-

A pair of North Carolina banks — FNB United and Bank of Granite — surprised industry observers last week, finding investors willing to commit $310 million for an arranged marriage between the struggling companies.

August 9 -

The Treasury Department has ordered board appointments to two banking companies that have missed dividend payments on its bailout investments.

July 21

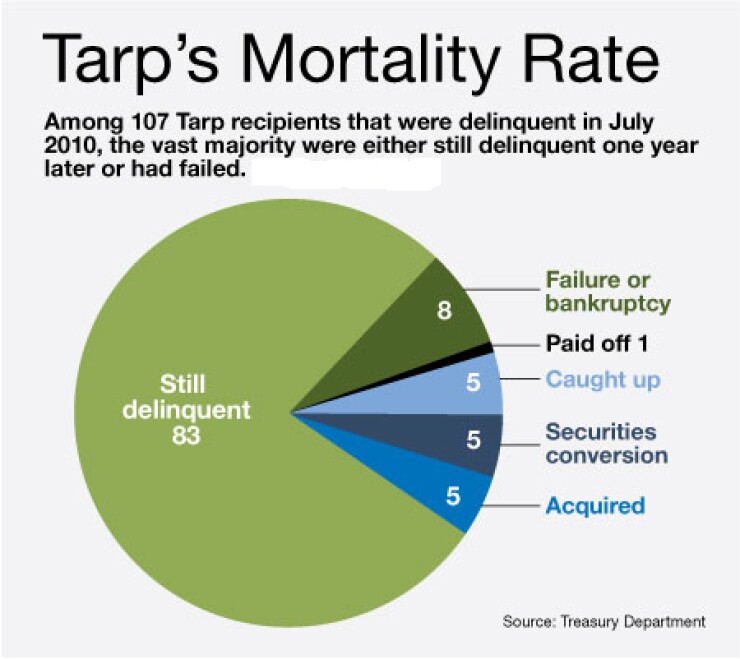

Like delinquent homeowners, banking companies that received rescue capital from the government and fall behind on payments have trouble getting out of the hole.

Of the 107 institutions that had missed at least one dividend on their Capital Purchase Program preferred stock by July 2010, almost 80% were still delinquent one year later. Eight among the group had failed by the time of the Treasury Department's

Five had been acquired in deals sweetened by partial forgiveness of amounts owed to the government, and another five secured conversions of government stakes into other forms of capital, generally in transactions that involved simultaneous equity infusions by private investors. Only five had fully caught up on late dividends and interest (others had caught up in part), and only one, Commerce National Bank in Newport Beach, Calif., had paid off its CPP preferred (see charts).

Moreover, an early stage of delinquency does not clearly imply better chances for recovery. Among institutions that were one payment late in July 2010, two had failed by July this year and most were still behind.

Lateness on CPP payments is usually accompanied by other stark indicators of stress. Most delinquent institutions are subject to consent agreements with regulators that restrict dividends, according to Brian Olasov, a managing director at the McKenna Long & Aldridge LLP law firm in Atlanta.

Still, the tally shows the ongoing nicks and cuts being absorbed by the centerpiece facility of the Troubled Asset Relief Program. (Almost all of the largest banking companies that received CPP infusions have exited the program, which is now above water. Dividends and other income exceeded securities outstanding, writeoffs and other losses by more than $3 billion as of August 10, according to the Treasury.)

Anchor BanCorp Wisconsin Inc., which has failed to make any payments since it entered the program in January 2009 and is still

FNB United Corp. in Asheboro, N.C., with almost $2 billion of assets, was also late as of the July report, but announced in early August that a $310 million private placement of common stock

Nonetheless, a thin record of recovery for institutions that have fallen behind so far suggests a tough road ahead for the group.