Obscure clauses in securitization documents could spell big losses for banks if Congress passes mortgage bankruptcy legislation.

U.S. banks and thrifts hold hundreds of billions of dollars of nonagency mortgage-backed securities. Most if not all of these bonds are rated triple-A, meaning that normally they would be well cushioned against any loss, as lower-rated classes would take a hit first.

However, many securitization documents contain language that identifies bankruptcy as a condition in which all bondholders share losses equally. Such clauses have been common since at least the 1990s but made little difference in the real world because the U.S. Bankruptcy Code does not let judges rewrite mortgages on primary residences. A bill approved by the House Judiciary Committee last month would give judges that right.

"If the legislation is passed, I fail to see how banks would not be sellers of this paper," said William Frey, the president of Greenwich Financial Services LLC, a hedge fund in Connecticut. "You'll see a portion of MBS paper dumped into a very illiquid market" — meaning the securities would fetch low prices.

But analysts said that, if banks hold on to the bonds, they would still feel repercussions — even before their cash flows were affected by any judge's decision.

This is because the legislation's enactment might prompt the ratings agencies to downgrade the triple-A bonds. Observers said such downgradings would have two consequences for banks: They would have to set aside additional capital, since the bonds would now have a higher regulatory risk-weighting than before, and they would have to write down the assets to reflect their lower market value.

"If a bond goes from triple-A to triple-B, that's a permanent impairment, and a high percentage of these bonds would no longer be investment-grade, which means they're not even legal to hold for these institutions," said Robert Pardes, a managing director at RRMS Advisors LLC in New York. "Now you have a whole new, unpredictable variable, and nobody has agreed on how to account for it."

Mr. Pardes said he recently analyzed a large portfolio of triple-A bonds for a bank and found roughly 5% would have an impairment of some kind if the bankruptcy bill passes.

Since a large chunk of such mortgage securities are in the held-for-investment portfolios of large banks, he said, even "the most conservative banks may realize 'other-than-temporary' impairments" and may have to mark the securities down or move them to held-for-sale portfolios.

John Sim, an analyst of mortgage-backed securities at JPMorgan Chase & Co., wrote in a report published last month that roughly 40% of prime and alternative-A mortgage securitizations contain language in which "losses as a result of bankruptcies can hit every bond in the capital structure."

A 2006 pooling and servicing agreement from JPMorgan Chase states: "With respect to each mortgage loan in the related mortgage pool that became subject to a bankruptcy loss … , such excess losses shall be allocated among all classes."

Sajjad Naqvi, the chief credit officer at TCW Group Inc., a Los Angeles investment management firm, said it is early to form conclusions about the impact on banks because the bankruptcy legislation has not been completed and the securitization deals' language varies dramatically.

"We're all trying to assess an impact of legislation that has not yet been written," he said. "But if there are downgrades to those securities, then the securities would be worth less and banks' balance sheets would contract."

Mr. Sim wrote that, if the legislation is enacted, "more bank writedowns would clearly result."

"Assets will need to be marked to market, with losses hitting income," he wrote. "Banks and insurance companies could be required to hold 10 times more capital."

Analysts are still trying to determine how many borrowers could potentially file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy protection, which would require them to stay on a stringent three- to five-year repayment plan.

Of the roughly 54 million outstanding mortgage loans, 2.5 million to 6.5 million could end up in bankruptcy, Mr. Sim estimated.

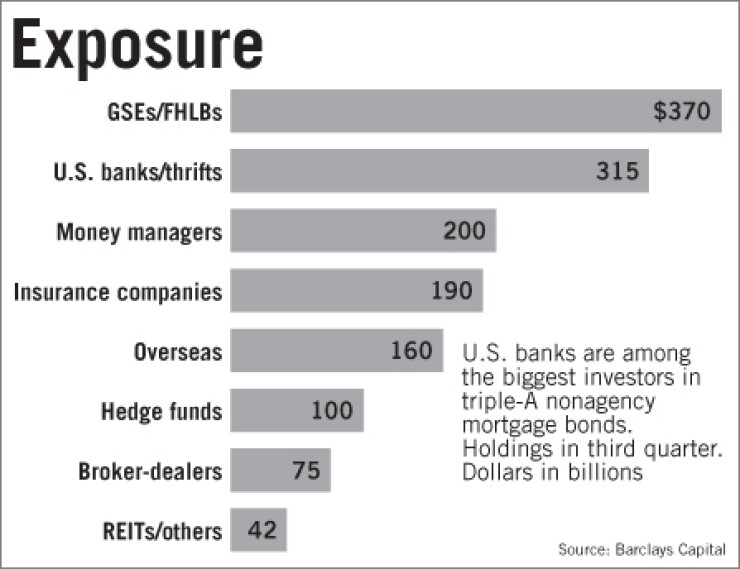

Banks held about $315 billion of nonagency mortgage-backed securities at Sept. 30, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Analysts at Barclays PLC's investment bank have estimated the overall size of this market at $1.45 trillion. They ranked U.S. banks and thrifts as the second-largest group of holders of nonagency mortgage securities, behind the government-sponsored enterprises and Federal Home Loan banks, which together had $370 billion.

Issuance of these securities — which do not carry guarantees from the GSEs or the government — has been moribund since the crisis began in July 2007. Some observers said the cramdown legislation could forestall a comeback.

"It doesn't just make things worse now, it makes things worse forever because the price of doing a securitization of mortgage-backed securities will go up because investors now have to cover some multiple of historic bankruptcies," said Jason Kravitt, a longtime securitization lawyer and a partner at Mayer Brown LLP.

Mr. Naqvi agreed.

"This is another issue that could cripple the industry because: How do you do a securitization if you know the rules can be changed?" he said.