-

An Office of the Comptroller of the Currency emerging risk report said underwriting for indirect auto and leveraged loans is cause for concern.

June 25 -

The Great Recession allowed banks to gain ground on the finance arms of automakers. Now they're making investments aimed at keeping that edge.

August 23 -

Auto loans to the least creditworthy borrowers have rebounded, but they are still below the levels reached in the early- and mid-2000s, the New York Fed finds.

August 14

Has the U.S. auto lending market become overheated? The answer to that question depends on which parts you inspect after popping the hood.

Auto finance is definitely booming, thanks largely to strong investor demand for an asset class that performed unexpectedly well during the Great Recession. In the first three months of the year, automobile lending at banks grew by an impressive 9.9% year-over-year, far outpacing other consumer loan products, according to recent report by Moody's Investors Service.

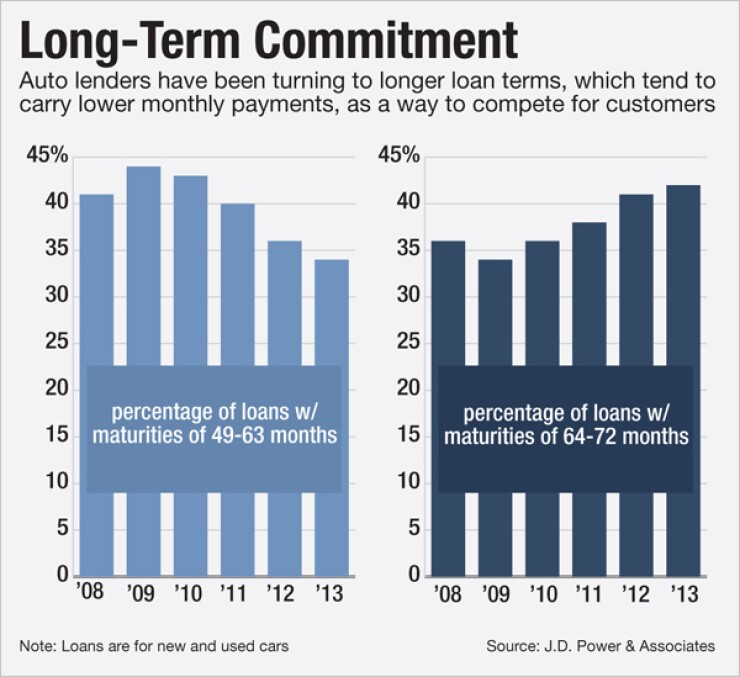

In order to sustain the growth, banks and other auto lenders have made it easier for car shoppers to qualify for a loan. Low credit scores and small down payments are less likely to be impediments than they used to be. And longer loan terms which make the borrower's monthly payments more affordable, but also increase the chances that the lender will take a big loss have become commonplace.

But whether the easing of credit standards represents a worrisome omen or a healthy return to the pre-recession norm is a matter of intense debate. Melinda Zabritiski, senior director of automotive finance at Experian, sees reasons to be sanguine as well as cause for concern.

"We're not really seeing subprime originations at unprecedented levels," she says. But when asked about the expanding length of loan terms, she notes, "They're pretty much at all-time highs."

Here's the case for pessimism about the auto finance market, followed by the argument for optimism.

Why to Be Worried

Historically, auto loans have carried maximum loan terms of five years. That reflected the fact that cars depreciate rapidly. If a borrower defaulted three years into the loan, the lender might take a loss, depending on the value of the repossessed vehicle. But any loss would likely be manageable, since the loan was just a year or two from being paid off.

But as competition among auto lenders has intensified over the last couple of years, some have begun offering six-year and even seven-year loans. When loan terms get extended, a borrower who qualifies to make monthly payments of $400 can afford to buy a pricier vehicle.

Today, 72 months is the most common term on loans for the purchase of both new and used cars, according to Experian. Longer loan terms open lenders to the possibility of larger losses when loans go bad.

"I think that is certainly troubling," says Mike Wall, director of automotive analysis at IHS Automotive, in reference to expanding loan terms.

In a

In an interview, Bob Piepergerdes, the OCC's director for retail credit risk, noted that used-car values are currently at elevated levels, based on historical standards, which adds another element of risk. "You have loans based upon higher used-car values that may or may not hold together over the term of the loan," he says.

Piepergerdes periodically talks to bankers about auto lending, and they tell him that competition is compelling them to loosen their credit standards. "What they say is, if they don't make the loan, others will," he explains.

The situation carries certain echoes of the housing bubble of the 2000s. One parallel is that in both instances, lenders are taking greater risks in order to satisfy the demand of investors in the secondary market.

Mack Caldwell, a Moody's senior vice president who leads the firm's auto asset-backed securities ratings team, says that auto loan securitizations are routinely made larger in order to meet the demand from investors.

"I think the appetite is pretty strong," he says.

Why the Fears May be Exaggerated

One key reason why investor demand for securitized auto loans has been so strong is that the sector weathered the financial crisis quite well. That history bodes well for the future.

"Consumers need automobiles, and that was proven in the recession," says Mike Buckingham, senior director of the automotive finance practice at J.D. Power. "That was the No. 1 debt that was paid by the consumer."

And despite the loosening credit standards in recent months, auto loan delinquencies have not risen appreciably. For auto loans originated in May through July of last year, only 1.4% were 90 days or more past due in the subsequent months, according to Fair Isaac.

And there are limits to the parallels between today's auto sector and the housing bubble of the mid-2000s. For example, auto lenders don't make interest-only or negative amortization loans.

"All lenders understand that autos are a depreciating asset. So there were no exotic financing structures in place," Buckingham notes.

In addition, while auto lenders have been making more loans to consumers with low credit scores than they were a few years ago, subprime originations are not at unprecedented levels. (Subprime borrowers often pay interest rates in the teens, while prime borrowers' rates can be in the low single digits.)

In the first quarter of this year, borrowers in the two lowest bands of creditworthiness made up about 14% of all auto loan originations, according to data from Experian. That compares to more than 19% in the first quarter of 2007.

Finally, for secondary market investors in auto loans, there are protections built into the deals, even if default rates rise appreciably.

"If losses are higher than expected," says Moody's Caldwell, "it won't be of any consequence to investors."

Of course, that's one more echo of the subprime housing bubble.