Credit unions are experiencing a CEO succession challenge unlike any other industry.

For years, the credit union industry has successfully served its members while offering consumers a viable alternative to traditional banks. Their conservative nature, along with the natural limits of growth that come with sphere-of-membership and select employee member rules, has led to an industry-wide culture steeped in traditional volunteer boards managing long-term CEOs and C-suite executives.

This structure and the relationships that have developed have stood the test of decades. The savings and loan crisis of the ‘80s, the internet boom of the late ‘90s and the Great Recession were all witnessed and survived by the senior management teams at most of today’s credit unions.

However, this invaluable industry knowledge and veteran leadership comes with a downside that is unique to the credit union industry. Russell Reynolds Associates’ recent credit union CEO searches have uncovered some unsettling

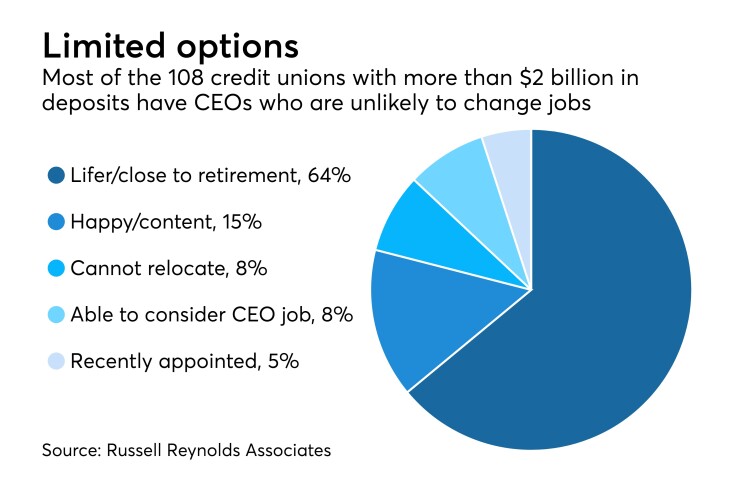

Of the 108 U.S.-based credit unions with more than $2 billion in deposits, 64% have CEOs considered near or at retirement age. Furthermore, another 15 percent are happy where they are with no intention of leaving, 8 percent cannot relocate for personal reasons and 5 percent have recently been appointed.

This leaves 8 percent of CEOs able to even consider an opportunity outside of their own credit union.

For most industries, these statistics would be cause for concern but not alarm.

Within traditional banking there are often a handful of direct reports to the CEO vying for the top role. Many of these executives have been in formal succession planning programs for years, honing their skills across sales, marketing, finance, operations and technology. They have gained exposure to boards, are technically competent across multiple skill sets and culturally ready to lead.

This is not a standard trend across the credit union industry. A majority of the nation’s credit unions have well-established senior executive teams whose tenures mimic that of their CEO. Furthermore, their skills are often steeped in a single discipline, such as spending decades in operations, sales or finance. Diversity in thought and experience is not commonplace.

This strength of credit unions – long-tenured executives – has unintentionally led to a dearth of executives ready to be a CEO in an industry about to experience a flood of retirements. Our studies show that more than 70 percent of credit unions above $2 billion in deposits have at most one qualified C-suite executive ready to take the helm.

This statistic is made even more daunting by the unique structure of select employee retirement programs (SERP) that dot the credit union landscape. These SERPs are expensive and difficult to buy out, thus making it nearly impossible to recruit those few CEOs or others in the C-suite who possess the skills to move immediately into a CEO chair.

We are approaching a retirement super-cycle with critically low viable successor ratios. These statistics and facts highlight the need for boards to prioritize the development of robust leadership succession programs.

It is our experience that credit union boards typically spend too little time on CEO succession planning and the ones that do tend not to go deep enough. A majority of credit union board members tend to be parochial in their reach and are challenged to refresh a list, if it even exists, to match the changing landscape and needs of their credit union.

Boards also have a tendency to lean toward weighing past experience too heavily, without adequately considering an executive’s style, cultural fit and ability to adapt to changing circumstances as key factors of success.

Our discussions with credit union boards and CEOs led to three common themes that are important to successful long-term succession planning.

First, boards that have developed formal succession plans must ensure they contain individually tailored development plans for high-potential internal executives. This should be complemented with a process that allows the board to compare external and internal talent.

Secondly, it is imperative that incumbent CEOs and boards take a longer-term perspective on succession planning, with the understanding that the plan is an ongoing process. Incumbent CEOs and boards should begin to identify and assess potential internal successors between three and five years ahead of the planned succession. This provides boards and the CEOs adequate time to give internal candidates opportunities that will allow them to develop capabilities and test their mettle.

Finally, boards must recognize the aggressively changing landscape that is today’s financial services marketplace and work to ensure the characteristics they define as must-haves for a CEO fit with this evolving reality. Credit union members’ expectations are changing at a rapid pace, as are the technologies powering their experiences.

While the above are best practices, it is important that planning is tailored to the culture of one’s credit union and other factors, such as succession timelines, growth initiatives and membership traits.

Whatever the succession planning strategy come to be, what it cannot be is inactive. Succession planning is a living process, a board-led initiative that challenges the CEO to work with their executive team to serve the needs of the credit union today and into the future.

Robert Voth co-leads the consumer and commercial financial services practice at executive search and leadership advisory firm