Growing weakness in commercial real estate is poised to transform banking companies into accidental landlords — with a new set of headaches.

Lenders have already endured trials from seizures of vast numbers of single-family homes. Properties that produce income and accommodate tenants — office buildings, apartment complexes, shopping malls and the like — carry a distinct set of problems, from "slip-and-fall" lawsuits to new varieties of public relations dust-ups.

Tenants have always had a fraught relationship with landlords. Following the blow to bankers' reputations from the financial crisis, the dual role could make for a particularly combustible mix.

"You can imagine some of the places where you might get the most public reaction. Suppose that you had municipal buildings that had been mortgaged to a bank. Suppose you had a nursing home," said Ralph "Chip" MacDonald, a partner with Jones Day. "The more complex the business" — hospitals are another example — "the less anxious the banks are going to be to get involved."

By and large, strapped home-owners are likelier candidates for public sympathy than property moguls on the brink. But indignation over bailouts has intersected with commercial lending relationships to produce unwanted attention for institutions like Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co. Their roles as creditors for the failing Illinois manufacturers Hartmarx Corp. and Republic Windows and Doors drew national headlines and political pressure for concessions.

"It has sort of become a rallying cry that somebody who receives" assistance from the Troubled Asset Relief Program "has different obligations than what they legally have," MacDonald said. "Tarp has become a burden-sharing exercise as opposed to temporary assistance to stabilize the system."

Reasons to Sell

To be sure, the complexities of real estate ownership are vastly overshadowed by prospective losses on a widely anticipated crescendo of bad debt. If a lender is packed with souring loans that put it in a position to become a big landlord, there is a good chance it is insolvent anyway.

Lenders can avoid coming into possession of properties by selling loans headed for trouble.

"There are some banks who would just rather sell their loans and get the loans off the books and not have to deal with it," said Jeffrey Lenobel, a partner with Schulte Roth & Zabel LLP.

"Lenders are generally not in the foreclosure mode because it's time-consuming, it's expensive, and then they obtain the property, and have to manage it, run it, lease it, sell it," he said. "They have to hire a managing agent. They have to deal with the economics of the property. If it's an office building, they have to lease it. … If it's a hotel, you have to enter into a franchise or operating arrangement."

MacDonald said that when banks do foreclose, they often put the collateral "in special-purpose, bankruptcy remote entities so that they don't get exposed to the liabilities of operating the commercial property, where you have potential tenant and visitor risk."

For example, at an industrial plant, "you worry about environmental liability," he said.

Regions Financial Corp. focuses on "getting loans moved before they go to foreclosure," said Tim Deighton, a spokesman for the Birmingham, Ala., banking company.

In late 2007, the $142 billion-asset Regions set up a division to unload distressed assets. Evelyn Mitchell, a spokeswoman, said one reason for the approach is the difficulty of going through the legal process for foreclosure.

In an interview last week, Synovus Financial Corp. Chief Executive Richard Anthony said his company was stepping up efforts to unload problem holdings to improve its credit profile. The $34.5 billion-asset Columbus, Ga., company has posted three consecutive quarterly losses as it increased its allowance for loan losses by 86 basis points from the year prior, to 2.32% of net loans at March 31.

Reasons to Hold

However, some market participants said banking companies are reluctant to sell distressed assets in general, including commercial real estate loans, because taking hits at current market values would ruin them.

The desire to hold assets until the market rebounds likewise provides an economic incentive to retain foreclosed real estate, plus the market for some properties is close to nonexistent.

David Gibbons, former deputy comptroller and chief credit officer at the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, now a special adviser to Promontory Financial Group LLC, said that though holding onto foreclosed property risks price drops, "depending on your timing, you could be dumping your property at very low prices." That happened in "the early '90s when banks acquired a lot of 'other real estate owned' and sold it and eliminated problems from their balance sheets," but "then somebody else made money because the market stabilized and got better."

Eric Michael Anton, an executive managing director with Eastern Consolidated, a New York commercial real estate sales firm, said that over the last six months, he has observed a pattern where banks "go to market, and they'll get the offers, and then they'll say, 'You know what? We're not going to sell.' So they go through the exercise, they see that they're not going to get even close to" the amount of debt on the property, "and they pull it off the market."

Such a flip-flop can "taint the asset" by signaling that market interest in the property is weak, he said.

Bill Leseman, the chairman of Caldera Asset Management LLC, a real estate consulting firm with offices in Greenwood Village, Colo., and Atlanta, said that in the current market he expects lenders to hold most multifamily properties they take over for longer than the traditional 60 to 180 days.

"The concern … is that you'll have a large group trying to put product on the market with a very small buyer pool for the next 12 to 18 months," he said. "The capital out there is looking for very, very good deals" — bargains, in other words. "And I think the feeling is the sales market will just be in shambles for the next year and a half or so — perhaps two years."

Caldera was formed this year to help lenders figure out what to do with properties that wind up "on their doorstep one way or the other," Leseman said.

Lenders are "going to try to win back as much of the value that they can for their loan, and if that value is abnormally low in a nontransactional environment for the next two years, it may behoove them to … hold these things" for perhaps "two to three years."

But "if the asset is in a falling" market, or one that's "not going to move in the next three years … the direction we may give them is [that] it's better to go ahead and sell it now and take your lumps now versus taking your lumps three years from now."

Regulators' Concerns

Lawyers said regulations allow national banks and bank holding companies to hold seized real estate collateral for five years, a period that can be extended for up to another five years if certain conditions are met. But in general, banks are expected to dispose of real estate quickly.

Joseph Vitale, a partner with Schulte Roth, said supervisors have "competing concerns. The regulator is concerned about keeping the bank focused on its mission and keeping the wall between banking and commerce sacrosanct."

But regulators also "have a real concern with the safety and soundness and financial stability of the bank," he said. "If you truly can't sell it or you'd have to sell it at a fraction of what it's really worth, then it's really not in the interest of the regulator to force you to divest of a valuable asset at a loss."

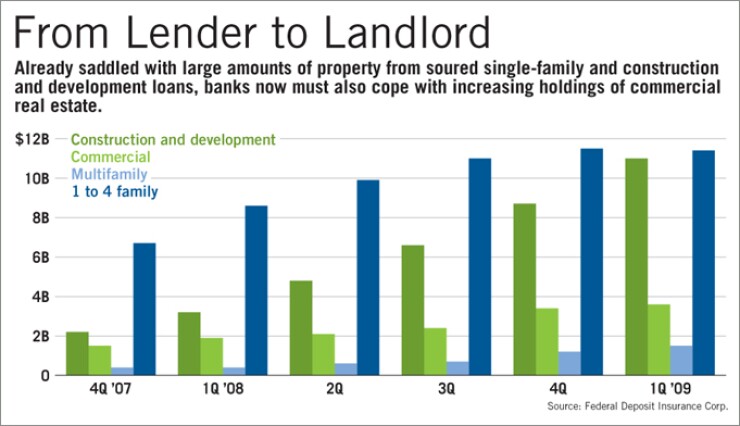

At the end of the first quarter, single-family properties were the biggest category of seized properties held by banks, at $11.4 billion, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Holdings from bad construction and development loans were a close second, at $11 billion. These increased 241.5% from the year prior, and have been accumulating rapidly in comparison with past-due loans, which increased 80.1%, to $82.1 billion during the same time, reflecting grim prospects for such projects and the difficulty disposing of them.

Overall holdings of foreclosed commercial and multifamily real estate properties are still relatively small, at $3.6 billion and $1.5 billion, respectively. (A big chunk of the multifamily — $494.4 million — is held by the ailing Corus Bankshares Inc.) Delinquency rates in these categories have lagged those of construction and development and single-family loans.

But problems are widely expected to build swiftly as massive amounts of debt come due amid constrained liquidity and tighter lending terms, and after steep price drops have pushed properties underwater. Also, MacDonald said, the market often lags trouble in the economy because it takes time for retrenching tenants to dump leases or for borrowers to exhaust cushions in loan contracts like interest-only periods.