-

Underlyling the FDIC's relatively positive quarterly report is a story of risk aversion by banks. Earnings can't be sustained at this rate, regulators warn.

August 23 -

The Federal Reserve's vow to keep interest rates low for another two years has taken a number of bankers by surprise.

August 12 -

Faced with an influx of money that could stream out as suddenly as it arrived, banks are being forced to maintain big pools of liquid assets, and potentially earn negative returns on deposits.

August 5

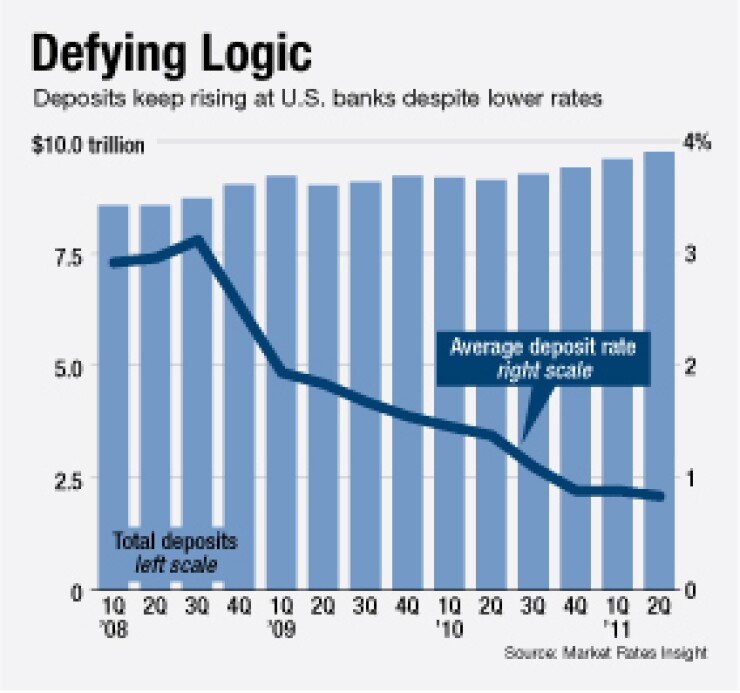

Cash on deposit has swelled to a record high at the worst imaginable time for banks.

Numerous institutions are trying to lower costs by cutting rates for certificates of deposit and money market accounts, but customers continue to park money in the bank as a safe haven from volatility. Reinvestment opportunities remain scarce for bankers, leaving many desperate and frustrated.

In fact some bankers are even questioning whether interest-bearing accounts are worth the cost of retaining the customers.

"My father yells at me all the time about the [low] rates we're paying at this point," says Robert DeAlmeida, the president of Hamilton Federal Bank in Baltimore. "We keep lowering rates but we have a tremendous amount of cash coming in for deposits, plus loan repayments. It's difficult to manage our spread."

Hamilton remains profitable but deposits are nearly 10% above what the $330 million-asset thrift had budgeting for this year. Likewise, total U.S. deposits were up 2% from a quarter earlier, to $9.8 trillion at June 30.

That mark is the highest on record with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Normally bankers covet liquidity from low-cost funding, but weak yields on investment securities and negligible loan growth are making most reconsider whether they really want the cash.

"Banks don't want a bunch of deposits. They want ways to grow their earning asset base," says Brett Rabatin, an analyst at Sterne, Agee & Leach Inc. "Deposit flows are so strong that if they pick up $1 billion in deposits, it places pressure on their capital ratios because the balance sheet balloons."

The number of unprofitable institutions fell slightly in the second quarter from a quarter earlier, to 1,145. But observers fear that those numbers could spike as balance sheets become severely unbalanced, wreaking havoc on the net interest margin.

A harrowing indicator is net interest income, which during the second quarter hit its lowest level since the fourth quarter of 2009, at $105.9 billion among more than 7,500 banks insured by the FDIC.

"Interest expense and interest income are on a course of collision," says Dan Geller, an executive vice president of Market Rates Insight. "At some point, something must give in order to preserve net interest income."

Geller and others say that more banks will be forced to follow the "cost reversal" strategy of Bank of New York Mellon Corp. The $304.7 billion-asset company said this month that it would charge a 0.13% interest rate fee to customers with more than $50 million on deposit in the bank.

"In my opinion, it will trickle down to retail banks but the largest retail banks will be first to follow," Geller says. "Relatively large deposits are cost prohibitive for banks to carry because of the soft lending market."

Still, observers say that community banks do not have fee structures in place like the larger banks, nor do they want to lose customers by charging outlandish fees.

This has left banks like Trustmark Corp. in Jackson, Miss., looking for ways to restructure its deposit products to generate fee income without imposing monthly charges. The $9.7 billion-asset company still offers free checking but with limits, including fees that kick in after a certain amount of debit card charges or calls made to the teller line or call center.

Barry Planch, a product management manager at Trustmark, says the new rules would go largely unnoticed by about 70% of the company's depositors. The remaining 30% are likely to close secondary accounts or switch to a bank that offers completely free checking, he says.

Rabatin pointed to a strategy by SVB Financial Group in Santa Clara, Calif., which has moved some depositors to off-balance sheet products to control costs and bolster its net interest margin.

A spokeswoman for the $19.4 billion-asset company declined to comment.

Most community banks are not as dynamic as SVB Financial, which focuses on technology, life sciences and venture capital. Some observers argue that smaller banks must get creative within the constraints of tightened regulation.

"This is opportunity for bankers to have the foresight to find industries, whether it's social media or some new biotech company that needs a champion in finance," says Richard Magrann-Wells, who leads the North American financial services practice at insurance broker and consulting firm Willis Group Holdings. "There are going to be clever bankers out there in knowing how to leverage that," Magrann-Wells added.

Geller argues that the decision by larger banks to charge for deposits will give community banks a competitive advantage. Though more customers means higher deposits, at least the bank has an opportunity to offer other products and balance the cost.

"The key to survival today is cross-sell," Geller says. "Community banks have a much greater opportunity for cross selling because they are much closer to their customer."