures, Fifth Third raised about $800 million more than the $2.6 billion of additional common equity that last year's government stress test indicated the company needed. Fitch said in a June 9 report that it expects Fifth Third to repay its Tarp funds by the end of the year, though the company "will likely have to issue additional common equity in order to get regulatory approval" to do so.

The credit disaster in Florida hasn't dissuaded Fifth Third from considering opportunities to expand its footprint again, Kabat said, but it certainly persuaded him to never again allow such a large concentration of real estate loans.

Meanwhile he sees plenty of room for growth in existing markets, even in Florida, where the company has seen surprisingly strong deposit growth and now hopes to build up its commercial and industrial loan book.

The regrouping won't come without hiccups.

"We're not out of the recession yet, and there still are a lot of non-controllable, external environment things that have yet to come," Kabat said. "The market is in kind of a 'show-me' state. But I don't get overly concerned about that because you control the things you can control, and those are the things that I think eventually will be recognized."