For banks still holding on to longtime problem assets, now might be the time to consider selling.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, banks were saddled with scores of soured loans. But even if institutions were looking to sell these assets, and investors were interested in purchasing them, banks were often constrained by capital level requirements from taking the necessary write-offs associated with fire sales.

Now capital levels are higher so banks would be better able to absorb losses, and investors are still hungry to buy distressed assets for good prices. But banks have mostly been reluctant to complete loans sales.

That could be a mistake if credit quality were to take a turn for the worse, and there are a few indicators that new problems could be on the horizon.

“If you are selling assets today, you are probably being more tactical,” said Jeff Davis, a managing director in Mercer Capital’s financial institutions group. “You are thinking strategically as the economic cycle ages, and you are trying to take some chips off the table.”

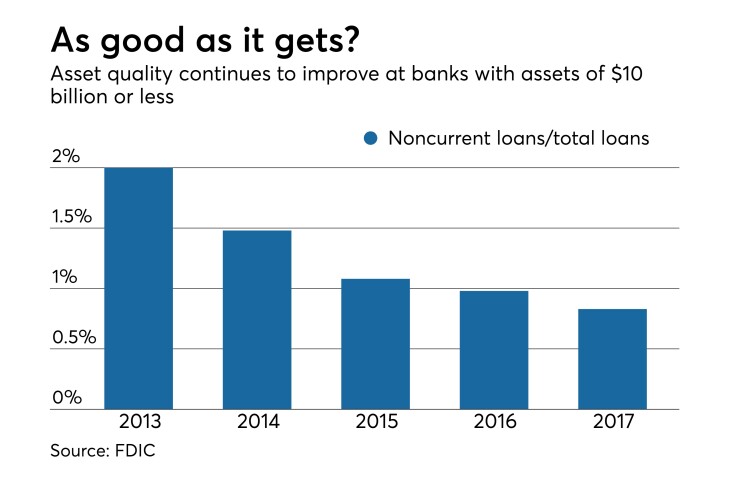

Credit quality has improved significantly since the depths of the recession. Problem assets for all banks totaled $193 billion at Dec. 31, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. That figure included other real estate owned, assets that were 30 to 89 days past due and at least 90 days late, and those in nonaccrual status.

That is down from a peak of $581 billion at year-end in 2009, according to FDIC data.

Still the recent number is roughly 42% higher than the $136 billion recorded in 2006, according to data from the FDIC.

“Banks still have a pretty elevated level of classified assets because many of them didn’t fully pull off the Band-Aid half a decade ago,” said Jon Winick, CEO Clark Street Capital. “You are starting with a decent sized workout universe to begin with. Now there are new credits coming in.”

There are signs that credit quality could weaken, though certainly no one is predicting an imminent financial collapse. For instance, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York said in a report on household debt earlier this year that credit card delinquencies increased “notably.” The percent of credit card balances that were at least 90 days late rose to 7.55% in the fourth quarter from 7.14% a year earlier, according to the report.

Winick said an uptick in credit card delinquencies can be an early indicator of wider problems to come. Generally, business customers have more resources to keep their loans current when trouble starts to brew.

Interest rate hikes may also put pressure on certain commercial customers, especially in the commercial real estate portfolio. For instance, multifamily housing has been overbuilt in some cities, meaning that supply has out stripped demand. Owners of these buildings could have problems increasing rents as a result. That may become a problem as their loans come due and they get new financing at higher interest rates, Winick said.

Owners of retail properties in some areas may also struggle to raise rents on tenants either because of long-term leases or because the market won’t support such hikes, Winick said. Retail is also facing pressure from broader changes in consumer behavior as more people shop online.

“The 900-pound gorilla is Amazon,” said Lynn David, CEO of Community Bank Consulting Services. “What it is doing to retail is phenomenal. It has to be a concern to everyone. I don’t care if it is paper towels. You can now order it online from Amazon and get them shipped for free.”

To be sure, there have been banks in recent months that have looked to sell loans, both performing ones and problem credits. Substandard loans that banks consider selling may still be performing, but there could be other concerns, such as a covenant being breached.

A bank may decide to unload good loans if they are concerned about concentration levels, are looking to exit a certain business line or decide they could redeploy the funds into a higher-yielding asset.

PacWest Bancorp in Beverly Hills, Calif., announced in December that it would sell cash flow loans worth roughly $1.5 billion as it looked to wind down its commercial lending origination operations related to healthcare, technology and general purposes. PacWest President and CEO Matt Wagner said in the release that the $25 billion-asset company made the decision “for both cyclical and competitive reasons.”

Other banks looked to pare back their exposure in energy after oil prices tumbled.

Still, many banks are deciding to hold onto credits, even ones that are in danger of becoming distressed. This lack of supply could be helping to drive up pricing for the loans that do become available, said Kip Weissman, a partner at Luse Gorman.

“We are at the top of a credit cycle and that means there’s less of a supply,” Weissman said. “More loans are performing, and it is a countercyclical industry.”

Michael Britvan, a managing director in loan sale and asset sale group at Mission Capital Advisors, has observed banks are currently less willing to sell loans at a loss, likely due to the potential impact on earnings. This decision seems counterintuitive as the market is awash in liquidity, resulting in the narrowest bid-ask spread in recent history, he said.

”Performing, subperforming or nonperforming debt is in vogue,” he said. “We have been in an extended bull market run, therefore investors are targeting fixed-income investment, targeting assets they view to be slightly less risky and less correlated with the broader market.”

Matthew Howe, vice president of special assets at Lakeside Bank in Chicago, said he has seen better pricing on stressed commercial loans than in recent years. He said the bank is seeing bids between 85% to 90% of a loan’s outstanding balance, compared with offers in the low 80s just a few years ago.

Even though the $1.6 billion-asset Lakeside is not suffering from the credit problems that plagued the industry after the recession, management still tries to be proactive in managing its loan portfolio. That means even in a strong economy sometimes the bank offloads distressed credits.

Howe says one reason driving buyers' interest in distressed assets is that foreclosures are moving faster through the court system. That can eliminate some of the uncertainty for potential buyers of troubled commercial real estate loans.

“It has been aggressive,” Howe said. “There is an appetite in the marketplace for distressed and for performing loans.”