If the mortgage industry takes one lesson from the housing crisis to heart, it should be the danger in having loose definitions and broad classifications of loans.

Granted, labels like subprime, alt-A, midprime and superprime have been rendered virtually useless since the housing market bust; nearly all loans being made these days, and subsequently bought and sold in the secondary market, are ones that conform to the underwriting guidelines of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Housing Administration.

But mortgage experts believe such terms, particularly subprime, are likely to resurface once the securitization market is healthy again and investors have a greater appetite for risk.

"It's an industry where terminology has always been wonderfully nonstandard," said Michael Youngblood, founder and principal of Five Bridges Advisors LLC, a Bethesda, Md., asset management firm. However, "given these labels had wide currency for many years prior to 2008, I think that the industry will attempt to revive them, but revive them meaningfully."

That's the hope, at least. If and when subprime does return, mortgage professionals say there needs to be a more concrete definition of what exactly that means. The challenge will be better distinguishing between borrower risk and the risk of certain loan characteristics, which were often layered during the heyday of mortgage lending.

"The system fell down when all of these categories were willfully obscured and in many cases fraudulently obscured, when a midprime loan was simply a mispriced alt-B loan, and when an alt-A loan was simply a mispriced subprime loan," Youngblood said.

Regulators have begun to take up efforts to encourage prudent underwriting and provide more transparency for mortgage investors.

Last week, the Securities and Exchange Commission issued a proposal that would, among other things, require issuers to give greater disclosure of loan-level information. The SEC also is proposing that issuers wait five business days between the filing of a prospectus and the sale of any securities to give investors more time to analyze the loan data.

"The earliest steps to enter back into the marketplace do need a definition and clear understanding of the products," said Brian Hershkowitz, chief executive of Maximum Value Group, a mortgage industry consulting and advocacy firm.

The industry's desire for more clarity underscores the belief that subprime lending is not inherently bad. Most experts agreed that when the proper risk controls are applied, it can be done very well.

"The word subprime itself should not connote improper lending," said Bruce Krueger, senior mortgage expert at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. "But it should be followed by, 'What do you mean and how are the risks controlled?' "

Traditionally, the word subprime has been used to describe loans given to borrowers with poor credit.

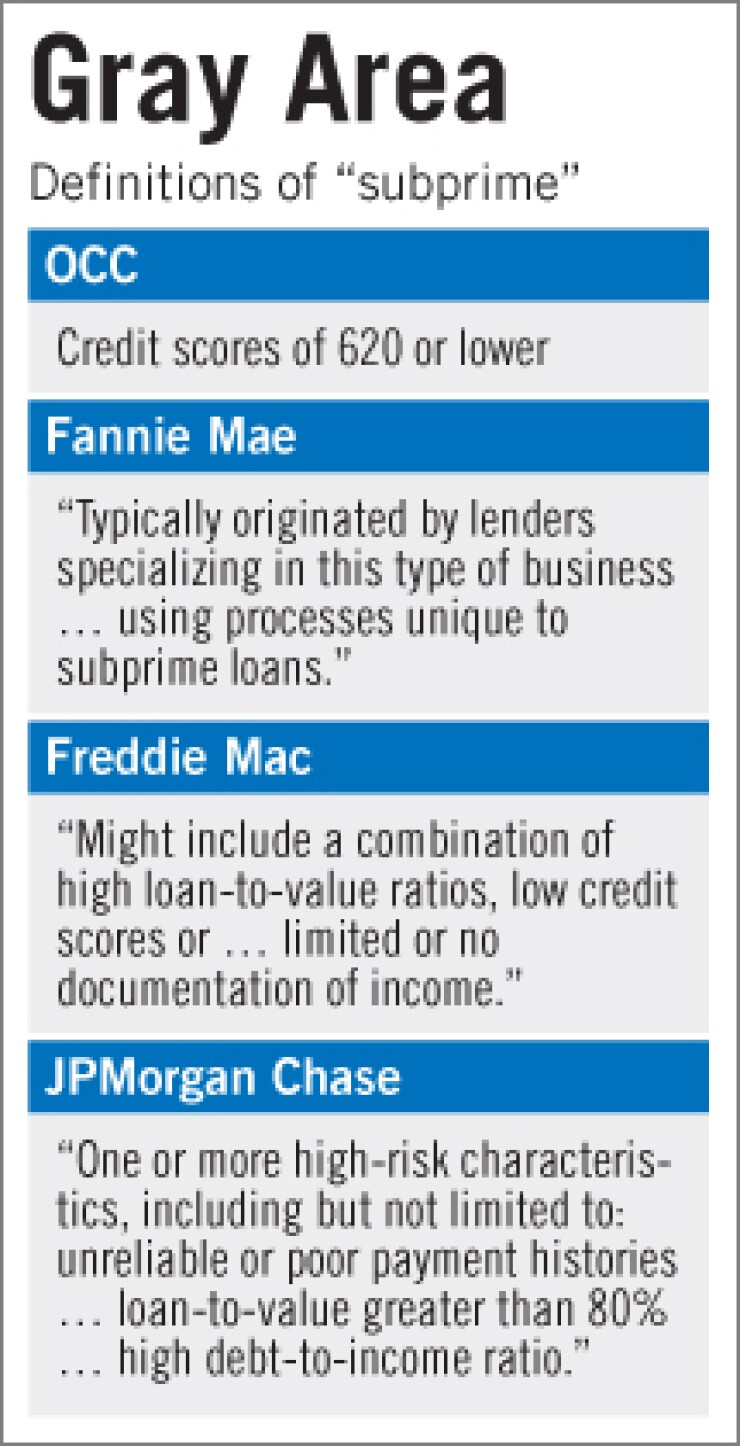

But there was never a concrete, industrywide definition, and lenders and other industry groups were left to adopt their own descriptions.

The OCC, for one, defines subprime and other loan types specifically by credit score.

Subprime borrowers are those with a credit score of 620 and below; alt-A borrowers have a score of between 620 and 659; and prime borrowers have a score of 660 and above.

JPMorgan Chase & Co., meanwhile, sees subprime loans as ones "designed for customers with one or more high-risk characteristics, including but not limited to: unreliable or poor payment histories … loan-to-value ratio of greater than 80% … high debt-to-income ratio … or a history of delinquencies or late payments."

Making things worse was the fact that plenty of borrowers with good credit histories were offered products with risky loan characteristics and inadvertently lumped into the subprime category during the housing market boom. Essentially, what encompassed a subprime loan not only varied greatly among organizations, but widened considerably during the previous decade.

Then there was the alt-A loan, the definition of which was also vague, but generally came to be known as a loan that fell between the subprime and prime categories and/or required little or no documentation of income.

In theory, alt-A was of higher credit quality than subprime, but the lines of distinction began to blur soon enough as lenders sought to classify loans as anything but subprime, despite their riskiness.

"There was some attempt by Wall Street … to say that alt-A was somehow better than subprime," said Paul Bossidy, chief executive of Clayton Services LLC, a Shelton, Conn., due diligence firm.

"As it played out, there was lots of bad practices in the alt-A crowd also. … So the losses taken were quite substantial, just like subprime."

Other labels emerged during housing's go-go years, including midprime, nearprime and superprime. Even a deviation of the alt-A loan was created and coined as "alt-B."

A July 2007 post on the blog Calculated Risk summed up the label du jour nicely: "The term 'alt-B' is not an attempt to describe a kind of subprime lending as much as it is a derogatory term for the worst kind of officially described 'alt-A.' … If it has any clear definition, it generally refers to the lowest-quality segment of the somewhat nebulous 'alt-A' world."

At Citigroup Inc., nonprime became the preferred term to subprime during the mid-2000s in the company's residential mortgage unit, according to recent congressional testimony from Richard Bowen 3rd, a former head underwriter. The terms inevitably became inadequate to describe the inherent risk in the product, making it difficult to price the loans appropriately and sell them in the secondary market. As Howard Glaser, a former Department of Housing and Urban Development official who now runs his own consulting firm, put it: "The subprime loan was in the eye of the beholding investor."

"Today, these labels are all gone," Bossidy said. "We still hear them … but there's no meaning to it."

The problem is, there never was.

"The one wave we all got caught up in," he said, "was the notion of relying on these labels and assuming it meant something with regard to the underlying loans."