PNC Financial Services Group is far from the flashiest bank around. The Pittsburgh-based bank isn't a megabank like JPMorgan Chase or Bank of America, nor is it engaged in the massive deals that those two arrange on Wall Street. It's no laggard in technology, but it's not the first bank that comes to mind in that regard either.

In fact, one could even say PNC is boring. But in a

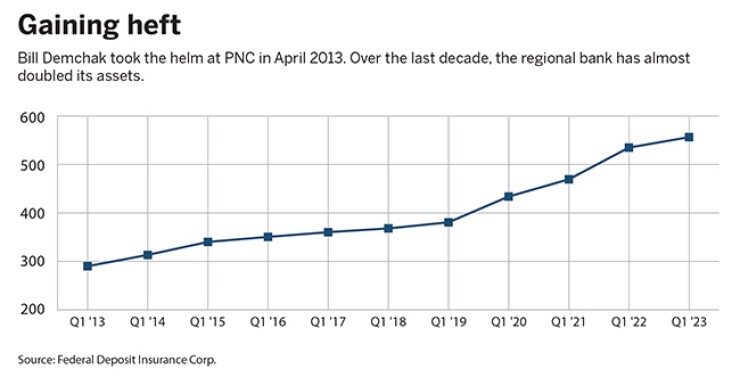

PNC, which at $557 billion in assets is the eighth largest U.S. bank, calls itself a national Main Street bank. It focuses on middle-market businesses, ones that aren't household names but still play a critical role in the U.S. economy. Its roots are in Pittsburgh, but it's steadily expanded and now has a national, coast-to-coast footprint.

Leading the charge is Bill Demchak, who's been PNC's CEO since 2013 and has spent two decades at the bank.

Demchak, whom American Banker is naming Banker of the Year for 2023, declined an interview request. But analysts credit his steady hand for growing PNC into a strong national franchise — one that isn't immune to industrywide pressures but often finds a way to the top of the pack.

"The investment community is willing to bet on Bill Demchak and bet on PNC, because of the track record that he and the company has had throughout multiple cycles," said Terry McEvoy, an analyst at Stephens. "That reflects a high level of credibility. That doesn't happen overnight within the banking sector."

Few investors are buying bank stocks this year, but those who are often think PNC would be more resilient if a recession hits.

"Investors are looking for high-quality, defensive names … sleep-at-night stocks," said Ebrahim Poonawala, an analyst at Bank of America. "PNC is one of those that comes up often."

This year, as worries over regional banks popped up, PNC found itself in a stronger position than some competitors.

Dozens of banks reported deposit outflows after Silicon Valley Bank's failure in March, but PNC

To be sure, PNC isn't impervious to the struggles facing the banking industry. Its profitability is down as depositors seek higher interest rates, prompting PNC to

But other regional banks are facing bigger earnings pressures, or they're needing to readjust more as regulations get tougher. PNC, in contrast, more skillfully prepared its balance sheet for whatever comes next, making sure it had more capital and thus flexibility.

"They continue to grind away one step at a time, with calculated risks, to show consistent progress," said Wells Fargo analyst Mike Mayo.

He added that Demchak has proven to be one of the "most independent-thinking bank CEOs."

The tougher environment has many regional banks

Its balance sheet gave it ample room to

If the price is right, PNC may also gain valuable customers from competitors whose slimming-down campaigns are prompting them to exit some businesses. Doing so may be "pretty attractive" for PNC, Demchak told analysts Oct. 13 when asked about the possibility.

"We're intelligent — hopefully, intelligent — takers of risk at the right price," Demchak said. "We can evaluate what's out there."

Becoming a national Main Street bank

Demchak came to PNC in 2002 as chief financial officer, marking his return to his hometown of Pittsburgh after a high-profile stint on Wall Street. Demchak helped lead JPMorgan's development of credit derivatives products, the type of financial engineering that contributed to the 2008 financial crash.

The Financial Times

The idea behind those derivatives was simple. Corporations and investors could already swap the risks tied to interest rates, currencies and commodity prices. If a company feared interest rates or the price of oil would rise, they could protect themselves by swapping that risk with another entity, which took the other side of that bet.

In the mid-1990s, Demchak and the JPMorgan team were on the forefront of applying that same idea to the chance that companies may default on their loans. If used correctly, the innovation could help spread the risk of a loan turning bad — with banks swapping the risk of borrowers defaulting on their loans to investors willing to take bets on those outcomes.

The usage of credit default swaps proliferated. Demchak and the JPMorgan team had focused on using them in the corporate world, where ample data on companies' financial health made it easier to run statistical analyses.

But other banks and Wall Street firms soon created credit default swaps based on consumer mortgages — where historical data was more sparse and lenders were becoming far too lax. The JPMorgan team had long viewed mortgage derivatives with caution, which insulated the bank when the subprime mortgage crisis hit.

Demchak stuck to that more cautious view when he joined PNC in 2002. The bank took a more conservative approach in the years leading up to the 2008 crisis and limited its exposure to dicier sectors.

At a November 2007 presentation, Demchak noted the bank stayed away from subprime mortgages, had fewer real estate loans than its peers and was cautious on corporate credit conditions. The bank had been selling loans where it could and keeping its balance sheet slim, which reduced its profits but put it in better shape for a downturn that was already starting to brew.

"We didn't grow the balance sheet as quickly as we could because we were worried about the risk embedded in that, and it is pretty clear today that our position has been validated by the headlines and the real world outcomes," Demchak said at the 2007 event, according to a FactSet transcript.

PNC's healthier financial footing helped it acquire National City Corp. when the Cleveland-based bank ran into trouble in 2008. The crisis-era purchase gave PNC a strong presence in the Midwest and turned it into the country's fifth biggest bank by deposits.

Then-CEO James Rohr, along with

The deal-making slowed once Demchak became CEO in 2013. But he

The BBVA USA deal finally accomplished PNC's mission: taking the bank national. PNC branches now stretch from coast to coast, and the bank is in all 30 of the largest U.S. markets.

However, that deal followed a questionable move from PNC. In May 2020, as COVID-19 uncertainty continued to cloud the economy, PNC

Had it waited a few more months, PNC would have reaped far more cash, and not prompted Barron's to criticize the "folly" in the sale.

On the plus side, PNC was able to use the proceeds to buy BBVA's U.S. operations a few months later. And since few banks were interested in acquisitions in 2020, PNC was able to get BBVA for fairly cheap, said Poonawala, the Bank of America analyst.

So far, the BBVA deal seems to be going well. Mayo, the Wells Fargo analyst, praised PNC for being able to integrate the two systems together quickly for customers.

Other banks, such as PNC's North Carolina-based rival Truist Financial, have

But the smooth integration of BBVA is partly thanks to PNC's long efforts to improve its data infrastructure and make the company more efficient, Mayo said. Those efforts may not be all that exciting, but the integration showed how "10-plus years of back-office restructuring and tinkering pays off," he said. It's yet another reason why Mayo calls PNC the "bank of steel," a nod to its Pittsburgh roots but also the resiliency of its technology and balance sheet.

"It got a bit rusty with the sale of BlackRock for a period, but then it took some of that rust off," Mayo said, noting PNC "made victory out of defeat" by using the BlackRock sale proceeds to buy BBVA at a great price.

Blythe Masters, who worked for Demchak at JPMorgan and rose to other top roles at the megabank, said he is "one of, if not the, most talented individuals I have worked with or for.

"He is an exceptional judge of talent, an intuitive and detail-oriented risk manager, a deeply strategic thinker and capable of playing a long game," said Masters, who's now founding partner of the tech investment firm Motive Partners.

"I'm delighted, but not remotely surprised, that he and his team have made PNC such a great success," Masters added.

Preparing for a rainy day

How PNC fares in a downturn — assuming the U.S. economy will eventually break its streak of outperforming expectations — remains to be seen.

Like any other bank, it would lose money as consumers fall behind on their payments and businesses struggle to pay back loans. But analysts point to PNC's solid history of outperforming other banks on credit quality as a sign that its underwriting is solid.

And in the sector that's currently the biggest source of worry — empty office buildings as some employers offer remote and hybrid work options — PNC's exposure is relatively low.

Some 2.8% of PNC's loans were in office-related commercial real estate as of last year, according to a Jefferies analysis of large and regional banks' office CRE exposures.

While that was above the median of 1.7%, some competitors such as Citizens Financial Group, M&T Bank and Wells Fargo have about 4% of their total loans in office CRE. Several midsize banks that are significantly smaller than PNC have much larger exposures.

Whether office leases will be a major source of trouble in the coming months is unclear. Some argue the pain will be gradual, since office leases often stretch several years and the tenants won't leave all at once. Others worry vacancy trends, high interest rates and other factors will lead to more stress — particularly at midsize banks that are more exposed.

PNC has been monitoring the situation closely and stashing away reserves to cover the potential souring of office loans.

"We'll need those reserves because we do think there's going to be problems in the office space," Demchak told analysts in July.

For borrowers who do run into problems, PNC is working to figure out other options, such as selling buildings if needed or getting more equity from their investors.

The bank is also giving its own investors a detailed overview of its office loans — whether they're in downtowns or suburban areas; whether they're medical offices and thus less exposed to work-from-home trends; and whether any have seen stress thus far.

In some ways, Stephens' McEvoy said, PNC's moderate exposures to the office sector lines up with its history. It was less exposed to housing in 2008, but also to the energy sector when a slump there prompted charge-offs at banks around 2015.

"It just seems like PNC always ends up having less exposure to whatever problem lending category is out there," McEvoy said.

The bank is "not immune to the operating environment," Poonawala said. But, he added, Demchak's leadership has instilled confidence that "PNC should be able to navigate whatever the cycle looks like."