Perusing the trade press recently, I've concluded that I'm the only person in credit union land who thinks relaxing mark-to-market (MTM) accounting rules was a bad idea. But I have plenty of company in the international accounting and investing communities; the IASB, the AICPA and the CFA Institute (of which I'm a charter holder) adamantly opposed FASB's move.

Even FASB members themselves acknowledged they didn't like it, but that Congress held a gun to their heads. Ever the quipster, Rep. Barney Frank told the board, "It is important that we get some speed...You are the FASB... (not) the 'slowsby.'" Clever as it may be, that statement illustrates one of the problems with the move: it was a rush to judgment. We've seen recent examples where rushes to judgment urged by Congress have turned out badly. Remember the urgency of passing the TARP?

The defenses of relaxing or eliminating the rule - some of which were "supported" by very fuzzy math-unfortunately miss the mark. One noted that, after MTM was eliminated by the government during the Depression, we didn't have another such financial calamity until after MTM was resurrected, purportedly in 2007. The implication: SFAS 157 caused the current crisis.

The Two Problems

There are two problems with this notion. First, MTM actually returned in 1993, with SFAS 115. By and large, those subject to it didn't complain at the time-certainly not during the periods of falling rates since then, when bond prices soared and valuation adjustments were positive. Moreover, we didn't have a financial meltdown during that period.

Second-and this is the fundamental truth that many seem to avoid-this crisis was caused by financial illiteracy, excessive leverage, rampant real estate speculation, failure to recognize the fundamentals of supply and demand, relaxed lending standards, mortgage "innovations," further "innovations" in securitization, ratings agencies' failure to assess risk, and yield-hoggery on the part of many investors, who substituted "buying ratings" for due diligence.

It was this toxic brew that poisoned the patient, not an accounting rule. It's been stated that the strongest reason for eliminating MTM is that it's been blamed for causing financial institutions to fail. One could blame consumption of water for obesity, but that wouldn't be a good reason to do away with H2O. Baseless blame isn't good cause for rule changes.

Blaming MTM for the crippling losses that have resulted from the mortgage mess is like blaming the scoreboard for the Detroit Lions' having lost 16 games losses last season. Following the anti-MTM logic, the Lions are every bit as good as the Steelers -if we'd just based scoring on some other criteria than crossing the goal line or splitting the uprights, and Matt Millen would still be coachinggeneral manager.

Accountants and investors opposed relaxing MTM because it takes away two things that are (or should be) important to investors: integrity and transparency. The investment world is concerned-rightly so-that relaxing the standard could scare private capital away from banks, just when we desperately need to attract it.

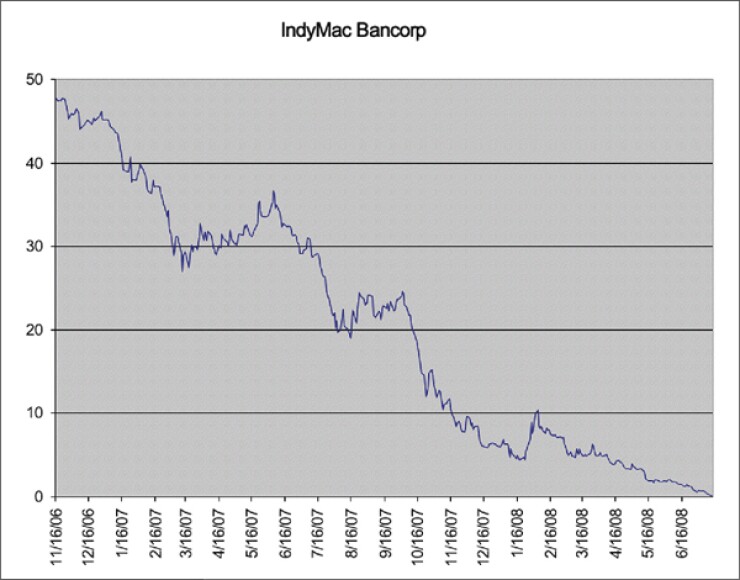

A simple graphic example explains why. The first graphic in the upper right of this article shows the stock performance of IndyMac Bancorp, the large California mortgage lender that was seized by the FDIC last July. IndyMac's stock was near $50 a share in late 2006, on strong earnings from record mortgage originations, primarily in hot California real estate markets. As the subprime debacle morphed into broad economic collapse, IndyMac's stock price gradually unraveled, before finally hitting bottom when the FDIC stepped in.

What drove the decline? Large unrealized losses, which were reflected in IndyMac's quarterly financials. What effect did that have? It provided early warning to investors, depositors and regulators that trouble was brewing.

Now, imagine a different world, without the transparency of MTM, where IndyMac could value its holdings as if delinquencies and defaults weren't rising. IndyMac's stock might have performed like the second graphic, perking along at the 2006 high-until the day the regulator closes the doors. Then, it free-falls to the post-takeover, pocket-change price. For those who remember the thrift crisis, this scenario should sound familiar.

As an investor, a depositor or a regulator, ask yourself this question: would you rather slide down a slope, or fall off a cliff? Or imagine yourself in the shoes of Henry Paulson or Ben Bernanke the week that Merrill, AIG and Lehman all went down, had there been no early warning.

The Chief Criticism

The chief criticism of MTM has been that current valuations are based on illiquid markets. The argument is made that the bonds are triple-A rated, and have paid as scheduled. This is somewhat inaccurate and misleading, and misses the point. Many bonds originally rated AAA have been downgraded to junk status. By now, we should all recognize just how accurate the original ratings were. If the ratings agencies supplied snipers to the Navy, the captain of the Maersk Alabama would still be a hostage, and there'd be three dead fish somewhere in the Indian Ocean.

When markets are illiquid, bonds are valued by discounting their expected future cash flows, not their past on-schedule payments. When the collateral is California HELOCs, the properties are in foreclosure, the support bonds have nearly evaporated, and the bond insurer is itself in default, the future cash flows are highly questionable. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Relaxing the rules also increases the risk of gaming the system-witness the NCUA's recent disclosure that WesCorp planned to use its own internal valuations rather than those of the independent firm it hired to value its portfolio, which would have understated its losses by $500 million.

MTM accounting is despised by those affected by it, either directly on their own balance sheets or indirectly through the balance sheets in which they're invested. So understandably, relaxing the rules brings them some relief, if only temporary. But in this instance, what's good for the goose may be bad for the animal kingdom overall.

Brian Hague is President/CEO of CNBS, LLC, Overland Park, Kan.