-

In what would be the first acquisition in its 50-year history, Peoples State Bank in Wausau, Wis., is planning to buy the $108 million-asset Marathon State Bank in nearby Marathon City for $5.6 million.

March 19 -

In what would be its largest acquisition in more 15 years, UnionBanCal Corp. in San Francisco is buying Pacific Capital Corp. in Santa Barbara, Calif., for about $1.5 billion in cash.

March 12 -

Prices fell and the pace of dealmaking slowed last month, but March started off strong with another big deal in Texas.

March 9

Sometimes you can have too much of a good thing — including capital.

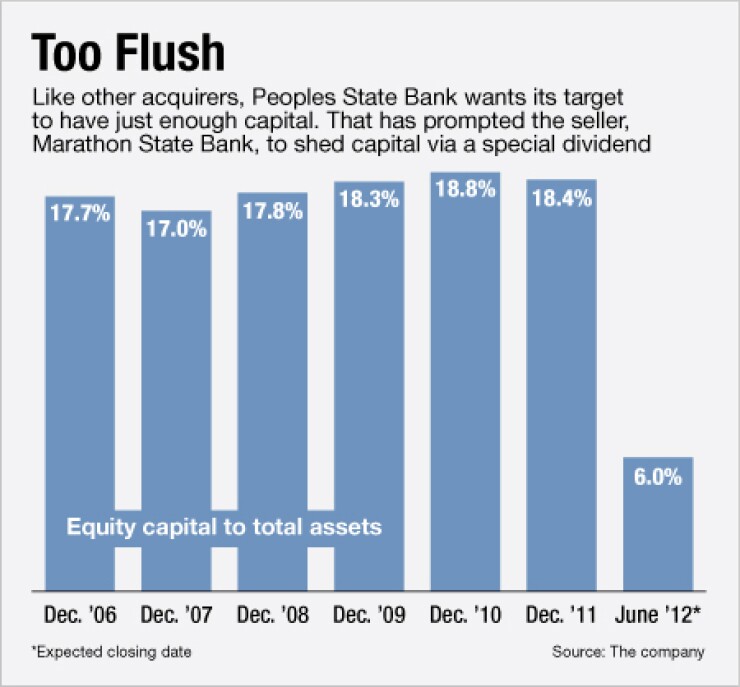

Marathon State Bank in Marathon City, Wis., gets that. Unlike many community banks, Marathon State's capital ratios have been through the roof during the recession. But the badge of honor was a dead weight when the bank went to sell itself to PSB Holdings Inc., of Wausau, Wis. So much so that PSB felt compelled to ask its target to shed some capital as part of its

Using a special dividend, Marathon State will return $14.3 million of equity to shareholders, reducing its equity-to-assets ratio to 6%, from 18.4% at Dec. 31.

Industry experts say the structure once was popular but had largely fallen out of vogue during the financial crisis and ensuing capital crunch.

"This type of transaction went away for a while because the concept of excess capital didn't really exist for a few years," says John Blaylock, an associate director at Sheshunoff & Co. Investment Banking. "In the deals we saw in 2009 and 2010, the capital was absorbed by writedowns."

Blaylock said excess capital could come back in fashion. There is more capital in the system, and there are bankers looking for an exit. The past few weeks have

"I think people are feeling better about M&A," Blaylock says. "March has roared like a lion. We are seeing what we expected to see last year. Everyone is talking about doing something — buying, selling, combining."

A capital payout is mutually advantageous for buyers and sellers. For sellers, a special dividend lets shareholders get a more favorable tax treatment for the bulk of the consideration. Special dividends are treated as capital gains taxed at a 15% rate. Acquisition proceeds are treated as ordinary income, which can be taxed at up to 35%.

That was particularly important to Marathon State's older shareholder base, says Frank Gassner, the $108 million-asset bank's chairman and president. "A lot of our shareholders are really high in age, and this was a good way to liquidate," he says. "It is very competitive environment, so when the right situation arose, we decided to take that fork in the road."

On the opposite end of the table, sellers typically don't need the extra cash. Marathon State, with a nonperforming asset ratio of 0.01%, doesn't need to have its loan book marked down, and the $622 million-asset PSB Holdings already had high capital levels. At Dec. 31 the buyer's equity-to-assets ratio was 10.04%.

PSB Holdings is buying the Marathon at book value, so it could have paid the seller's shareholders roughly $20 million itself, but its executives say this method simplifies the deal.

"The special dividend eliminates the excess capital and gives us a more normal purchase metric," says Scott Cattanach, PSB Holdings' chief financial officer. "Because of their risk profile, the bank just doesn't need that much capital."

The structure should allow Marathon State, which PSB Holdings plans to initially keep separate from its Peoples State Bank, to start its new life with much higher profitability metrics, says Daniel Trigg, a partner at McGladrey & Pullen LLP in Chicago.

"The return on equity would be outstanding," Trigg says. "It would probably be 8% to 12%."

Marathon State's return on equity was 2.84% for 2011, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Besides acquiring a profitable and soon-to-be leaner bank, Cattanach says it was a chance to pick up a longtime rival in Marathon City. "We started our location in 1990 and have been competing against them for 20 years. It has been difficult to get a foothold against the hometown bank," Cattanach says. "But being the bank literally across the street should ease the customer transition."

Advisors say the return of this structure is notable, though it is just one of several structures that will likely be dusted off as consolidation increases. Meanwhile, they say, it is important to remember that deals start with willing parties, not mechanics.

"This is one tool to use, but every deal is structured on a case-by-case analysis," says Peter Wilder, a lawyer at Godfrey & Kahn SC in Milwaukee who represents PSB Holdings. "It starts with deciding you want to get out and finding a buyer. Once you make the decision to get out, you figure out the exact structure."