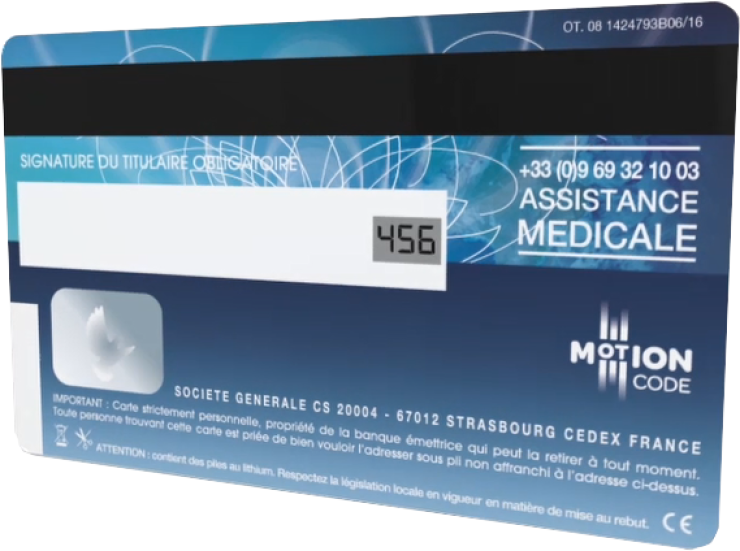

Last November, the French megabank Société Générale started offering its customers a debit card that features a three-digit security code that changes several times a day.

SocGen is counting on the battery-operated cards to help reduce fraud in the fast-growing realm of online shopping. Since the three-digit codes change frequently, criminals would need the actual plastic in order to pull off a successful scam.

The cost of the next-generation card: $13.30 per year.

For consumers, the value proposition behind the technology might seem dubious. In France, as in the U.S., consumers are not on the hook financially when their cards are compromised.

But Société Générale has been advertising the cards as a hassle-free way for consumers to achieve greater peace of mind at a time when cyberthreats are on the rise. And so far, the bank’s results have been impressive. The French bank said that it has issued close to 150,000 dynamic-code cards in last eight months.

“It’s extremely easy to sell the benefit,” Jean-Paul Albert, an executive in the bank’s card business, said in an interview. “Whenever there is a new innovation, if people see value in it, they’re prepared to pay for it.”

Now U.S. banks must decide whether to embrace the card security technology, which comes at a hefty price. One card manufacturer told American Banker that each card with a dynamic code costs $7 to $10 to make, depending on volume.

French consumers are more accustomed to paying an annual card fee than Americans are, and some observers are skeptical that a substantial number of U.S. consumers will be willing to pony up for the safer cards.

“They cost too much and no one wants to pay for them,” Avivah Litan, an analyst at Gartner Research, said in an email.

Banks reap certain benefits from the safer cards, even though the industry is not on the hook when compromised cards are used to make online purchases. For example, banks absorb the cost of reissuing cards when fraud occurs. In addition, some consumers may be less likely to use a particular card after it has been breached.

“While these cards have clear benefits to the bank,” Zilvinas Bareisis, a senior analyst at Celent, said in an email, “those have to be weighed against their usually relatively high costs.”

Meanwhile, banks have other methods to attack the fraud problem. Those steps include encouraging customers to pay with mobile wallets, where more sophisticated fraud management tools are available.

“Managing fraud risk is a difficult balancing act, because if you want to invest your limited amount of dollars to reduce the maximum amount of fraud, you want to focus your investment on those customers or those transactions that represent the highest risk,” said Randy Vanderhoof, director of the U.S. Payments Forum, a multi-industry group that focuses on payment technology.

Technology to make the three-digit codes on the back of cards more secure has been on the market for several years. But card manufacturers have recently started making a bigger push to sell the cards to banks.

The timing is partially due to the fact that banks have made substantial progress in their multiyear push to reissue cards with microchips, freeing up money and resources for other initiatives.

In addition, the rapid growth of e-commerce has lent more urgency to efforts to reduce online payment fraud. E-commerce represented

When credit cards get compromised, consumers typically have to jump through a series of hoops in order to get their house back in order, including contacting merchants that bill on a recurring basis.

“It’s a hassle,” said Garfield Smith, a vice president at OT-Morpho, which manufactures cards with dynamic codes for Société Générale. “The banks know that this can remedy that issue from the start.”

Smith said that his company, formerly known as Oberthur Technologies, is in various stages of collaboration with several U.S. banks. He expects the technology to be rolled out in this country before the end of the year.

Smith acknowledged that the $7 to $10 cost of manufacturing the cards may be an impediment to adoption, though he also noted that prices are expected to fall as production increases. The batteries in the cards last for approximately three years, assuming the code is programmed to change every hour, he said.

Gemalto, a Dutch firm with operations around the globe, also manufactures cards with dynamic security codes.

Paul Kobos, a senior vice president of banking and payments at the company, said that he is curious to see whether U.S. consumers prove willing to pay a fee to use the product. He said that banks may offer the cards to customers who regularly make big-ticket purchases online and therefore represent an outsize risk.

“I’m not sure it will ever be a complete mass-market product,” Kobos said.

SocGen sees the technology as having significant public appeal — the French bank noted that 9% of its customers who have bought cards since November have agreed to pay extra for the enhanced security measures.

“The product is extremely easy to adopt, as there is no change in customer experience,” Albert said.