-

The Florida bank is eager to add loans after raising $5 million to surpass capital requirements from a 2011 consent order. It did so at a time when capital raising is on the decline.

July 17 -

We'll know that the banking industry has returned to full health when we see a significant number of new charters. We're not there yet.

June 25 -

Many of these young banks are treading water, at best, waiting for the elusive rebound while coping with higher compliance costs.

April 13

Cool your jets.

That's what the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. is telling many de novo banks as they approach the upper limits of their previously stated business plans.

De novo banks, those open seven years or less, must file a change in business plans when they bump up against previously declared targets, expand into a new lending area, open a branch or make an acquisition. Regulators have amped up scrutiny after many de novos failed during the financial crisis. Survivors, many now healthy, want to expand but are barred from growing assets anywhere from 10% to 25% a year in some cases.

Some banks that have won amendment approval say it took nearly a year for it to happen. Ironically, those that have kept growing while awaiting FDIC approval have run the risk of violating their existing business plans.

"Most deviations occur when a de novo wants to grow and add product lines or business services," says Jeff Wilkinson, president and chief executive of the five-year-old Pioneer Bank in Texas. "That's the jam-up, period. When the business plans have to be signed off by the D.C. office … it could take up to a year."

"While it's pretty easy to submit a revised business plan, they'll beat you to death on it, and they'll leave it on their desk until the 11th hour," says another community banker who asked not to be named. "We can't do any mergers. We can't do any acquisitions. We can't do any expanded business lines."

The FDIC did not respond to requests for comment.

Since 2008, about 29% of the failures were banks chartered since 2000, says Michael Stevens, a senior executive vice president at the Conference of State Bank Supervisors. "It's natural and reasonable to expect the regulators to be a little more cautious."

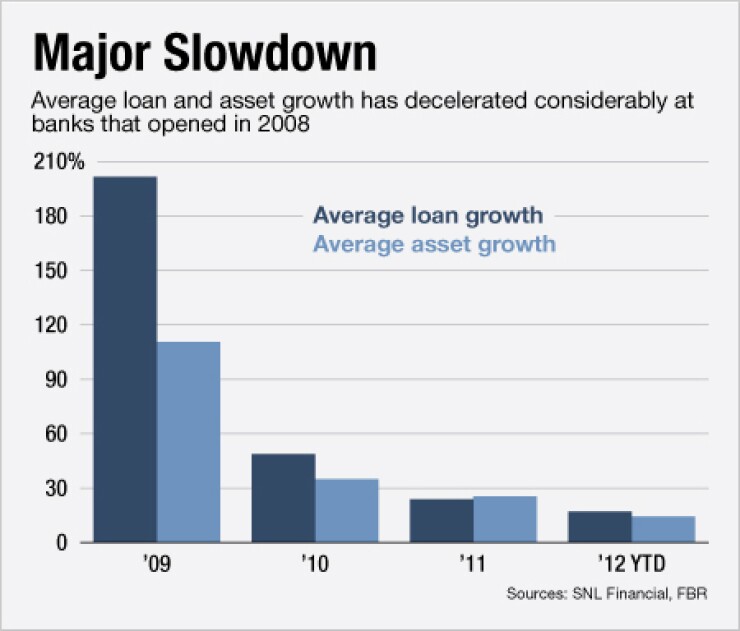

Young banks are tapping the brakes. The average annualized asset growth rate for the 95 banks that have

Most bankers agree that they should submit business plans and changes to regulators, given the high number of de novos that failed after diverting from an approved business plan. "I'm actually OK with the process," Wilkinson said. "But there needs to be some guidance issued as to their expectation and as to what is the time line."

Observers agreed bankers deserve more transparency and expeditious decision-making from regulators. "We've found that regulators are naturally suspicious of anybody growing substantially faster than their growth share within a market," says Walter Moeling 4th, a partner at Bryan Cave. "If you're growing 25% [annually] and everyone else is growing at 2%; are you really that much smarter than everybody else?"

Some de novo bankers, particularly those who recently regained financial footing, say maintaining regulatory relationships is harder now than when the banks were on life support.

"You wonder sometimes who your supporters are and who your detractors are," says Corey Coughlin, president and CEO of ProFinancial Holdings in Tallahassee, Fla.

ProFinancial's $70 million-asset bank was recently recapitalized after a complete management restructuring. Coughlin, who was brought in to turn the company around, says the regulatory relationship has been rocky despite a

"The feeling we get, frankly, is the FDIC is quite disappointed that we survived," Coughlin says, adding that his state regulator was supportive. "You'd think the regulators are working on some kind of unofficial law that they must reduce the number of banks."

Moeling says the approval process is better than it was early last year, when one of his clients waited more than a year to open a branch in a struggling market. The client went as far as providing testimonials and proof that its CEO knew the market.

"As someone once said of an examiner, 'I'm glad he's not my proctologist,' " Moeling says.

Younger banks have become more patient as regulators work through the financial malaise.

"We've had delays in some responses but you've got to be realistic in what [the regulators] going through," says Bruce Page, president and CEO of the four-year-old Intracoastal Bank in Palm Coast, Fla. Page says his bank has a "fantastic" relationship with its state regulator and the FDIC, largely because management is proactive reaching out to the examiners. "We don't wait for an annual exam. We call them regularly. We let them know that we want to be your star bank; we want you to not have to worry about us because you've got other problems out there. That's our goal."

The strategy seems to be working. Page says the bank's FDIC regional supervisor "intervened" to accelerate the bank's business plan through the powers at Washington. "We should expect for banks to be held accountable," he says. Regulators "have been great partners, we've gotten great ideas from them and they add value to our relationships. I know that might be very 'out there,' but I believe that."

What do you think? Are regulators justified to limit the growth of de novos, or should they be a bit more lenient? Leave a comment below.