Reliance Bancshares Chairman Thomas H. Brouster describes himself as a "turnaround banker," which certainly is apt since he has led 15 makeovers in his 45-year career.

Brouster said in a recent interview that the task of putting things right at the $1.2 billion-asset Reliance has been more difficult than any of his other reclamation projects. For one thing, the St. Louis company was virtually insolvent when Brouster

And then there was Tarp.

Reliance was one of the 707 financial institutions that received Troubled Asset Relief Program loans from the Treasury Department at the height of the financial crisis. Only 12 of them still owe Tarp money to the federal government, according to a Sept. 12 report to Congress, while an unspecified number of others — including Reliance — owe private investors who bought the debt. Its story serves as reminder that some banks still have not totally purged the past.

In 2011, two years after Reliance borrowed $42 million from Tarp, it quit paying dividends in an effort to conserve its dwindling supply of capital.

Brouster fixed Reliance's capital shortfall by leading

"It wasn't that we didn't want to deal with it," Brouster said. "We just thought we had to put it on the back burner while we completed the turnaround process, rebuilt the bank, rebuilt earnings and rebuilt equity."

A common-sense strategy — though it meant Brouster and his management team had to grit their teeth and watch Reliance's Tarp exposure climb higher and higher. In February 2014 the dividend rate on the biggest traunch rose to 9% from its original 5% rate.

"Every day when we came in here, it was almost like we felt we were working for someone else," Brouster said. "When you look at our rate of return and what we're trying to earn on a year-to-year basis against the [Tarp] rate, that's pretty tough. That weighed on us every day."

Not for long.

Brouster and his team are breathing easier since paying the $20.1 million in back dividends that had accrued the past five years this month. Better yet, Reliance expects to begin attacking the principal next year with an eye toward eliminating it in three years, Brouster said.

The Treasury Department had auctioned Reliance's Tarp bonds to private investors in August 2013. The bank was among a handful whose debt was sold at par value. As dividend checks were being cut this month, Brouster called each investor personally with the news.

"I feel really good about the fact we were able to fulfill our obligation on the back dividends and we'll be in a position to ultimately retire the whole thing," he said. "It's a big event for us, I think, a milestone for the bank and the holding company which frankly we're pretty proud of."

Reliance was able to make its dividend payments after securing two lines of credit totaling $40 million from Midwest Independent Bank, a Jefferson City, Mo.-based banker's bank with which Brouster and his principal associate, Gaines S. Dittrich, have had a longstanding connection.

"What we did in essence was draw about $22 million against the $30 million line," Brouster said. "Of that $2 million was kept as cash at the holding company and the $20 million — actually $20.144 million — was used then to pay all the back dividends to all the Tarp holders."

Naturally, the new debt carries "a much lower rate" than the 9% Tarp coupons, according to Reliance, which declined to give the exact figure.

A spokeswoman for Midwest Independent Bank did not return a reporter's calls.

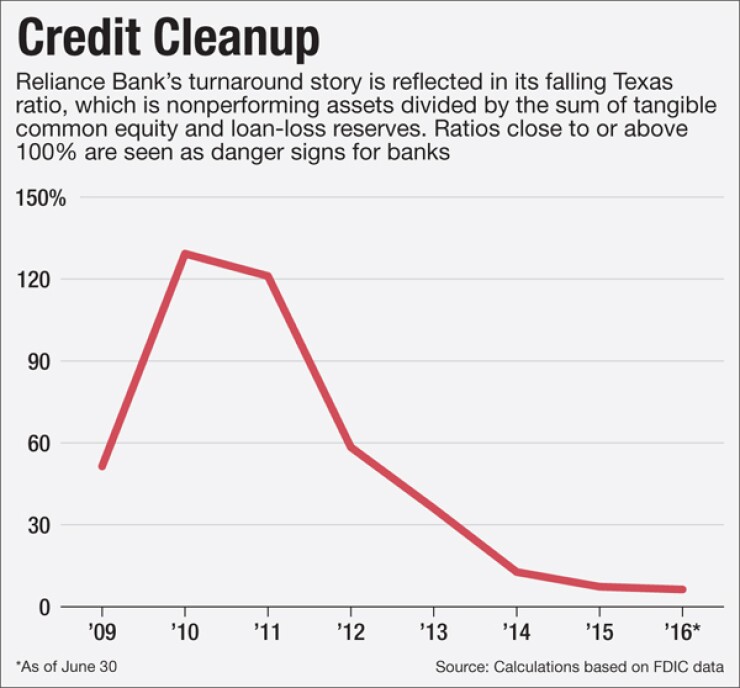

Ironically, Brouster said Reliance received no benefit from its borrowed Tarp money. Most, he said, was funneled into commercial real estate deals that fizzled and contributed to the epic meltdown the bank experienced between 2009 and 2011, losing $83 million, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

"It was expected to lose about another $11 million in 2012, at which point it would have probably lowered the capital level to a distressed number that would in essence have meant insolvency by the end of the year," Brouster said.

Reliance reported a profit of $7.1 million through June 30, and Brouster is projecting earnings of $15 million for all of 2016.

As impressive as that turnaround appears, the formula behind it was tried and true, rather than innovative. Brouster and Dittrich, who serves as vice chairman and chief credit officer, refocused Reliance's operation on St. Louis,

"We worked with borrowers one on one," Brouster said. "Not with attorneys to put things in default, but keeping the borrowers in their projects and properties as best we could so that we could end up win-win. "The last thing the bank wants is somebody's collateral. That's kind of how we operate."

As problem loans were shuttled off the books, they were replaced with performing loans to new customers, many of whom had followed Brouster and Dittrich from bank to bank over a number of years.

"I think in a community bank, relationship banking is still the key," Dittrich said. "Tom grew up in this community and has lived here his whole life. We've just built relationships with all of his banks through the years to the point that there are people out there we can call on that we know and know everything about their background; they know us. The relationship is there and that helped us build and grow after we got the bank cleaned up."

The formula appears to be working. Reliance has gone more than four years without reporting a loan past due 30 days.

Of course, pristine asset quality is nothing new for Brouster and Dittrich. "If you go back and look" at the last bank Brouster ran, Pioneer Bank and Trust in St. Louis, "I think we had 12 years of no past due over 30 days, and at [the bank] before that it was a little over five years," Dittrich said.

Brouster attributed much of the bank's asset-quality success to a simple but crucial tactic. It asks for its money.

"I know it sounds like small finance dealings, but in essence we call our customers five days after the due date if they haven't paid the loan on time — most of the time we don't have to make any calls."