A new round of tariffs imposed Thursday has raised alarm among economists, lawmakers and financial analysts not just for their impact on trade flows and prices, but for the ripple effects on the financial sector.

Broad tariffs on more than 90 countries went into effect Thursday, following the president's previously announced deadline for countries to negotiate a trade deal with the U.S. The move brings the average tariff rate to 18%, compared with just over 2% when Trump took office in January.

The highest rates were imposed on countries heavily involved in manufacturing, including Myanmar and Laos, which face a 40% levy on imports to the United States. Switzerland will face a 39% rate, Canada will face a 35% tariff and Mexico will face 25%.

While the administration says the duties could generate up to $50 billion per month, critics say the measures will more likely increase costs for consumers and complicate financial planning for firms and lenders alike.

"Tariffs are flowing into the USA at levels not thought even possible!"

Thursday's tariffs triggered modest declines in U.S. stock indexes, with the Dow and S&P 500 slipping while the Nasdaq held steady near record highs. Economist Ina Simonovska, associate professor at the University of California, Davis, says that market reaction suggests that investors may not have really believed that the president would impose tariffs as high and sweeping as he has.

"I was frankly surprised that markets went down, because I thought that this was already priced in … this has been announced for a while, so it was to be expected," Simonovska said. "But I suppose that just sort of tells you that uncertainty really has been in the background, that perhaps markets didn't believe that these tariffs would kick in, and now they did."

Simonovska points out that while the overall situation is expected, some aspects were not. The threat of 50% tariffs on India, which Trump has said is in response to India's purchases of Russian oil, is more concerning, she said, though she says this represents a strategic move aimed at weakening India's ties with Russia.

The threat toward certain countries, like India, reflects tension in negotiations, says Philip A. Luck, director of the CSIS Economics Program and a former deputy chief economist at the U.S. Department of State under the Biden administration.

"The negotiations didn't go well," Luck said. "The administration has been pushing them really hard on reducing barriers to U.S. agriculture … that is basically a non-starter for India, because just a huge amount of their population relies on agriculture production. And so [India] would be threatening the economic security of millions and millions of people if they gave in on that. So they're simply not going to do it."

Derek Tang, CEO of Monetary Policy Analytics, says the current trade escalation is increasingly a political cudgel. While tariffs were initially justified by the administration on the grounds that they would boost U.S. manufacturing and reduce trade deficits, Tang said, they seem designed to serve broader geopolitical and political goals.

"The grounds are more … about the White House's international geopolitical goals," Tang said. "Weeks ago, there were tariffs enacted against Brazil on the grounds that they had some domestic political issues that the White House disagreed with. Tariffs are now very clearly an all-purpose tool to … incentivize other countries to act in the U.S. national interest."

Luck says the current tariffs represent Trump making good on his promises to reshape the U.S. trading system, with higher tariffs across most partners a big change from the status quo in the previous administrations. But what is most surprising, Luck said, is that the tariffs largely hew to the vision Trump first laid out in April.

"Markets are behaving like none of this stuff went into place, even though it all did," he says. "Compare the response today to the response on Liberation Day — it's night and day. And the policy is almost identical."

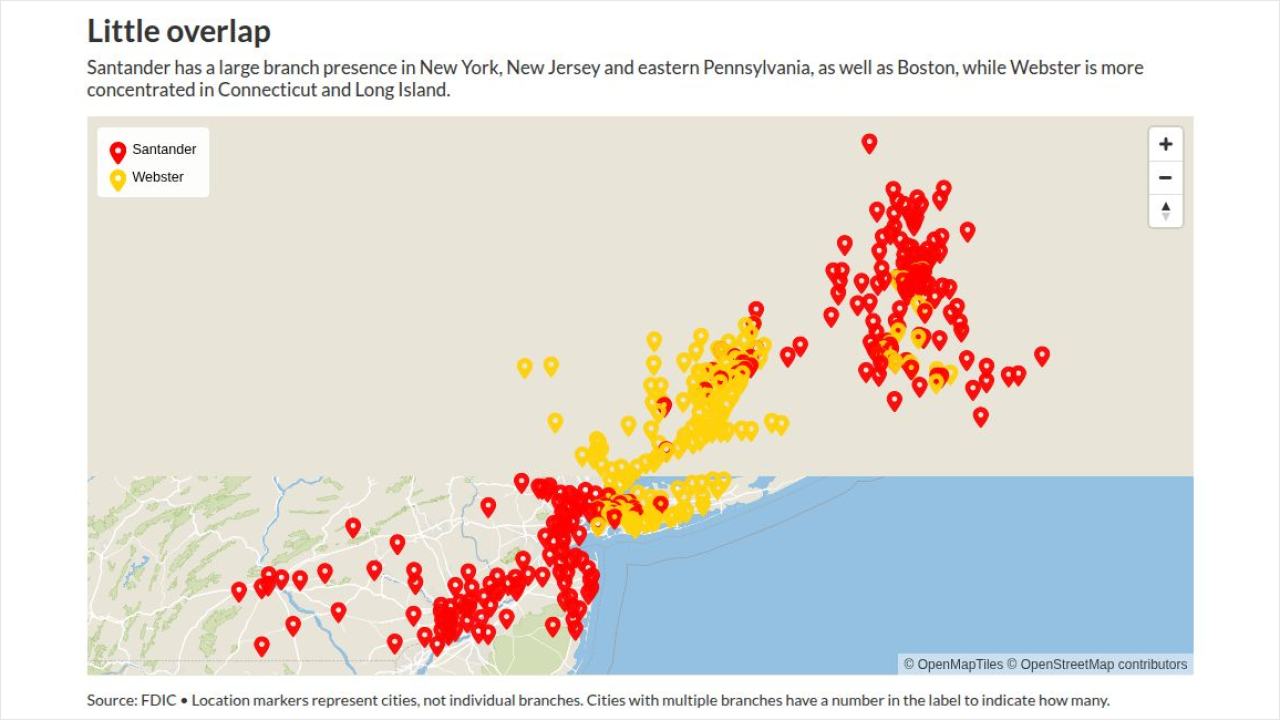

That shift has wide ripple effects — not just for manufacturers and consumers, but also for the financial institutions that support global trade. Banks support commercial clients dealing with trade uncertainty by facilitating international payments and capital flows. As companies move production from tariffed jurisdictions like China to other regions, Tang says banks provide essential services like local banking presence and help with capital controls.

"Banks play an important role in facilitating those flows," Tang said. "[Helping businesses transition] into other geographies requires a lot of pre-positioning in terms of not just the capital flows to make upfront investment as well as a local banking presence. Banks with strong international franchises stand to do quite well."

Tariffs can cause financial firms to scale back certain activities. A 2023 paper by researchers at the New York Federal Reserve

"In the meantime, you just have to accept that you have a high level of risk [in places facing tariffs] so if you're targeting an average level of risk, what this means is that you have to make up for it elsewhere," Tang said. "That might actually mean pulling back on lending, maybe even domestically in the U.S., so that overall your risk exposure is not too high."

Luck calls the tariffs a large, distortionary tax that will disproportionately hurt low-income households by raising consumer prices and production costs. He says that while the tariffs will slow growth and raise costs, the U.S. economy's strengths mean it won't crash, it will just perform worse than it could without the tariffs.

"Prices of goods are going to go up and our competitiveness in export markets is going to go down," he said. "You should think about this as a drag on the tailwind the U.S. economy has, [but] it's not going to crater the economy."

Luck expresses surprise that markets haven't reacted more sharply. He suggests that investors may be misreading the administration's tone when it comes to scaling back tariffs.

Simonovska says while tariffs are likely to push prices up and increase pressure on the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates, the situation is more nuanced. She says internal disagreement among Fed officials about the relative economic downsides of higher unemployment or higher inflation and an uncertain inflationary effect of tariffs make the Fed's interest rate path less clear.

"It's not at all obvious that the Fed really needs to address the effect of tariffs," Simonovska said. "At the end of the day, there's just so much uncertainty, and that's really what everybody's reacting to. I can see banks reacting to uncertainty, even though, rationally, given what we've seen with the behavior of the Fed, there's really no reason for concern."