-

Families that own capital-starved banks are facing the decision whether to raise capital from outside investors — saving the banks but diluting their own stakes — or to keep pumping money into them to keep them alive.

November 10 -

Family wealth services are usually outsourced, but US Bank has brought on a PhD in psychology and a certified executive coach to work with their high-net-worth customers.

November 1

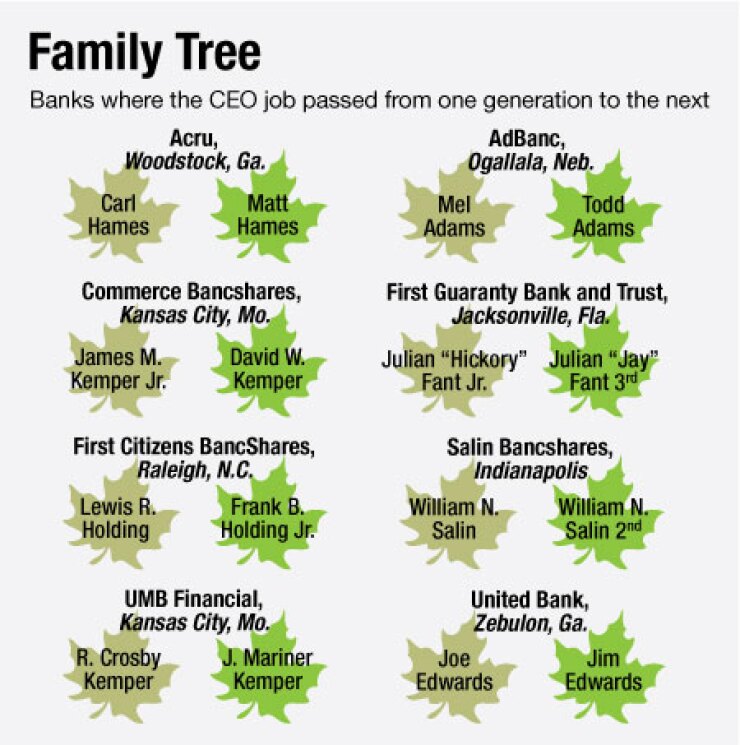

At banks where a child succeeds a parent as chief executive, moving from one generation to the next can be tough. Operating in the most difficult banking environment in recent memory makes the transition even trickier.

Consider the case of Community Bank of Loganville, a $681 million-asset bank in Georgia that regulators closed in November 2008. Members of the Kelley family, led by CEO Stan Kelley, worked at the bank, which had been run by family members for more than a century, said Walt Moeling, a banking lawyer at Bryan Cave LLP.

Then the residential real estate market around Atlanta collapsed, leading to a rash of bank failures. Moeling said the younger members of the family had previously convinced their elders to "go into riskier business lines" before the collapse, Moeling said. As a result, the once-conservative bank suffered the same fate as dozens of other banks in the state.

"It's a fact of life and a painful one when you see it happen," Moeling said.

Community Bankers Trust in Glen Allen, Va., picked up Community Bank in a deal with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Rex L. Smith 3rd, the buyer's CEO, could not be reached for comment.

Many more community banks face a plethora of difficult choices, such as whether to cut ties with a struggling bank or to invest more in the company in hopes of a turnaround. At family owned banks, the decision also includes an emotional attachment.

Another variable is thrown into the equation when a bank's longtime CEO nears retirement and one of his or her children appears to be the heir apparent. Family members who own stakes in the bank and the board must always make the institution their top priority, said David H. Baris, a partner BuckleySandler and the director of the American Association of Bank Directors.

"Having family involved in an institution can be a real plus," Baris said. "But if you get into a situation where certain family members are not qualified, then it can sometimes be a difficult process of separating the family and its support of the bank from what might be in the best interests of the bank."

At some banks where the child replaced the parent, the older generation never really leaves.

"We don't always agree with my dad and uncle and we have some lively discussions some time," the younger Edwards said. "But at end of the day, there is a huge amount of respect for the bank we all built. We take it very seriously and we don't want to mess it up."

Rather than succumbing to the financial crisis, United has ended up buying other failed banks in Georgia.

Boards should establish succession plans to protect the banks and themselves, even at the risk of hurting feelings or straining friendships, said Philip K. Smith, a banking lawyer and consultant at Gerrish McCreary Smith. Such a plan can lay the groundwork and timeline for a child to ease into the parent's role. If it turns out the child is not the right fit, the board has the ability to make a decision.

"You don't want to put all your eggs in one basket and it turn out to be wrong," Smith said.

A succession plan also puts into writing what a chief executive has in mind for how the next-generation leader will take over, Smith said. Many times that plan only exists in the CEO's mind and directors may not be privy to the details.

If a family wants to keep a bank in family hands, a succession plan serves as an insurance policy against an outsider coming in to take over the bank, Smith said.

"Often stockholders have relied so heavily on one individual, when that person retires, the board becomes nervous about finding an outside person," Smith said. "They're not certain if the next generation can handle it. The board decides they don't want an unknown leading the bank, so they decide to sell it."

The issue cuts both ways. Directors can also face a decision of replacing a parent with a child who might seem more qualified for the top post, Baris said.

"We've seen it both ways," Baris said. "Grandchildren or children can sometimes be more qualified than the older generation."

Family members have also been known to temporarily step into the CEO role. Sidney Brown, the son of Bernard Brown, chairman of Sun Bancorp in Vineland, N.J., served several months as interim CEO after the company fired Thomas Bracken in January 2007. The younger Brown returned to his post as a Sun director after the $3.5 billion-asset company hired Thomas X. Geisel as its permanent CEO.

The jury is out on some parent-child transitions.

After Matt Hames succeeded his father, Carl, as CEO of First Cherokee State Bank in Woodstock, Ga., the bank made several big changes. The younger Hames changed the name of the holding company to Acru Inc., named for the company's wealth-management unit. Then he hired an architectural firm and restaurant consultants to design and build a cutting-edge coffee house located in the upscale downtown area of Woodstock, just north of Atlanta.

The younger Hames' vision is to retire the well-worn model of a bank located in stuffy, columned brick buildings, replacing them with informal, modern-designed areas where customers can discuss finances with experts over a latte.

The first coffee house opened this summer. It wasn't difficult talking his father, or the bank's directors, into the risky move, the younger Hames said, since the bank had been battered by the decline of real estate values in metro Atlanta.

"We've identifed what we believe the next generation of community banking needs to look like," Matt Hames said.