-

Citizens Republic Bancorp Inc. in Flint, Mich., reported a loss of $68.7 million in the first quarter, a marked improvement over the $106 million it lost in the last quarter of 2010.

April 28 -

The Cincinnati company, which has been squeezing better recovery values than expected from a wide array of bad credits, surprised analysts Thursday by announcing it had sold $228 million of residential mortgage loans and made $961 million of commercial loans available for sale late in the third quarter.

October 21 -

BB&T Corp. and PNC Financial Services Group Inc. were among those discussing Thursday how they are purging such assets at an accelerated rate, citing improved buyer interest and better pricing, particularly for residential development and mortgages.

July 22

For banks looking to sell nonperforming assets, pricing realities are not ideal. But they have become increasingly tolerable.

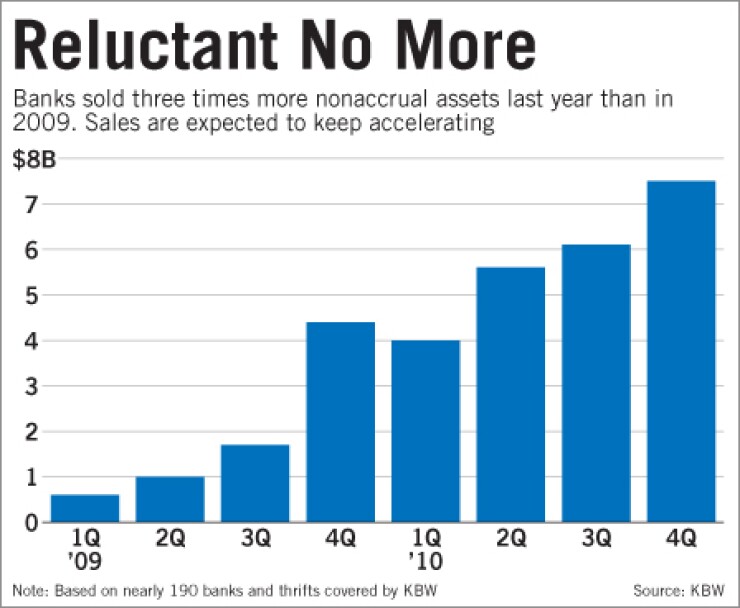

Sales of nonaccrual assets last year rose to $23.2 billion from $7.7 billion a year earlier, according to a review of about 190 banks and thrifts by Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. The early take on first-quarter results: more of the same.

What's changed, considering that banks are still taking sizable losses on many sales? The chasm that once separated banks' marks on nonperforming loans and realized sale prices has been shrinking. At the same time, healthier institutions are more capable of absorbing losses to extricate themselves from their nonaccrual portfolios. Though executives prefer to cite improved pricing — and not a prior aversion to taking charges — the two are often intertwined.

"Managements have had to be a little more realistic that their assets aren't worth par," said Chris McGratty, a KBW analyst who has been cataloging the steady increase in sales. "The other thing is that the banks are more willing to take the hit from a sale because they've raised capital, and they want to put the credit situation behind them."

Citizens Republic Bancorp of Flint, Mich., sold only modest quantities of bad loans until the fourth quarter, when it made $131 million in bulk sales. Because of the lower price such large-scale dispositions usually fetch, the company gives its special-loan officers a period of time to try to sell individual assets — and shunts the remainder into bulk sales if they cannot.

"Bulk sale is our least-preferred strategy because it takes the highest hit to us," Cathleen Nash, Citizens' president and chief executive, said on the company's fourth-quarter results call.

Another example of a bank that has ramped up its disposition activity is Fifth Third Bancorp of Cincinnati, which moved $574 million of nonperforming commercial loans into its held-for-sale account at the end of the third quarter. Since then, the account's balance of $680 million of commercial loans has fallen sharply, hitting $216 million at the end of the first quarter despite new inflows.

The assets' behavior has largely lived up to Fifth Third's marks, with negative valuation adjustments on the portfolio counterbalanced by $17 million of gains on loans that were settled or sold.

"Gains, losses and valuation adjustments have roughly netted out, and our marks still feel appropriate," the chief risk officer, Mary Tuuk, said on Fifth Third's first-quarter conference call with analysts.

Some banks got an earlier start than others. Among the large regionals, BB&T Corp. of Winston-Salem, N.C., was one of the earliest and most aggressive sellers, beginning a major disposition push in the second quarter of last year with a bulk sale of more than $500 million of nonperforming residential loans. It booked an $82 million loss.

In the third quarter, it took a $431 million loss from the sale of loans and the transfer of $1.7 billion of commercial real estate loans to its held-for-sale portfolio. It continued the sales through the fourth quarter and disposed of more than $500 million more in the first at rates commensurate with its current book values.

BB&T got such an early start, in fact, that it is now slowing down.

"Our plan right now would be a more one-by-one asset disposition to end-market buyers, and our experience for that kind of strategy has been a much lower mark," Clark Starnes, the company's chief risk officer, said on its first-quarter earnings call.

The flow of bad assets into the market may have been delayed by accounting standards that allowed banks to recognize losses on their own schedule, said Tom Selling, an accounting consultant and former professor at the Thunderbird School of Global Management in Glendale, Ariz.

In the process of estimating nonaccrual loans' value based on likely future cash flows, downside risks to an asset's pricing are generally ignored. And because the Financial Accounting Standards Board has allowed banks to ignore increased credit risk in those cash flows' discount rate, the resulting valuation is usually higher than a market-derived price.

The effect, Selling said, is to make valuations for nonaccrual loans less an estimate of what a bank could earn from holding onto them than a midpoint between the loans' original value and the price at which they will likely be disposed of. The rules function to "delay some loss recognition until the impaired loans are realized in fact," he said.

Either because of accounting practices or simply a natural lag for writedowns in a declining market, significant additional losses at the time of sale have been common.

"Incremental markdowns on NPA sales continue, albeit often more modest than on sales several quarters prior," the KBW report said. "That said, no uniform discount is able to be applied across the industry, in our view."

"I'm not sure the prices have gone up considerably, but nobody's pricing in as much uncertainty as they did a year ago," said Carl Streck of Mountainseed Advisors, which evaluated loans in connection with the $275 million recapitalization of Hampton Roads Bankshares in Norfolk, Va.

Far from being a sign of weakness, McGratty suggested, taking a bath on bad assets has become a sign of resilience. It is the entities still hoarding bad loans that are cause for concern, he said. Though pricing has improved, continuing to carry bad loans in hopes of still-higher prices is not much of a strategy.

"You can see some banks carrying problem assets at near par," McGratty said. "They'd love to sell, but they can't afford it. … Some asset classes, we see improved pricing. Relative to where we were, they're not at the bottom — but I'm not sure that I want to run my company that way. If I've got a bid and can move on, I'd rather do it."