-

A proposal to allow more small banks to avoid SEC registration will be highlighted by the Senate Banking Committee on Thursday — a sign that the issue has become a priority on Capitol Hill.

November 30 -

Banks are moving closer to getting the threshold raised for SEC stock registration.

July 21

A flurry of small publicly traded banks is expected to deregister from the Securities and Exchange Commission next year as bankers search for relief from regulatory expenses.

Currently, companies with 500 shareholders or more must register with the SEC and can deregister at 300 shareholders or fewer. A bill in the Senate would allow banks with fewer than 2,000 shareholders to avoid SEC registration; banks dropping below 1,200 could deregister.

If passed, the legislation could release many smaller banks from the SEC's watchful eye, potentially saving up to $1 million in annual regulatory compliance costs, observers say.

"We're all trying to find ways to just do business while trying to comply with regulation so we need to get as much unnecessary expense out of the organization as possible," said Menzo Case, the chairman, president and chief executive of Seneca-Cayuga Bancorp Inc. in Seneca Falls, N.Y. "We can't have a bag of regulation tied around our throat that just drags us down for reporting."

The company deregistered on Sept. 11, 2009, with 277 shareholders at the time. Since then, Case says the company is saving more than $200,000 annually in regulatory costs. "With the Dodd-Frank [Act] and the conservative effort to drive banks out of business, [the savings] make a big difference," he says.

Seneca-Cayuga Bancorp went public in 2006 with fewer than 300 shareholders but voluntarily registered with the SEC because Case wanted to attract investors. He says that, over time, the required filings with the SEC were "of no value" and certain internal auditing costs tied to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act led it to deregister. "We've already got internal auditors, external auditors and the regulators are all over us," Case says. "The last thing that we need is an internal control audit."

Since deregistering, the company's bank, Seneca Falls Savings Bank improved its efficiency ratio to 74.6% at Sept. 30, compared with 87.4% at June 30, 2009, before its deregistration.

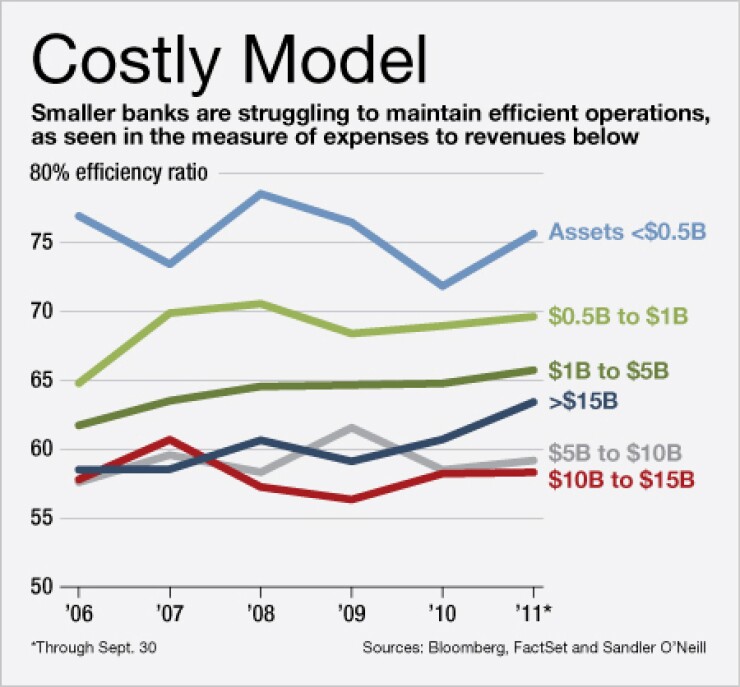

Banks with fewer than $1 billion of assets often have higher efficiency ratios than larger banks. The ratio at banks with fewer than $500 million of assets has jumped significantly this year, to 75.6% at Sept. 30, compared with 71.8% at the end of 2010, based on data compiled by Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP.

With regulatory costs expected to keep rising, observers say more smaller banks will deregister, especially if legislation is passed to raise the 300 shareholder deregistration threshold. "I've gotten more calls from bankers on this issue than any other single issue," says Cecelia Calaby, a senior vice president of the American Bankers Association's Center for Securities, Trusts and Investments.

The ABA and the Independent Community Bankers of America are supporting the bill co-sponsored by Republican Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison and Democratic Sen. Mark Pryor.

While it is difficult to get aggregate data on deregistered banks or total shareholder counts, the ABA estimates nearly 200 banks have 500 to 1,200 shareholders. Supporters say the bill could benefit some of the roughly 6,600 private banks that are constrained from raising capital for fear of exceeding the existing 500 threshold.

"Community banks are a little unique. They have to raise and hold more capital, so they tend to have more shareholders than a typical small business," says Paul Merski, the ICBA's chief economist. Because of this, "they tend to get tripped up by the 500-shareholder requirement."

While proponents see the proposal as a way to help banks raise capital and cut costs, a downside is that investors could be denied certain data required by the SEC. "The SEC has extensive regulations and requirements governing disclosure regarding executive compensation and a company's financial condition and results of operations, among other things," says Matt Kaplan, a corporate partner at Debevoise & Plimpton LLP specializing in capital markets.

Also the SEC requires "real-time" reporting of certain material events such as debt issuances and the entry into a bank merger or acquisition. After a deregistration, "any investor who is thoughtful about their investments probably would notice the reduction in the extent of company disclosure provided," he says.

Executives at smaller banks say they are already thinly traded, so investors would not be materially disrupted if the bank deregistered. Banking regulators already require banks to publicly disclose their financials. "We've provided enough analysis to let [investors] know what's going on and they can always contact us," Case says. He adds that deregistration would not stop a bank from raising capital as long as it has a good story.