-

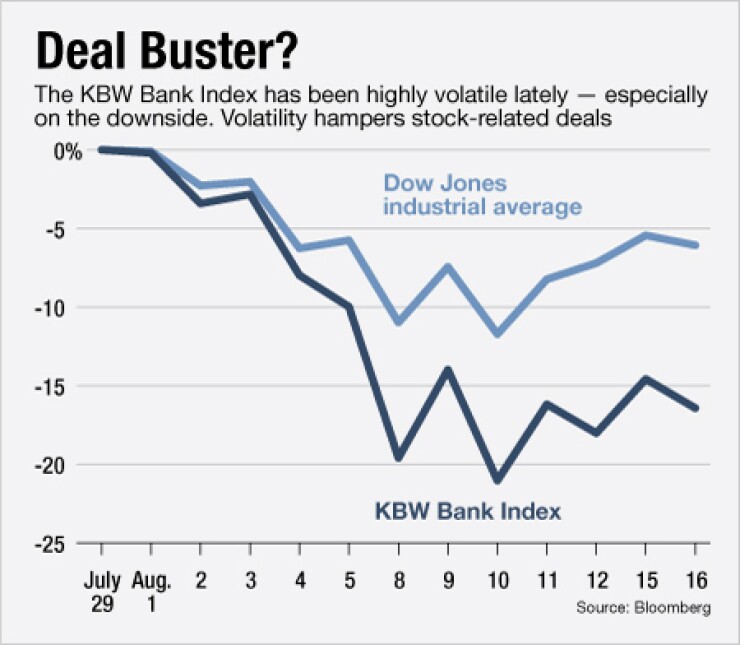

One bank postponed its initial public offering because of recent volatility, and others stock offerings could be delayed for weeks or months. It was bad timing for banks trying to get the jump on weakened competitors.

August 15

Recent economic chaos has delayed banks' near-term merger plans but gives weaker institutions even more reasons to sell the franchise in the long run.

Prospects have dimmed for an acceleration of deals in the second half of 2011 after a modest uptick in volume in the second quarter.

Most mergers have some kind of stock component. Issuing shares to the selling bank or to investors as part of a capital raise to pay for the deal are infeasible when share prices are swinging wildly. Deals that were in the works when stocks plummeted last week are probably on ice.

Yet the Federal Reserve announcement that it will not raise interest rates for two years effectively put a noose on bank margins, making consolidation among the country's 7,500 banks likelier than ever. Consumers and businesses are not borrowing, and returns are dwindling on the huge batches of government-backed securities the industry has been gobbling up.

Deals are necessary to grow in this kind of environment. If you do not grow, you will have to sell. There are too many banks and not enough borrowers.

"Writ large — the big picture is consolidation is going to happen," said James Kaplan, partner and chair of the Midwestern banking practice of law firm DLA Piper.

The new interest rate guidance may also reshape which banks become buyers and where they can do deals.

The prospect of a long spell of low rates may force would-be buyers with big portfolios of increasingly low-yielding securities to rethink their plans — particularly about buying into new markets. Low rates mean tighter margins. That means deals only make financial sense if they deliver big cost savings from eliminating redundant branches or people.

Deal returns will hinge even more cost savings, given the toll low rates should take on growing post-merger profits by selling new loans and services. The biggest savings come from buying the rival down the block.

So ambitious expansion plays along the lines of M&T Bank Corp.'s push in recent years into Baltimore and the surrounding region, or First Niagara Financial Group Inc.'s foray into New England, may be off the table for now. If it is not in-market, it probably will not happen.

The good news for banks interested in buying other banks is that weak rates cut both ways.

Moderately healthy institutions hoping to earn their way to continued independence may now decide to sell out sooner, rather than later. A number of fundamentals on that front have not changed in recent weeks. Bank liquidity is at an all-time high and real estate and consumer debt problems seem to have reached an inflection point.

Though merger activity may now be more stop than go for the foreseeable future, pent-up demand should only continue to swell, said Tom Mitchell, an analyst with Miller Tabak & Co. that covers regional banks.

Suppose the economy stabilizes and the KBW Bank Index of 24 large and midsize banks regains the 15% it has lost since the end of July, Mitchell said.

If that happens, "you could fairly quickly see fresh appetites for deals because, strategically, if you are not going to grow loans you've basically got a problem in this low-interest environment," Mitchell said. "You need to find some way to create cost savings and one of the best ways to do that is to do deals."

Kip Weissman, a partner with law firm Luse Gorman Pomerenk & Schick P.C., Washington, said the handful of deals his firm is working on have become mired in recent weeks in negotiations over caps on how many shares the buyer may have to issue.

In the long term, however, banks may now have more reasons than ever to become sellers.

"It's introduced fear, and fear is a motivator for sellers and boards of directors," Weissman said. "The rates present challenges for the whole industry. But for a lot of sellers, they are going to experience more margin concentration. It's another reason to maybe head for the exit."

John Adams, director of mergers for Sheshunoff & Co. in Austin, Texas, is bullish on the long-term outlook for bank mergers, too.

Fewer banks are becoming severely distressed due to delinquent borrowers, he said, noting that number of banks with nonpeforming assets of 6% or more declined for the first time in about two years, to less than 1,200 in the second quarter.

Fears about future loan problems are the top deal roadblock, he said, and the worst has passed on that front.

"A lot of the bankers feel like they have gotten the surprises out of the way and it is just a matter of dealing with what they've got," he said. "They understand their balance sheet for the first time in a while and as a buyer and a seller that has implications."