The industry's got a thing for commercial loans, but it's still an open question whether that's a healthy attraction for banks.

It is unmistakable that commercial lending is where midsize banks seek to be right now. Banks of all sizes are

Banks are clearly in love with the growth potential of the commercial-and-industrial loan category. Before the onset of the financial crisis, at the end of the second quarter of 2008, C&I loans made up 18.52% of the industry's total lending. At June 30 this year, C&I loans had jumped to 21.4%.

-

The banking industry continues to sit on a mountain of problematic loans seven years after the onset of the financial crisis.

September 24 -

Synovus Financial struggled along with its customers during the financial crisis. Now that it's healthy again, it credits the strong ties it built with those customers, and the involvement of its executives in the communities they serve, with helping restore its status as one of banking's most reputable brands.

June 27 - Washington

Delinquencies on non-owner-occupied commercial real estate loans ticked up in the first quarter after years of steady declines. Some are shrugging off the increase, saying it was expected given the strong demand for CRE loans, but others say there's good reason to be concerned.

June 14

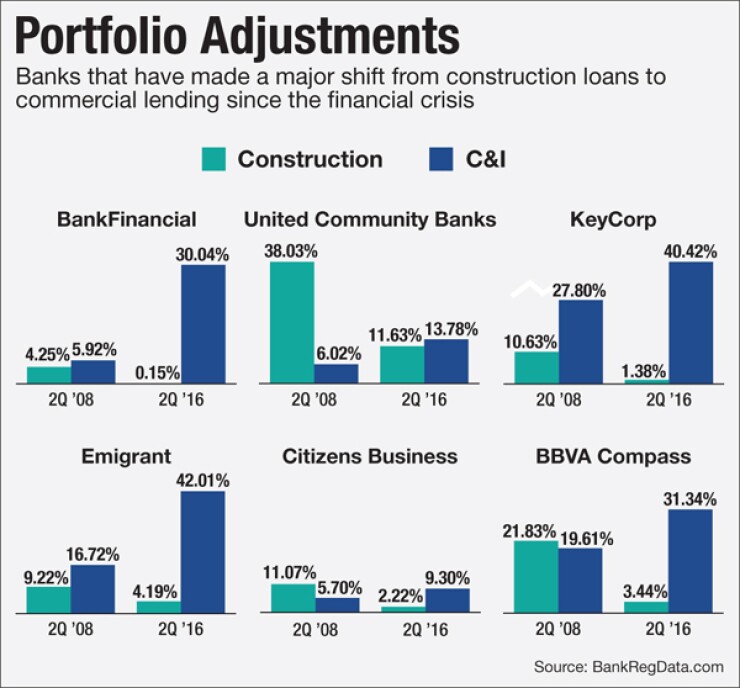

To a large extent C&I loans have filled the void created by the abandonment of the construction loan segment. At March 30, 2009, construction loans were 7.31% of the industry total. At the close of this year's first quarter they had fallen to 3.18%.

Dozens of institutions, of varying sizes and in every geographic region, have trod this path, downshifting on their exposure to construction lending while pouring capital into commercial loans.

The $29 billion-asset Synovus Financial in Columbus, Ga., is a prime example. It has

But it is a legitimate question to ask whether this a good shift, according to several analysts and investors. Yes, construction loans were the source of problems for many institutions, especially community banks, said Chris Marinac, an analyst at FIG Partners.

"The concentrations in construction loans got us in trouble, and when it went south, it became a domino effect for the industry," Marinac said. "That indigestion could have been avoided if we'd had more diversity in lending."

But commercial loans present their own set of risk factors, some of which are more concerning than those of construction loans, which are tied to an underlying piece of property.

"With real estate investments, the collateral is tangible and it's something that can be repurposed," said John Crowley, a portfolio manager at Eaton Vance who manages $11 billion, of which about 30% is in bank stocks. "You can hold it for longer periods of time and it's possible to recover some of your investment."

Commercial loans, on the other hand, present the real possibility of a total loss.

"If a C&I deal goes bad, it can be a total disaster," said Jon Winick, chief executive of Clark Street Capital in Chicago, which advises banks on the valuation and sale of loan portfolios. "The losses can be nearly 100%."

That does not seem to be worrying too many bankers for the time being.

"You have some banks that have pulled back and said, we're not going to compete maybe in this arena or area of construction — acquisition and development, for example — and maybe they are pricing it a little differently or just completely pulling back," Dan Rollins, chairman and CEO of the $14 billion-asset BancorpSouth in Tupelo, Miss., said on Aug. 3 at an industry conference.

The pricing issue concerns many investors. Many banks probably got too aggressive in building their energy loan books ahead of the most-recent downturn in the oil and gas sector, Crowley said.

"In order to get share, the pricing competition has been fierce and it makes me worry that the credit standards aren't as high as they should be," Crowley said.

Not every C&I loan that goes bad will produce 100% losses, but the loss rate on nonperforming C&I loans is significantly worse than construction loans, especially if a company goes out of business, Marinac said. Loss rates on C&I loans can range between 60% and 80%. Construction loan losses range from 20% to 30%, he said.

That is why banks need to "have a level of expertise" before they venture into the C&I space, since it's "not something that every bank understands," Marinac said.

"I get a little concerned that community banks don't have the talent and muscle necessary to do the credit analysis you need for commercial loans," Crowley said.

Commercial loans have a lot of merits, however, and it's understandable why many bankers are itching to do more C&I loans, said Brant Houston, a managing director at Atlantic Trust Private Wealth Management in Denver, which has about $28 billion in assets under management, including bank stocks.

"I probably prefer C&I loans to the construction category as long as [the loans are] backed up by cash flows," Houston said. "They tend to be less speculative than construction lending, where the cash flows can be months or years into the future before they kick in."

Many banks simply don't like the opportunities they find in construction loans today. The $8.3 billion-asset Citizens Business Bank in Ontario, Calif., has raised its C&I lending to 9.3% of its loan book at June 30 from 5.7% in the second quarter of 2008; and it's cut its exposure to construction loans to 2.2% from 11.1%.

"We don't think we are getting returns in construction lending we would like to get to warrant a higher concentration in that area," Chris Myers, Citizens' CEO, said on Aug. 2 at an industry conference. "We simply are not seeing the fees and the pricing that we would like to see there to really go after that."

Regional banks have also benefited from the expansion into commercial loans, Crowley said. As the category has become more popular, many regional banks in the Midwest, Southeast and other sections of the country have been able to recruit commercial loan talent from big New York banks, Crowley said.

"Maybe you have to take a haircut on your pay, but in other ways, this has really helped the regionals, disproportionately to the detriment of the money-center banks," Crowley said. "It's leveled the playing field for regionals."

Ultimately, bankers are like lemmings and right now everyone is moving to commercial loans, Winick said. Investors have to hope that the industry gets it right this time around.

"Banks tend to be the last one in the pool," Winick said. "They tend to follow the herd and sometimes that leads you in the wrong direction."