We don't need to keep skin in the game, since we were never in the game.

That's the central argument in a federal lawsuit challenging rules that require managers of collateralized loan obligations to retain a portion of the risk in their deals. If oral arguments at a hearing last week are any indication, this line of reasoning might carry some weight with the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington.

Collateralized loan obligations pool below-investment-grade corporate loans, slicing them into securities with varying amounts of risk and rates of return. Unlike lenders that securitize their own auto or student loans, CLO managers aren't in the origination business. Instead they acquire the collateral for their deals, either when the loans are issued or in the secondary market.

-

The company recently created a collateralized-debt obligation backed by bank debt, bringing to mind the types of structured investments that plagued smaller banks a few years ago. This time, StoneCastle will hold all the credit risk, instead of selling it off to banks. The CDOs are backed by relatively straightforward sub debt rather than hybrid securities.

November 2 -

It could take six months or more before people who deal in collateralized loan obligations receive more explicit regulatory guidance on "skin in the game" rules.

September 21 -

The Treasury Department launched an inquiry into the marketplace lending industry on Thursday, seeking information on its business models, customers and whether such firms should be forced to keep some "skin in the game."

July 16

The Loan Syndications and Trading Association's lawsuit hinges on this distinction. The trade group argues that a rule requiring sponsors of securitizations to hold 5% of the economic interest of these deals unfairly penalizes CLO managers, which do not engage in the "originate-to-distribute" model of lending that the rule, enacted under the Dodd-Frank Act, was designed to curb.

The lawsuit asks the court to vacate the risk-retention rule as it applies to CLOs backed by loans acquired in the open market.

During oral arguments at a three-judge panel Friday, senior U.S. Circuit Judge Stephen F. Williams studiously grilled a senior attorney for the Federal Reserve Board on the distinction between the roles of a CLO manager and an originator that issues securities backed by its own loans.

"They [banks] are originating to distribute. Now, the manager here is different. There is some overlap in legal interest, but it's different from the loan-generating banks," Williams pointed out in an audio file released by the court.

"Only in a narrow respect, your honor," replied Fed senior counsel Joshua Chadwick, noting that a manager is "serving the same purpose" as an originator, to offload risk to investors, whether acting as an in-house arm of an investment bank or as an independent firm.

"You weren't saying these risky loans are ever on the balance sheet of the manager?" Williams asked. "I'm not sure that makes a big substantive difference, but there is a difference."

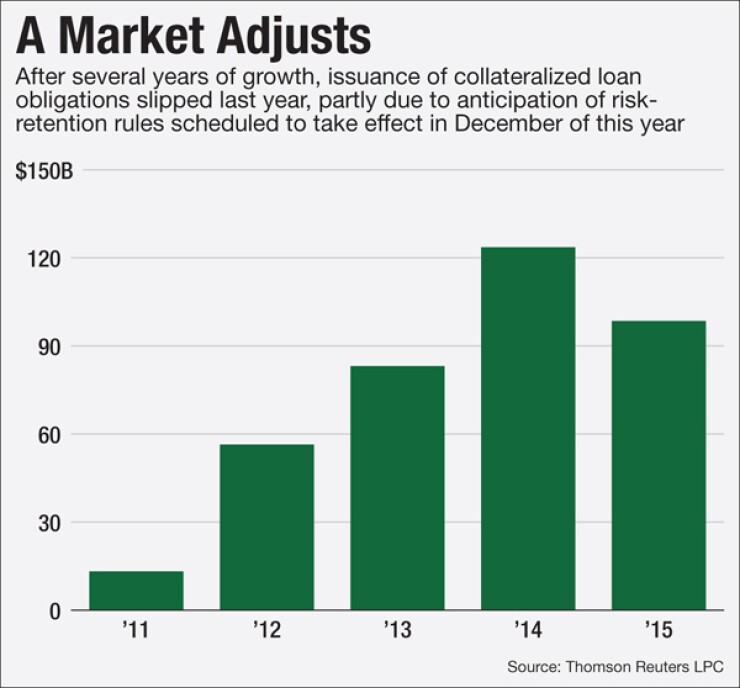

The risk-retention rule is scheduled to take effect for CLOs in December. But the court is not expected to decide on the trade group's suit before this summer, and that is only if the court ultimately determines it has sufficient jurisdiction. The court could decide to remand the case to the District Court level for a hearing.

CLO managers aren't waiting around to find out. The rule, which would require the sponsor of a $500 million deal to hold $25 million on its balance sheet, is considered so onerous that investors are loath to participate in deals from small and midsize managers that haven't demonstrated their ability to comply.

Even some of the largest managers are exploring alliances with firms that have deeper pockets. In January, CIFC Corp., which has $14.2 billion under management, said it had retained JPMorgan Chase as an adviser to explore a possible sale of the company.

In its filings with the court, the loan syndication trade group argues that federal agencies misapplied the term "securitizer" to CLO managers; it also argues that it is inappropriate to require managers to hold a 5% slice of the entire notional value of a CLO. Holding 5% of the riskiest securities issued by CLOs would be more appropriate, the group contends.

Before Friday's oral arguments, the parties to the suit had traded broadsides. In a briefing filed with the court in July, the LSTA charged the agencies with being "remarkably cavalier" about congressional intent in the statutory language of Dodd-Frank "and the actual rationales of their order."

The agencies have argued that the definition of "securitizer" includes players that directly or indirectly "transfer" assets and that CLO managers are transfer agents even though they never book the loans. The "LSTA's argument fails because it relies on an unnaturally narrow interpretation of the term 'transfer.' There is no evidence that Congress intended to bury such an exemption in the statutory definitions," the agencies have said.

In oral arguments, Richard Klingler, a partner at Sidley Austin LLP who represents the LSTA, urged the court to consider that a CLO is an "arm's-length" transaction with the CLO manager acting on behalf of investors.

The Fed's attorney "frankly was blurring the distinction between a balance sheet and an open-market CLO," Klingler said. "The crucial element here is the CLO manager acts essentially like an expert fund manager. They're not in the business of running a balance sheet. They're not in the business of originating loans."

Klingler was challenged by Chief Judge Merrick B. Garland, who took issue with the lack of clarity as to whether a CLO manager has control of loans that are first warehoused using a line of credit from an investment bank and then placed into an affiliated special-purpose vehicle.

"We have a lot of difficulty understanding … how the designation on somebody's books or [how] electronically the loan moves from the open market or from a bank to, through the manager … until the SPV is set up," Garland asked.

When Klingler acknowledged he could not answer "where the loans were parked," Garland deadpanned, "Neither do we."