WASHINGTON — While the energy sector and regions that rely heavily on oil and gas production have been hit hard by the glut in the global oil supply and the closure of drilling rigs across the country, the probability of widespread bank failures as a result appears to be remote.

That's because banks have avoided becoming hyperleveraged in the sector and have built up substantially more capital to weather prolonged low prices, according to analysts. At least some of that is attributable to capital and other reforms that were put into place since the 2008 financial crisis.

"For the largest U.S. banks, energy exposure is in the single digits, and even for the most concentrated banks that we rate, total energy exposures may be equal to their capital base," said Allen Tischler, senior vice president of the financial institutions rating team at Moody's Investors Service. "So if you compare that to the last big concentration risk that that sector has had to deal with, which was the commercial real estate [boom] several years ago, that was a multiple of capital for a whole number of banks. It's an issue a lot [of banks] are grappling with, but in terms of being widespread, it's just not big enough … a risk at most of the rated banks."

-

Credit risk, interest rate risk and cybersecurity concerns pose growing risks to banks in the first half of 2016, according to a semiannual risk report issued Wednesday by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

December 16 -

Federal Reserve Board Gov. Daniel Tarullo updated a Senate subcommittee on a pending proposal dealing with banks' commodity dealings that one lawmaker called "long overdue."

November 21 -

Federal Reserve Board Gov. Daniel Tarullo updated a Senate subcommittee on a pending proposal dealing with banks' commodity dealings that one lawmaker called "long overdue."

November 21 -

A Senate report released Thursday reveals new details about the role certain banks played in the physical commodities markets, specifics that lawmakers say supports the Federal Reserve Board's plans to restrict bank participation in that area.

November 19

The Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. declined to comment for this story. But Fed Chair Janet Yellen told Congress this week that the energy sector was "hard hit" and that the impact on broader economic activity and bank lending standards is a trend that regulators will have to investigate further — some of her strongest comments on the subject to date.

"We're seeing massive cutbacks in drilling activity, and that's rippling through to manufacturing generally, where output is depressed," Yellen said. "It's really those kinds of trends that we need to evaluate."

But banks have had warnings from regulators to be prepared for a downturn. The OCC in particular has been vocal about the potential for oil prices to slide and cautioned banks as early as 2014 not to be too leveraged. In April of that year, the agency issued a handbook directed at providing "guidance for bank examiners and bankers on the risks presented by oil and natural gas production lending activities."

Those warnings were prescient. Slowing demand for oil from emerging markets like China and India, as well as increased production from oil-exporting countries like Saudi Arabia, Libya and Iran, has led the average price of seaborne crude oil to fall from around $110 in July 2014 to around $30 in January, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That slump in prices has forced a substantial portion of the domestic oil producing industry — particularly high-cost producers that rely on hydraulic fracturing to retrieve oil and gas — to slow production or even close their doors.

Markets, regulators and the banks themselves have been watching the sector for signs that the emerging credit risk associated with loans made to those producers will be the root cause of a broader economic slowdown.

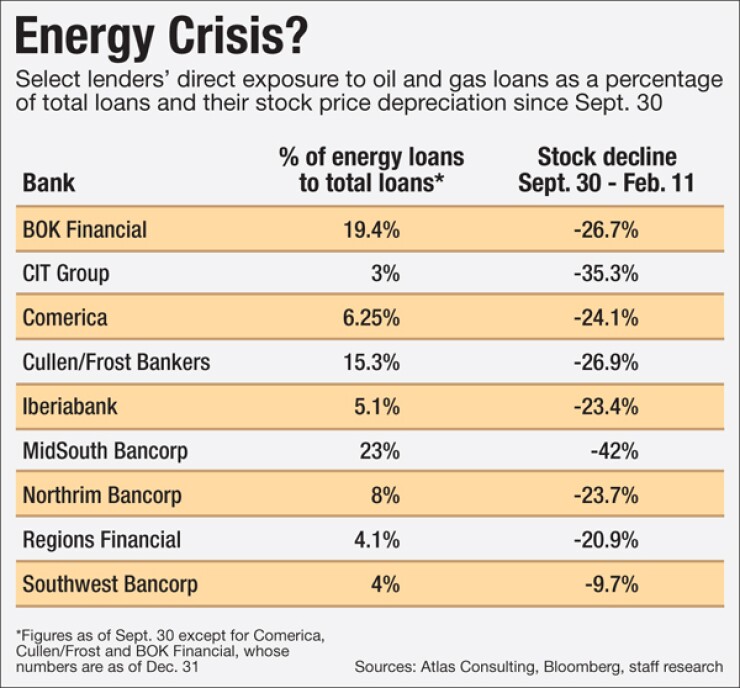

Moody's assigned negative outlooks to five regional banks — Amarillo National Bank, BOK Financial, Cullen/Frost Bankers, Hancock Holding and Texas Capital Bancshares — in October based on the firms' concentrations in the energy sector or in regions heavily reliant on energy production.

Goldman Sachs said in a January analysis of public disclosures by the largest banks with energy portfolios — including Bank of America, Citi, Wells Fargo, PNC, Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase — that those institutions appear to be building reserves "in the high single or low double digits" over the next year or two to offset losses from oil and gas exposures.

Several publicly traded banks with heavy exposures to oil and gas production have faced profound slides in their stock prices since the beginning of the year on fears of dwindling returns on energy investments. Regions Bank, which controls more than $123 billion in assets, has seen its stock price drop from $9.44 on Jan. 4 to close at $7.09 on Feb. 11. CIT Group, with more than $65 billion in assets, has seen its stock value fall 35.1% over that same period. Smaller banks like MidSouth Bank, a roughly $2 billion-asset bank based in Louisiana, and Northrim Bank, a $1.5 billion-asset bank based in Alaska, have also seen substantial declines in stock price since the beginning of the year.

But a weakening energy sector and losses by banks appears unlikely to add up to mass failures. Dallas Salazar, CEO of Atlas Consulting, said that the only real systemic risk that the energy bust poses to the broader financial system is if a major energy player defaults, and the risk in that case is based on the amount of debt that creditors would have to write off and the number of credit-default swaps that would come into play.

"Right now that domino is wobbling — it's not tipping over, but it's wobbling and we're seeing that in credit default swap pricing for these banks," Salazar said. "I don't think, unless it's CDS-driven, that we see any bank failures. The Fed is right — way better capitalization now, way better risk management."

But Salazar warned that even if banks don't fail, the fallout of 10% or even 5% nonperformance from some of the distressed banks will be a challenge, especially considering the role that energy investment played in the still-weak post-crisis economic recovery.

Energy commodity prices are notoriously volatile, making lending inherently risky and thus high-yield, Salazar said. For many banks, energy investment during the shale boom was a place where they could get sizable returns while still feeling safe. But now that we have entered the downside of the cycle, there isn't any other booming sector to take its place.

Bert Ely, an independent banking consultant in Alexandria, Va., said that whatever banks' ultimate exposures are or whether their loss provisioning is sufficient depends on how the economy performs in the next few quarters. Either way, we likely won't know for some time.

"We certainly are seeing loss provisioning for the year in banks that have energy exposures," Ely said. "Whether it's enough or whether they're looking broadly enough at their credit exposures, we won't know until a couple of years from now. The big question of course is whether this will cause bank failures, and I'd say it's too early to tell."

Energy lending is also highly regional. John Heasley, executive vice president and general counsel of the Texas Bankers Association, said that in his state the banking industry has been through this boom-and-bust cycle in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when declining consumption created an oil glut that hit producers hard and spurred a deep local recession. Heasley said banks and regulators kept that experience in mind and took steps to retain capital and diversify their portfolios.

"Compared to the 1980s, banks in the Texas oil patch are far more diversified in their portfolios than they were 30 years, ago, and that's been augmented by the experience of the regulators in that environment as well," Heasley said. "I think the capital situation is very healthy in Texas … yes there are some concerns, but it's a far cry from what it was in 1988 and 1992."

Aaron Klein, director of the Bipartisan Policy Center's Financial Regulatory Reform Initiative, said that part of the credit for that diversity and capital is due to the fact that banks are simply bigger and more consolidated today than they were 30 years ago. Bigger banks are naturally more regionally diverse as well as economically diverse, he said.

He said banks in Texas, Oklahoma and Alaska may be better prepared given their past experiences with downturns, but it's less clear whether other areas are ready.

"Rarely are the same people affected by the same crisis from the same appreciation in asset prices. You will never see Dutch banks overly extended in the tulip market," Klein said. "The bigger question is in North Dakota or Pennsylvania, one might expect to see more problems in their banking industries."

Keith McGregor, a partner with the global consultancy Ernst & Young, said there are reasons to expect that the worst may be still to come for producer defaults — and, by extension, bank losses. Most lending that is extended to producers is what is known as "reserve-based lending" — that is, a loan where the collateral is the reserves of the material that the company intends to extract.

RBL loans are generally reassessed semiannually, in October and in April. The assessments that were made last October were fairly mild, McGregor said, with banks assessing reserves at around $50 per barrel rather than the current $30.

"You're beginning to see the Chapter 11 filings picking up, and even in the past few weeks there's been a significant increase in the noise in the system around near-default or default situations," McGregor said. "Most people expect that the April redetermination will result in more severe facility reductions, and some companies are positioning ahead of that."

There are other reasons to be pessimistic, McGregor said. Because demand for crude is so low, producers are spending less time and money exploring for more oil, and less reserves means less reserve-based lending, which means less cash on hand.

Many producers also hedge their exposure to fluctuating oil prices by agreeing to sell at a specified price for a specified length of time. But as the second year of sub-$100-per-barrel oil approaches, more consumers of crude are willing to buy on the spot market and are not willing to lock in a price. The few producers that were locked in to more favorable prices up to now are reaching the end of those sales agreements. That could force some marginal producers to shut down.

Salazar said that the post-crisis actions by the Fed and other bank regulators to increase capital and step up supervision have unquestionably led to a more stable banking sector. But that doesn't mean that the sector, particularly in energy-producing regions, won't have to retreat in the coming months.

"What the Fed has done, the structural changes that have been made to banks, have insulated the country from seeing bank failures," Salazar said. "That doesn't mean we won't see bank [branch] closures. Even if we don't see failures, the 'oil economy' is still going to be slower. We're already seeing that."

But Klein is hesitant to give regulators too much credit. Whatever regulators' proactive actions in capital retention and diversification since the crisis, the Fed in particular has been reluctant to appreciate the decline in energy prices as anything more than a temporary problem, or one that has an equal upside for consumer spending. That is because the Fed's economic models treat the world's oil-exporting countries like any other producer of goods — a maximizer of profits — and fails to appreciate the geopolitical significance of oil and the noneconomic factors that have an outsize influence on its price.

"This is not the invisible hand at play," Klein said. "So just like with housing prices, where the economic models consistently got it wrong, I'm very concerned that bank regulators' overreliance on an economic viewpoint on the price of oil resulted in their inability to see this collapse coming."