New York City will now require banks that want to hold city deposits to provide detailed plans about what they're doing to root out discrimination in their lending and employment practices.

The city will also, for the first time, accept public comments online or in person as part of its biennial process to determine which banks are eligible.

Both actions are designed to help New York make decisions about where to put its deposits.

The transparency measures, which were announced Friday morning by the New York City Banking Commission, come less than a year after the city said it would

The decision to cut ties with Wells Fargo was one factor in the commission's decision to reevaluate its process for designating city depositories, City Comptroller Brad Lander said in an interview Friday. Lander is one of three members of the banking commission, along with New York City Mayor Eric Adams and the city's department of finance commissioner, Preston Niblack.

"There were several key steps that weren't part of the process," Lander said. "We thought it was important to develop a new set of certifications and forms to provide information about ways they are working to meet the needs of our communities, and create a public comment opportunity."

Every two years, banks must apply to become approved depositories for the city's billions of dollars of public funds. Each bank must supply a list of documents by March 1 and, in May, the banking commission determines designated depositories by majority vote.

There are currently 28 banks approved to hold the city's deposits. The list includes several of the nation's largest banks — names like JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, U.S. Bancorp and PNC Financial Services Group — as well as midsize and smaller regionals such as KeyCorp, M&T Bank and Webster Financial, and a few foreign-owned banks.

Wells Fargo remains on the list as a designated bank, but it does not hold any New York City deposits.

The city's designated banks have already been made aware of the enhanced information they must provide, said Louis Cholden-Brown, senior advisor and special counsel for policy and innovation at the comptroller's office.

Public comments can be submitted throughout an online portal until May 25, the same day that a public hearing will be held to collect in-person comments, after which the banking commission will determine which banks will be designated depositories, Cholden-Brown said.

Some community organizations and advocacy groups said the city's new policies are a step in the right direction when it comes to putting deposits into banks that are practicing fair and equitable lending in all communities. They encouraged the city to do even more.

"We hope this is just a first step in deepening community engagement, scrutiny and transparency in this public process," Barika Williams, executive director of the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, said in a press release announcing the changes.

The city's enhanced process is "a welcome development," but there's more work to do, Andy Morrison, associate director of the advocacy group New Economy Project, said in an interview.

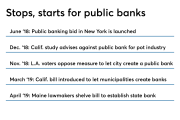

His group has long been advocating for a public banking framework at the state and city levels. Public banks are lending and depository institutions that are owned and managed by a governmental entity.

"What's really needed to ensure that public deposits are being used for the public good and held by an accountable institution is a public bank," Morrison said. "We've been very clear about that being the ultimate solution."

There's a chance that New York City's current list of 28 designated banks will dwindle now that banks must disclose more information, Lander said.

"Banks will have to, at minimum, make affirmations and fill out forms and provide information," Lander said. "And I guess it's possible that some will choose not to do it."