-

Community bankers are starting to recoup some of the chargeoffs plaguing their balance sheets in recent years, with most recoveries tied to loans backed by commercial properties.

June 16 -

Many community banks have drifted in recent decades from core small-business and consumer lending toward financing commercial real estate.

June 7 -

Federal bank regulators need to update their commercial real estate guidance to bring standards more in line with how examiners treat loans following the crisis, an oversight report said Thursday.

May 19

Those who've been holding their breath for a commercial real estate meltdown may want to exhale.

Over the past two years, pundits have been predicting that commercial real estate would be the next proverbial shoe to drop, further wrecking bank balance sheets following the downturn in the residential housing market.

But by most accounts, a full-blown commercial real estate crisis has never materialized, and recent numbers suggest the forecast is improving.

"Most of the skeletons are out of the closet," says Dan Fasulo, managing director of Real Capital Analytics, a market research firm. "Everybody knows where the troubled loans reside and the tremendous recovery in values in major markets has moved many owners and lenders from a nightmare scenario to a situation where a nice majority of the debt has the ability to be restructured."

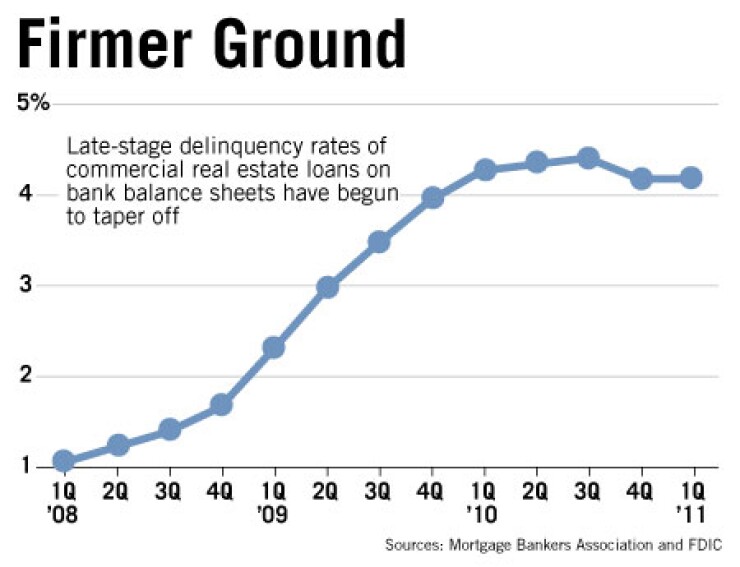

In recent quarters banks holding commercial and multifamily real estate loans have been feeling less pinched, according to a report released by the Mortgage Bankers Association earlier this month. Excluding construction loans, the share of commercial mortgages 90 days or more past due held steady at 4.18% in the first quarter after dropping from 4.41% in the third quarter of last year.

According to Fitch Inc., about $2.5 billion of previously delinquent securitized commercial mortgages were resolved or liquidated in June, the second highest total on record. Although there were $1.8 billion in new defaults, the unusually large number of liquidations brought down the overall delinquency rate for commercial mortgage-backed securities.

None of this is to say it's all smooth sailing from now on. A huge amount of commercial real estate is still underwater. Forty-nine percent of commercial mortgages maturing this year are larger than their collateral is worth, as are 63% of the loans maturing next year, according to Trepp, a research firm in New York.

That puts pressure on property owners to find cash to refinance, and on lenders to offer more generous terms. The future health of the market is also dependent on larger economic forces.

Although it has suffered from many of the same ailments that took down the residential market, such as overleveraged borrowers, "the commercial real estate market is much more sophisticated in its ability to make the necessary adjustments," says Taylor Grant, founding principal of California Real Estate Receiverships in Newport Beach, Calif.

"So overleveraged commercial real estate property is getting repositioned — that can include restructuring notes with existing borrowers, selling the note to a new entity, appointing a receiver, and eventually selling it, or they foreclose and put it in their REO department and sell it."

Data from Trepp shows that commercial real estate values are still off by 47% from their peak in 2007. However, Grant argues that low interest rates, coupled with beefed-up commercial servicing departments, have given banks the wherewithal to weather the hard times.

"Three years ago they didn't have the manpower and the capital to mark to market the property," he says. "They couldn't take the hit on the balance sheet of foreclosing, restructuring the note or selling it."

Matt Anderson, managing director of Trepp, argues that if it weren't for current low interest rates, many underwater borrowers would be sinking.

"It is a bit of a race against time, where you want the economic fundamentals and real estate fundamentals to improve," he says. "But more importantly, if interest rates start to increase, underwater borrowers with very low debt rates would see their payments increase."

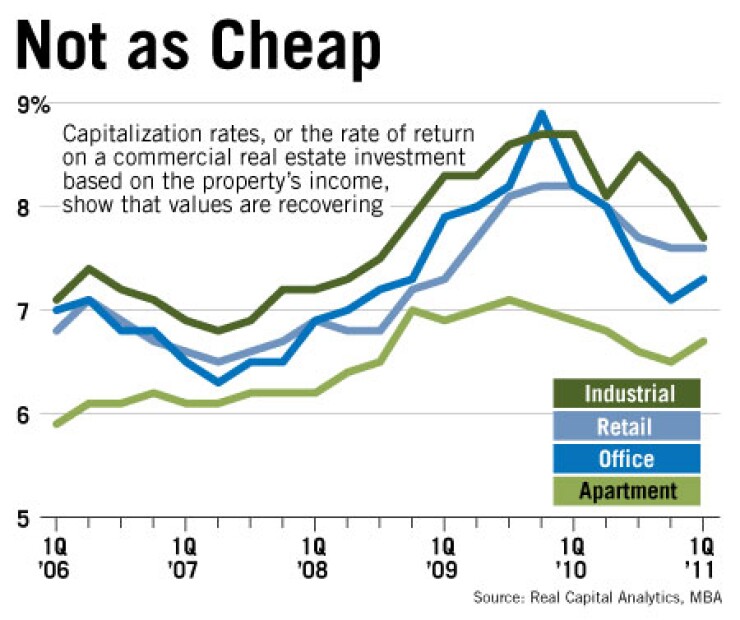

Values are recovering. According to Real Capital Analytics, commercial properties changed hands during the first quarter at an average yield of 7.2%. That's cheaper than the 6.5% levels seen at the top of the market in 2007, but richer than in the fourth quarter of 2009, when properties were priced to yield 8.1%.

In cities such as San Francisco, New York, and Boston, "the infill locations have become very desirable properties where there has been substantial improvement in where the rents are," says John Pelusi, executive managing director and managing member of Holliday Fenoglio Fowler L.P., a commercial mortgage banking firm. "And if you look at the multifamily sector here in the United States, as a general statement, you have very little new construction here in the U.S. and you have positive demographics and you are not building anything."

Banks have not suffered as badly from CRE loans as from other types of loans in the past few quarters. Even at the peak of commercial property delinquencies in 2010, the rate was lower than during the savings and loan crisis in the early 1990s.

And for commercial and multifamily loans, banks are reporting the lowest chargeoff rates of any loan type, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

"Certainly the chargeoff rates show that commercial and multifamily have been one of the more stable types of loans during this downturn," says Jamie Woodwell, the MBA's vice president of commercial real estate research.

A lot of the loans made during the bubble that are now underwater are coming due in the next five years. According to a report released in June by Trepp, 63% of the $360 billion of commercial real estate loans (including construction loans) held by banks, securitization trusts, and insurance companies due in 2012 are underwater.

That compares with the 49% of the $346 billion of mortgages that were due this year that were underwater. Trepp predicts the underwater share of the $327 billion of loans reaching maturity in 2015 will reach 75%.

But it will be easier for these commercial landlords to refinance than for strapped homeowners who took out subprime mortgages. Also, according to Trepp, if prices go up next year by 10%, only $137 billion of properties, or 38% of the mortgages maturing then, will be underwater. If prices hold steady, that figure rises to $227 billion of properties worth less than the debt encumbering them, or 63% of the maturing cohort.

Pelusi cautions that much depends on macroeconomic forces.

"Tell me where the unemployment rate is going to be, tell me where the interest rates are going to be," he says. "There are so many things that are beyond anyone's control relative to macroeconomic issues that are going to definitely play a role in how this thing works out."