This story is part of an ongoing series about the outlook for the second half of the year. Look for more coverage throughout the month of June. For prior stories,

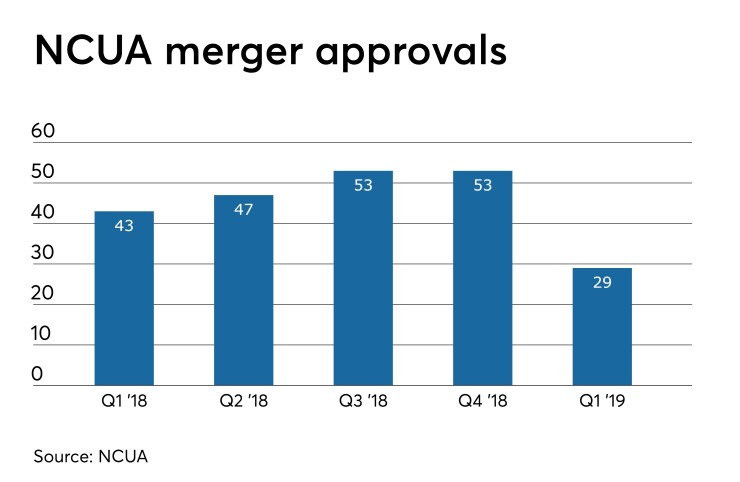

There’s uncertainty about whether a drop in credit union merger approvals in the first quarter means consolidation in the industry is slowing.

The overall number of deals could continue to decline as there are fewer credit unions than ever before and the time to get regulatory approval has lengthened. But consolidation will still continue to some degree, especially among larger institutions, as credit unions look for economies of scale to strengthen their ability to compete.

“Credit unions must get bigger to survive and prosper,” said Peter Duffy, managing director at Sandler O'Neill & Partners in New York. “And the larger credit unions, with their lower cost structures, are the ones that can compete better by offering lower loan rates, higher share rates and better fees while providing better digital delivery.”

The National Credit Union Administration approved 29 mergers in first quarter, down 45% from the number of deals approved in the third and fourth quarters of 2018. That’s also a decline of roughly 32% from the same period a year earlier.

There may be a few reasons mergers dropped off in the first quarter. First, mergers in the credit union space are likely to keep slipping in number partly because there are fewer credit unions – hence, fewer candidates for takeover, said Geoff Bacino, a partner at Bacino & Associates, a consulting firm.

The credit union industry has been consolidating at an annual rate of about 3% since the 1970s, said Glenn Christensen, president of CEO Advisory Group, a credit union merger and acquisitions consultancy firm based in Lake Tapps, Wash. There were roughly 5,330 credit unions at the end of the first quarter, down more than 3% from a year earlier but down less than 1% from the fourth quarter.

“I think this slowdown is part of a long-term trend but the decline in numbers of mergers will be gradual,” Bacino said.

Secondly, since the financial health of the credit union industry is “pretty good overall” there are simply fewer struggling credit unions seeking to merge out of existence, said Dennis Holthaus, managing director of Skyway Capital Markets in Tampa, Fla. That could be partly responsible for the decline in merger approvals.

However, Duffy, who advises on credit union mergers, thinks the industry is on the “precipice” of a wave of consolidation. The reason behind these deals are changing too. More institutions are making a strategic decision to merge and fewer are doing so because of financial distress.

Of the 53 mergers approved in fourth quarter, 43 occurred because one or both parties sought to expand their services, according to a CEO Advisory report. Only four occurred because one partner was in poor financial condition. In the past, Christensen noted, many mergers took place because one party was financially struggling.

Credit unions may decide to find a merger partner to gain economies of scale to better compete against fintechs, expand their geographic reach and become better equipped to deal with legislative and regulatory issues, sources said.

“One thing we are seeing is more credit unions, especially large-asset institutions, making merger deals purely for strategic reasons, not because they’re facing financial pressures,” Christensen said.

What deals will look like

While the overall number of credit union mergers may slip, the average size of these deals is increasing, said Vincent Hui, managing director of Cornerstone Advisors, a bank and credit union consulting firm. Hui believes the number of deals may drop off slightly or remain steady through the second half of 2019 and into next year.

Credit unions used to be satisfied when they reached $1 billion in assets but now many executives believe they need to become $5 billion in assets, Hui said. The larger size makes it easier to make investments to stay relevant and offer members a full array of services.

“I think we are seeing and will continue to see $1 billion-plus credit unions merging with smaller, but not too much smaller, credit unions,” Hui observed.

He cited the agreement for

“That deal really made people look up and notice,” Hui said. “It was two very large, well-run institutions merging – rather than, say, a strong credit union acquiring a weaker peer.”

Credit unions with under $100 million in assets will struggle to survive on their own, experts said. That’s likely to force some to merge with mid-sized institutions in coming years, especially if an economic recession hits.

“Unless small credit unions can find a niche membership to serve, they are facing a losing battle,” Bacino added.

Approval times slowing

It may take some credit unions longer to get their mergers approved. This can be especially true for larger institutions that are more complex, Hui said.

Dennis Dollar, a former NCUA chairman and now a consultant in Alabama, pointed to the NCUA’s implementation of new merger disclosure rule last year as a possible cause in the slowdown of merger completions. Approval times have lengthened from a few weeks to several months, Christensen said.

A new merger disclosure rule, which went into effect in October, requires that disclosures be sent out a minimum of 45 days prior to the merger being voted on. Under the prior rule, the merger meeting and vote could occur as quickly as seven days after the merging credit union mailed a notice of the meeting vote to its members.

“This is, naturally, making the process more elongated and slower to get mergers finalized,” Dollar said.