-

No, the merger wave isn't here, but it has to start somewhere. Data through May 31 shows a foundation to build on once uncertainties about U.S. elections and European economy ease.

June 8 -

Investors are now willing to put money into community lenders with credible business plans, sufficient scale, and executives who show "courage" and "fortitude," says Greg Mitchell, CEO of First PacTrust.

May 22 -

Daryl Byrd, the CEO of Iberiabank (IBKC) says a wave of bank mergers is inevitable and will be larger than expected. Rusty Cloutier, his counterpart at MidSouth Bancorp (MSL), says a lack of able buyers is miring consolidation.

May 21

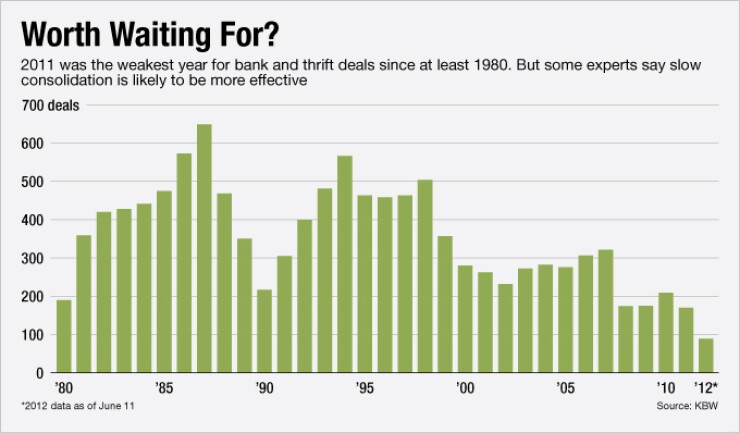

Contrary to popular belief, consolidation may be better for banking as a stream than a wave.

Dealmakers have set high expectations for mergers and acquisitions in the post-crisis era, based on arguably unrealistic assumptions from bygone times. As a result, the smallest of deals draw scrutiny and momentarily fuel the seekers of M&A momentum. Insiders rue a quiet week and lament the overall slow pace of deals as bad.

Yet rapid consolidation is neither a mandate nor universally embraced. The current pace of mergers and acquisitions is just fine for healthy banks and consumers, even if it is slow for the architects of the deals, many experts say.

"The banking system may be healthier with fewer participants, but that's not tangible to the consumer. The greatest disappointment [with the slow pace] may be among M&A advisors, those who profit from it," says

There are many good reasons for companies to partner up. Buyers could gain economies of scale that reward their shareholders, and some sellers can provide their shareholders an exit at a premium or a brighter future with a stronger company.

Still, not everyone benefits from bank M&A. Communities are left with fewer options, and

"M&A is a neutral term," said Cornelius Hurley, director of the Morin Center for Banking and Financial Law at Boston University. "We tend to have this monomaniacal focus on shareholder value …but that is only because we do not factor in things like the closeness of the community, jobs and the things like the consequences of too big to fail. There are a lot of intangibles that Milton Friedman never thought about."

(Friedman, the celebrated economist who died in 2006, preached that increasing profits through legitimate methods was the only social responsibility businesses have. )

The participants do not always benefit from mergers either. The M&A frenzy in the years preceding the 2008 meltdown may be the best argument for taking things slowly. Consolidation may prove to be a good thing, but the pressure to do it quickly can prompt bad decisions.

A Moody's Investors Service report this month favorably noted that mergers and acquisitions — including failed-bank deals — are on pace to fall 46% this year compared with the average from 2002 through 2011. The credit rating agency viewed the slowdown as a positive because it likely indicates banks are taking a more measured approach.

"A slowdown in consolidation is not necessarily a negative. In fact, it is a positive if it reflects an underlying discipline," Allen Tischler, a senior vice president at Moody's and the author of the report, said in an interview. "From our perspective, it is not a case of good year or bad year; we are more focused on what an acquisition will do to an acquirer's credit profile."

The report pointed to the damage caused

It also cited several ill-timed ventures into Florida by out-of-state buyers. Park National's (PRK) 2007 acquisition of Vision Bank in Panama City, Fla., is one such example. The Newark, Ohio, company entered the Sunshine State anticipating a robust market. Instead, it got a bank burdened with nonperforming assets that cut into earnings for years.

"History shows that in their zeal to expand, banks often undertake poorly timed or ill-advised acquisitions, and they frequently take on too much leverage in the process," Tischler wrote in the report.

There are places where the industry can tighten up. The so-called zombie banks that are still dealing with a high level of nonperforming assets are one example.

"We have these banks that are referred to as bucket shops," Hurley said. "They are poorly managed and truly deserve to be put out of their misery."

The Dodd-Frank Act, coupled with the inability to find scale or growth, will push some banks out of the picture, says Chip MacDonald, a partner at Jones Day. In those cases, acquisitions could be safer than the excessive risks those banks might take.

"We need to have stronger institutions that will be able to absorb the costs brought up by new regulations and the artificially low interest rate environment resulting from [Federal Reserve] monetary policies," MacDonald says. "The alternative is that those policies might push people to take more risk to reach for yield."

J. Grant Smith, the chief executive of the $114 million-asset Clarkston Financial in Michigan, rejects the notion that a small community bank cannot make it on its own.

"I'm not a proponent of consolidation. I think the investment banking community drives that chatter. I think there is a point where scale matters, but that is driven on where you are," says Smith, who formerly worked for the Office of Thrift Supervision.

Hickey agreed. Though his firm has been successful in helping banks find buyers or capital, some banks might be just fine going at it alone, he says.

"It might be difficult to provide an acceptable return if you are below a specific size, but for a family owned bank in the Midwest that does great things for the community it serves, I don't know how important maximizing returns are to them," Hickey says. "It is not always about the bottom line."