Deposit prices on average dropped noticeably last month, in all likelihood a direct response to higher deposit insurance assessments.

Whatever the reason, the move appears counterintuitive, given how important deposits — and lots of them — will be to banks in the post-crisis era. For now, banks can keep deposit prices low, because competition for deposits from other investment classes is tepid as risk-averse consumers flock to the safest places for their money.

Just how much longer banks can lower their deposit rates without customers returning to the stock market and other potentially higher-yielding investments is unclear. The next test could come soon, as the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. is almost certain to charge a second special deposit insurance premium to account for increased bank failures.

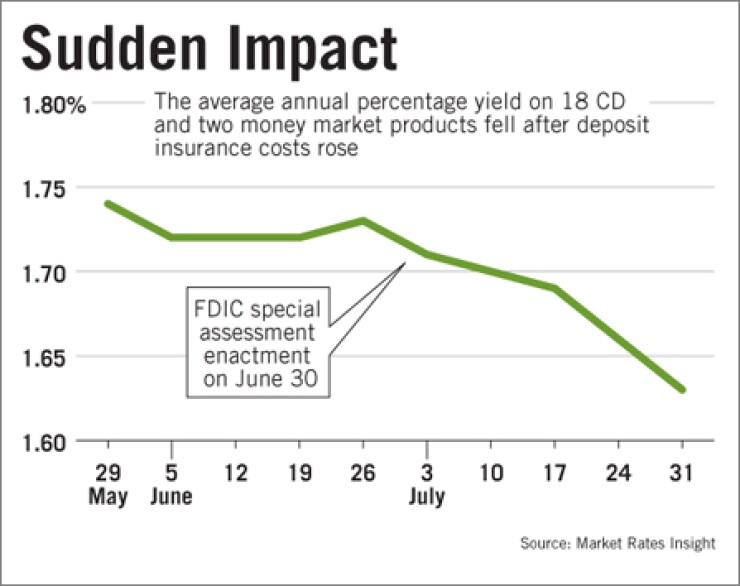

The average rate for 20 key deposit products dropped 10 basis points in July, according to Market Rates Insight, a San Anselmo, Calif., firm that tracks deposit pricing. The average rate remained unchanged for the month of June, and the firm strongly correlates the drop last month to banks lowering their deposit prices after the FDIC special assessment took effect June 30.

"The reason we saw such a relatively dramatic drop in the national [annual percentage yield] after that date is because banks waited until the last day before they had to start allocating their funds" to pay for the assessment, said Dan Geller, Market Rate Insight's executive vice president. "The money they saved by not paying out as much in deposits is paying for the special assessment."

The FDIC charged banks 5 cents for every $100 of assets minus Tier 1 capital. Moreover, the maximum assessment was 10 cents per $100 of domestic deposits, which corresponded closely with the cumulative drop in the national average rate since June 30, Geller said.

The firm calculated its cumulative national APY using 18 certificates of deposit products and two money market products.

No banks contacted for this article were willing to comment, except Citigroup Inc., whose spokesman Rob Julavits said the company has not passed along the FDIC assessment to customers in the form of lowered deposit rates.

But observers agreed that the industry has few choices to pay for the historically outsized special assessment.

"Banks are going to have to pass along the assessment one way or another — they're in the business of making money for their shareholders, and so they're either going to have to charge more on loans or less for deposits," said Sanford "Sandy" Brown, the Dallas office managing partner of Bracewell & Giuliani LLP.

Right now banks can more easily pass along the cost of the FDIC special assessment to customers, because deposit prices overall are low, said Kevin Fitzsimmons, an analyst for Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP.

"Many banks are able to push the assessment through, because deposit-pricing competition has gotten less and because the inflows into core deposits has given banks the ability to toggle down deposit rates," Fitzsimmons said.

Their customers have been willing to accept lower rates on certificates of deposit and money market accounts, which has enabled banks to shave a few more basis points from the offerings to pay for the FDIC assessment, he said.

However, in time customers may not be so willing to accept very low deposit rates, said Ron Glancz, a partner at Venable LLP.

Glancz said that observers are concerned about how the industry could be affected if banks have to continue absorbing increased regulatory and capital-raising costs — especially now that the FDIC is thinking of charging that second special assessment to keep the Deposit Insurance Fund afloat.

If banks were to lower deposit rates even more to cover the additional costs of a second assessment, customers may balk and go elsewhere, Glancz said.

"People who are getting a half-percent interest — and that's before taxes — may feel that they have to take a little more risk and look for alternative investments, such as stocks and bonds," he said.

In the three months since the FDIC adopted the first special assessment, 43 banks, with $41 billion of assets collectively, have collapsed, costing the insurance fund an estimated $8 billion. The collapses have taken a toll on federal reserves, which stood at $13 billion on March 31, their lowest point since 1993.

How much the FDIC would charge is debatable. A clearer picture will come Aug. 27, when the FDIC is scheduled to give its second-quarter report on the banking industry's health.