Securitizations of consumer loans have rebounded, but whether the business can outlast the government sweeteners that have lured investors back to the market is an open question.

If an unsubsidized market does emerge, it is likely to be smaller and more sober than the previous one.

For starters, the basic architecture of securitization is being reshaped.

A crucial part of the Obama administration's proposed overhaul of financial regulation is a requirement that issuers retain an interest in securitizations.

In addition, new accounting rules will make it harder to move assets off balance sheets. Such transfers, which allowed financial institutions to hold less capital, were a big motivation of securitization in the past.

Still, the funding needs served by securitization are enormous, and some observers say basic reasons for the transactions — like debt pricing that can lower the cost of funds for lenders — remain in place.

"At the end of the day … I don't even know if issuers can fund themselves entirely without securitization," said Sanjay Sakhrani, an analyst at KBW Inc.'s Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. "I don't know if they could fund entirely with deposits."

Resurgence

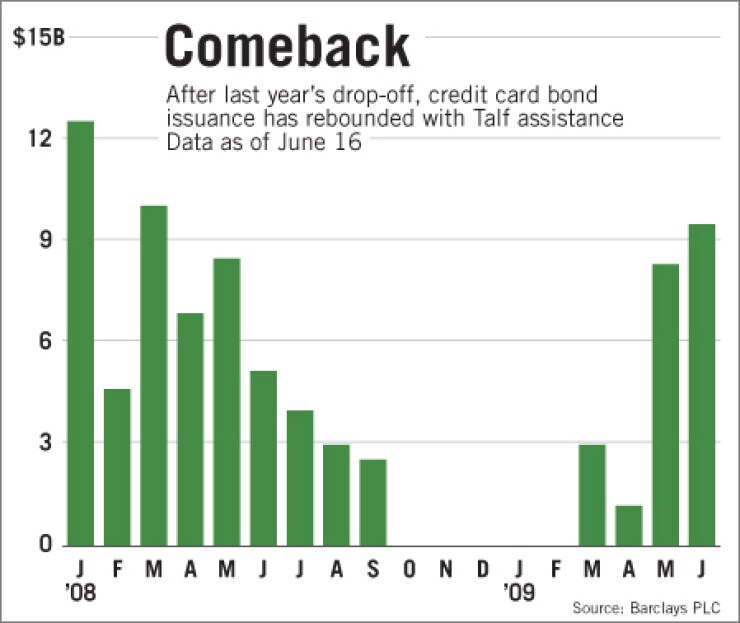

The issuance of asset-backed securities has rebounded sharply since the March launch of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility, a government program originally designed to provide up to $200 billion to buy bonds backed by consumer and small-business receivables.

In the credit card sector, issuance has recovered from a five-month drought and has totaled more than $22 billion since the Talf launch, according to Barclays PLC. At an annual rate, that is roughly in line with volumes from 2001 to 2006.

Credit card portfolios are shrinking, at least in part because of declining demand by consumers who have been hit by a sharp erosion in household wealth and are saving more. But the facility has spelled relief for an industry that has been working to shift toward deposits in addition to leaning on other emergency federal programs.

In a report published this month, Ajay Rajadhyaksha, the head of Barclays' U.S. fixed-income and securitized product strategy group, wrote that the increase in purchases of consumer asset-backed bonds by investors that did not use Talf loans and offerings outside the facility "at tight spreads is indicative of growing investor comfort" with the sector. Still, "the real test will be the ability of the market to continue to operate without the lure of cheap leverage."

Myron Glucksman, a structured finance consultant and a former managing director in Citigroup Inc., said Talf investments have "limited downside and a lot of upside" — the program boosts returns through leverage and caps losses at cash investments, because the loans from the Federal Reserve Board are nonrecourse.

Without that incentive, "investors would have a hard time right now getting comfortable, given that delinquencies are continuing to rise," Glucksman said.

Joshua Rosner, the managing director of Graham Fisher & Co., put it this way: "The only reason that we're seeing the liquidity in the market that we're seeing is because the government is offering outrageously large subsidized returns to institutional investors."

In a speech this month, William Dudley, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which runs the facility, said it was too soon to tell whether the program "will turn out to be a Band-Aid — providing temporary support to otherwise defunct securitization markets — or a bridge to an ultimately revived and vital securitization market."

Glucksman said a true comeback for asset-backed securities will depend on "how fast investors get comfortable with the risks on consumer assets" like credit cards and auto loans. "At some point, I think investors will understand both markets better, and there will be more clarity in terms of the losses."

Sakhrani agreed that "a better sense of where the inflection point is on credit" is needed.

Of course, some of the devices that absorbed copious amounts of asset-backed securities during the boom, like collateralized debt obligations and structured investment vehicles, were wiped out by the market crisis.

"I suspect that we will discover that some parts of the securitization market will return and prove viable, even without government support," Dudley said. "But other parts of these markets were fundamentally flawed, and they will not survive, nor should they."

Reg Reform

Jason Kravitt, a partner with Mayer Brown LLP and a longtime securitization lawyer, said regulatory reform must seek a difficult balance between re-establishing investor faith in asset-backed securities and allowing lenders to free up capital.

If regulators required issuers to retain too large an interest, or an interest "too low in the priority ladder, then you would completely defeat the ability of securitization to create extra credit, because it would be as if it stayed on your own balance sheet and you had to finance it yourself," Kravitt said.

The Obama administration's proposed requirement that issuers retain 5% of the credit risk "seems like a good number," but it depends on where in the credit structure the retained risk is required, he said.

The proposal is correct to give regulators the latitude to devise specific risk retention requirements, Kravitt said. "I don't think it's possible to write a 5% rule that applies to every structure, to every type of securitization."

Joseph Mason, a finance professor at Louisiana State University, said the popular notion that issuers should have more "skin in the game" gets it backward.

"The problem at the end of the day with securitization" was that "risk wasn't transferred, not that too much risk was transferred," he said. "The old ideal of securitization … was full risk transfer, where the deal truly stands on its own and has sufficient credit enhancement to truly absorb even Great Depression-level crisis losses."

But beginning in the 1990s, investors did not price properly for risk, since they came to believe that support for securitizations from issuers would always be forthcoming, Mason argued. That became evident as credit losses accelerated and issuers withdrew their support "en masse." The crisis was caused "by that option of support."

Instead of mandating stronger ties between issuers and the bonds, "we can move back to a paradigm of bulletproof deals that stand alone," he said. "This would create predictable and stable funding markets, just like banks prefer predictable and stable insured deposit markets, instead of less predictable and more unstable brokered deposit markets."

It is true that "the risk transfer can never be truly perfect," Mason said. "No repeated transaction to a small number of borrowers can ever be truly off-balance-sheet," because the reputation of that small group of issuers is on the line.

"The question is, do we want to completely collapse leverage, or do we want to just pull back a little bit, require a de minimus capitalization of securitized pools to represent the possible relationships through representations and other means?" he asked. "I would suggest that the latter of those two is preferable, to preserve the good aspects of securitization as best we can."

Support Measures

In the current recession, nonmortgage asset-backed bonds have also been tested by the extent to which issuers have been willing to compensate for unexpectedly heavy credit deterioration with new support.

The actions of most have been reassuring to investors in card-backed bonds. American Express Co., Bank of America Corp. and Citigroup Inc. have formed and retained new bond classes that are designed to absorb losses before those held by other investors.

But last month Advanta Corp., a Spring House, Pa., small-business card issuer, decided that it was in its financial interests to allow its card-backed bonds to unwind prematurely and to stop lending to account holders — essentially to close shop and jettison its securitization program — rather than trying to safeguard investors by devoting additional resources to prop up the securities.

(The chargeoff rate in Advanta's pool of securitized receivables had more than doubled in the past year, to 17.3%.)

"What Advanta did can happen again, potentially," Sakhrani said. "I'm just not sure it would happen with at least the top 10 issuers. I think they would provide enough support to make sure that the securitizations see themselves through. … To the extent that an issuer is well capitalized or is able to capitalize itself, my sense is they'd want to support the securitization."

Accounting Changes

According to Kravitt, "balance sheet management" had been a major objective for financial companies that securitized loans.

"If you were doing it either solely for that purpose, or that was part of the mix of decisions that tips the balance, that's gone," he said.

The standards issued last week for off-balance-sheet accounting, Financial Accounting Statements 166 and 167, will make the industry smaller, Kravitt said. "I think there will be less securitization."

Glucksman said accounting rule changes are helping to push the market toward "something similar to covered bonds."

These debt securities, which have long been an important part of the capital markets in Europe, are similar to asset-backed bonds in that they are tied to pools of loan collateral. The main difference is that the debt and the collateral are reflected on the lender's balance sheet.

On-balance-sheet securitizations have also been used in the United States; the Minneapolis retailer Target Corp. has used them for its credit card program, for instance.

"You're left with isolating assets on balance sheet, but in a vehicle that relies on the assets and on the credit of the originating institution," Glucksman said.

Economic Pillar

Experts said there are still rationales for securitization. For example, there is the benefit of having another market to use for funds.

"It's best to exhaust all funding options and to have a diverse funding profile," Sakhrani said.

On a conference call with clients Thursday, Kravitt said securitization is vital to the economy. "What's the alternative to securitization? Because if you're going to think about either destroying securitization or regulating it out of existence, you have to have an alternative."

Two weeks ago, he said, he put the question about a possible alternative to an official at the U.K. Financial Services Authority. That official "thought it would be a banking market funded materially on the basis of retail deposits — with developed economies in the world having a standard of living about equal to 1960."