-

Despite pressure from the Obama administration, banks are not going public with their concerns if the debt ceiling isn't increased, instead quietly urging members to wrap it up as they prepare contingency plans.

July 26

Fannie and Freddie could continue to operate even if the U.S. debt ceiling is not raised by August 2. But raising the ceiling alone, without a budget deal, would leave them — and a mortgage market that relies on their guarantees — vulnerable.

Despite improvements in their financial results, the government-sponsored enterprises need continued capital injections from the Treasury Department to avoid being unwound by their conservator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, according to the rating agency Fitch Inc. On average, the GSEs have been drawing $2 billion to $3 billion a quarter since 2010, say analysts at Barclays Capital.

"Fannie and Freddie right now given some legacy portfolio issues are likely to need ongoing support from the government," says James Moss, a Fitch analyst. "That flexibility is going to be compromised or lost if they don't raise the debt ceiling."

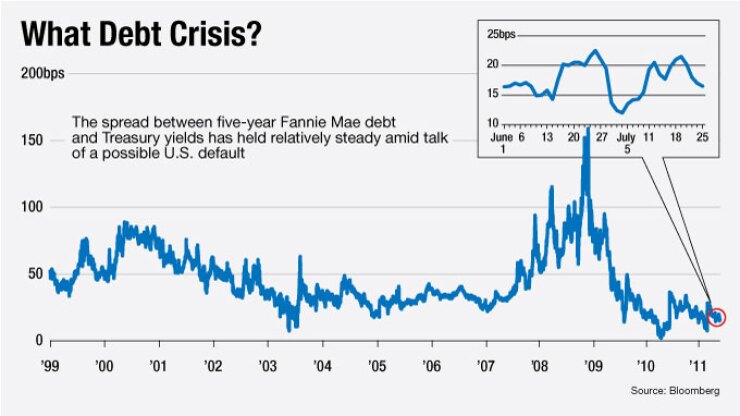

But some analysts say the possibility of the Treasury allowing the GSEs to become insolvent is close to zero. The market appears to believe this, given how little spreads have fluctuated between GSE debt and Treasury yields in recent weeks (see chart).

According to a report published last week by Barclays Capital, the GSEs appear to be able to weather a short-term debt ceiling crisis. The agreements under which Treasury invests in the GSEs allow for a significant amount of time before the capital injection is made. The deadline for the Treasury payments could be as far out as Sept. 30, according to Barclays, which would allow Congress and the president more time to dither.

Further, if the debt ceiling is not raised by the end of the third quarter, the Treasury Department can prioritize payments, Barclays says. And it would likely give GSE payments high priority, since not to do so would undoubtedly throw the mortgage markets into turmoil.

Moody's Investors Service Inc. has placed securities guaranteed by Fannie and Freddie as well as their senior debt on negative watch. A debt limit deal would preserve the GSEs' triple-A rating. But without a spending deal, Moody's would keep in place its negative outlook, which comes with a one-third probability of a downgrade within 18 to 24 months.

Standard & Poor's Corp. also has placed both the senior and the short-term debt of the GSEs on negative watch due to their need for capital injections from the Treasury. This could mean an S&P downgrade within three months if the government does not come up with a serious spending plan.

Chad Wandler, a Freddie Mac spokesman, said the GSE has a policy of not commenting on rating agency reports. And Fannie Mae did not respond by deadline.

At the very least, a downgrade of the U.S. credit rating would increase the risk premium that investors demand for mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by the GSEs. That in turn would raise mortgage rates, damping the already-soft demand for home purchases and refinancings.

"The GSEs are producing a triple-A mortgaged-backed security backed by the U.S. government," says Kurt Noyce, the president of Embrace Home Loans in Newport, R.I. "If the rating is lowered then the yield on those securities will be increased—so that will be felt across the board, and interest rates will rise for borrowers."

Aside from the GSEs, "there is really no market" for mortgage bankers to sell their loans, Noyce says, "so most lenders are selling their loans to Fannie and Freddie. So any interest rate increase in mortgage backed securities on the sale of those is going to be transferred to consumers."

Of course, there's also the Federal Housing Administration.

"In the short term, one can imagine that the FHA potentially might be able to backfill some of the demand that previously being satisfied by the GSEs," says Brian O'Reilly, president and managing director of the Washington consulting firm Collingwood Group and a former director at Fannie Mae. "But even in that case if the government only has a limited number of dollars I have no idea what Treasury's plans are going to be."

Indeed, the industry doesn't appear to be doing much planning for a U.S. default scenario — in part because it's so far out of the realm of anyone's experience. "Those securities have always been backed by a triple-A rating of the United States so I think that we are talking about new territory here," Noyce says.