By nearly all accounts, credit unions came out on the winning side of

While the American Bankers Association is expected to take several weeks to decide its next steps, at least one observer expects the trade group to contest the ruling.

“I wouldn’t be surprised” if the ABA chose to appeal, Mary Dunn, an attorney with CU Counsel, a consulting firm in Washington, said Friday in an interview.

But, she added, “I have very serious reservations about whether they could win.”

The NCUA approved the field of membership rule in December 2016 and the ABA filed its suit challenging the agency’s action later that month. Two of the four provisions in the rule were

Dunn, who worked previously as general counsel for the Credit Union National Association, called the decision by a three-judge panel of the U.S Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia “highly significant, adding that there was little in the 38-page ruling with which bankers could be pleased.

“It was a pretty good win for the agency,” said Geoff Bacino, a former member of the NCUA board and a partner at Bacino & Associates in Alexandria, Va.

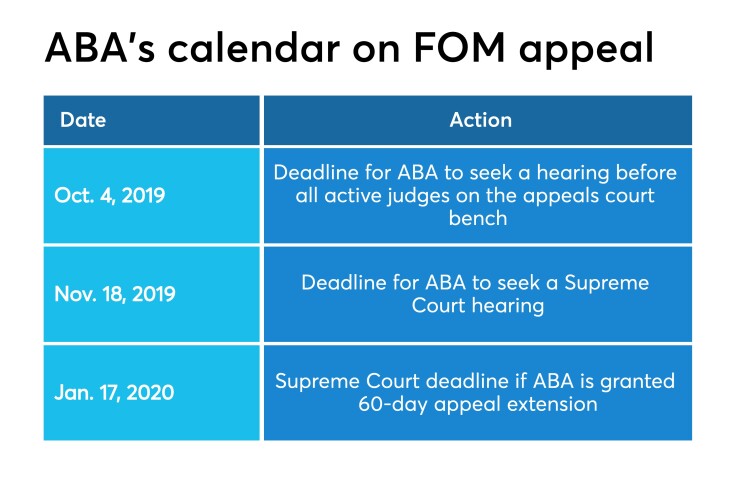

Speaking on background after the decision was handed down, an ABA spokesperson said the group is in no rush to weigh its options, noting it has at least 45 days to decide whether or not to appeal.

NCUA spokesman John Fairbanks said Friday that the regulator was continuing to review the decision and declined comment.

No slam dunk

The appeals court’s

“In this facial challenge, we review the rule not as armchair bankers or geographers, but rather as lay judges cognizant that Congress expressly delegated certain policy choices to the NCUA,” Wilkins wrote.

Following that line of reasoning, the appeals court overturned

The appeals court reinstated both those provisions but questioned a third one that would permit credit unions to use portions of a core-based statistical area to define their fields of membership while excluding the urban core.

Wilkins stated that he found “merit” in the ABA’s contention that rejecting an urban core might result in redlining. Even so, he did not vacate the relevant portion of Friedrich’s decision, which raised no objection to the practice. Instead, Wilkins returned the issue to the district court, instructing the NCUA to clarify its position.

“What did the appeals court want? They found [the provision] arbitrary and capricious basically because the NCUA didn’t explain it well enough,” Dunn said “But they didn’t vacate it. That’s really important. They sent it back for the NCUA to explain further.”

According to Bacino, “there’s no reason for credit unions" to redline, "and they don’t do it.” So, he said, the NCUA would have little difficulty “taking care” of the redlining question.

Dunn, for her part, said the task would be no slam dunk. “ABA did raise a point which has to addressed,” she said.

“It’s not redlining in the traditional sense” of denying credit to a particular class of customers, Dunn added. “It’s an issue of creating a community that would exclude people who would otherwise be included … NCUA has to explain why that’s not going to be the case.”

Keith Leggett, a retired ABA senior economist who publishes a blog focused on credit union activities, said the decision leaves banks free to challenge individual field of membership decisions, and that the results of any challenges could serve to establish a set of limiting parameters. Some such measures have already begun, at least up to a point, including legislation proposed earlier this year in Nebraska that would have

Wilkins concluded in his decision that the NCUA “possesses vast discretion to define terms” but that its authority “is not boundless.”

Leggett added that the decision’s treatment of the urban core issue amounts to a win for bankers — even if the provision is ultimately reinstated upon reargument.

According to Leggett, no credit unions have sought a field of membership excluding an urban core. It’s unlikely that one would do so now that the practice has been linked to racism.

Shifting views of Chevron

Like Dunn, Leggett believes it’s possible the bankers could appeal the decision, including going all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. And while some have suggested credit unions would do well there — Chief Justice John Roberts formerly advocated for the industry in the fight that led to the Credit Union Membership Access Act in 1998 — Leggett said larger shifts are at play.

“The big issue, if you’re looking at an appeal, is that the nature of the court is changing,” Leggett said Friday in an interview. “Several justices have raised questions about the Chevron doctrine. They have problems with matters they believe should be decided by Congress being ruled on by regulatory agencies. This could provide a challenge to Chevron."

Dunn agreed that the high court’s thinking about Chevron might be changing, but she said an appeal by the ABA would face difficulties under any standard.

The appeals court "considered the authority of the agency in the context of what discretion Congress gave it," she said. "I don’t think other [judges] have given that aspect the proper deference. … I think that was highly appropriate and the result was a decision that’s consistent with the Federal Credit Union Act.”