As central banks around the world hold borrowing rates at record- low levels to ward off further economic damage from the coronavirus pandemic, the cost to the global banking industry could prove to be steep.

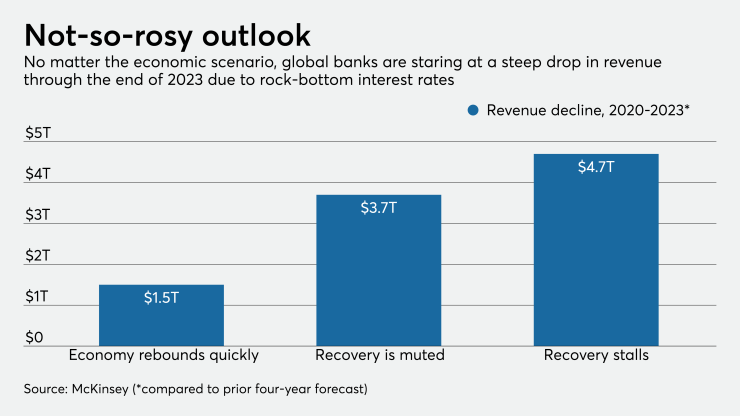

A recent report from the consulting firm McKinsey estimates banks around the world could lose out on $3.7 trillion between the start of this year and the end of 2023, when compared with earlier projections.

That’s assuming the economy recovers modestly from the pandemic. If the recovery takes longer, global banks could miss out on as much as $4.7 trillion in revenue, McKinsey predicts.

Meanwhile, reserve builds meant to cushion against loan losses could pass levels last seen during the 2008-09 financial crisis, according to the report.

Given these twin challenges, banks will have little choice but to boost production through volume and reduce expenses by upgrading technology, shrinking headcount throughout their organizations and shedding unneeded real estate, according to the report.

“For some banks, these measures may not be enough,” said Marie-Claude Nadeau, a San Francisco-based McKinsey partner and the author of the report. “Mergers might be the best way out. Some banks are already pursuing M&A before things get worse.”

Revenues from deposits are expected to slow and income from corporate and commercial business lines will shrink as well as debt is refinanced into lower rates, according to the report, which analyzed the financials of more than 1,600 banks worldwide.

Banks could also lose out on revenue collected from payments if consumer spending doesn’t rebound. Corporate banking, too, could take a hit even if the business of facilitating mergers and acquisitions picks up because the value of companies would likely fall.

Banks spent 2020 adding billions in loan-loss reserves, but government programs are expiring and breaks lenders have offered on debt payments are running out. A second stimulus package remains stalled, and without additional help, banks could face the prospect of adding more to their reserves before beginning to release them. Banks with higher concentrations of loans to transportation, energy, and leisure companies with winter months ahead, could need even more capital to guard against losses.

“As temporary programs evolve or wind down, banks will likely reckon with the fuller force of the crisis,” according to the McKinsey report.

Banks that can’t do enough to improve efficiency or meaningfully grow revenue may pursue acquisitions, and some are already doing so, according to McKinsey.

Here in the U.S., bank M&A started slowly in 2020 but has picked up of late.

Just this week, the year's biggest banking deal was struck, with Huntington Bancshares in Columbus, Ohio,

Pittsburgh-based PNC Financial Services Group agreed in November to

PNC hopes to do this by taking out BBVA’s higher expenses from operating under an international company and boosting revenue from the expansion into places like Texas, where BBVA has had a challenge cross-selling products like home loans to its checking account customers or wealth management accounts to its business clients.

“Go into the markets, cross-sell the clients, bring more products to bear, grow new clients, take the costs out that are in the core shell of running this thing because we don't need those,” Demchak said. “And the model works.”

Some industry experts are still expecting a spring rebound that could bring new opportunities for loan growth as companies try to pick up production and replenish their inventories to meet renewed demand.

But there is some concern if a turnaround doesn’t materialize quickly. One in four small-business owners said in a survey released by the National Federation of Independent Business on Tuesday that they would have to close their doors in the next six months if the economy doesn’t improve soon.

Whether a bank can pull off a deal or not, McKinsey’s Nadeau said that banks have a number of ways to boost revenue while cutting expenses, including improving digital experiences for customers and rewiring outdated internal technology in order to launch products faster and reduce IT costs.

In the report, Nadeau also said banks should make permanent some of the changes they’ve made as employees have been forced to work from home. Bank tellers at branches that have closed could be rerouted to much-needed customer support positions. A few banks, Nadeau said, have “declared war” on excessive meetings and reports. Quicker, more efficient decisions are being made over video conferences with fewer steps to what before had been a labyrinth of a process.

The pandemic may have revealed a prime cost-saving option of managing with fewer decision makers if reorganizations are made before the business can get back to normal.

“Time is of the essence,” Nadeau said, “before people revert to old and still-comfortable behaviors.”