This story was the recipient of a 2024 Folio Eddie journalism award.

The Jefferson Avenue commercial district in Buffalo, New York, is anchored by a supermarket.

There are dozens of other businesses and services along the 12-block corridor — a couple of bank branches, a library, a coffee shop, gas stations, a small plaza with a dollar store and a primary care clinic and a business incubator for entrepreneurs of color.

But Tops Friendly Markets, the only grocery store on Buffalo's vast East Side, is the center of activity. More than just a place to buy food, pick up medications and use an ATM, the store is a communal gathering space in a predominantly Black neighborhood that, for generations, has been segregated, isolated and disenfranchised from the wealthier — and whiter — parts of the city.

Which explains how it came to be the site of a mass shooting on a spring day in May of last year. On that Saturday, a gunman, who lived 200 miles away in another part of the state, drove to Jefferson Avenue and went into Tops, and in just a few minutes killed 10 people, injured three and inflicted mass trauma across the community.

It is a scenario that has sadly, and repeatedly, played out in other parts of the country that have experienced mass shootings. But this one came with a twist: The gunman's intention was to kill as many Black people as possible.

To achieve that, he specifically targeted a ZIP code with one of the highest percentages of Black residents in New York state. All 10 who died that day were Black.

"The mere fact that someone can research, 'Where will the greatest number of Black people be … on a Saturday morning,' that's not by chance," said Franchelle Parker, a community organizer and executive director of Open Buffalo, a nonprofit focused on racial, economic and ecological justice. "That's not a mistake. It's a community that's been deeply segregated for decades."

The day of the shooting, Parker, who grew up in nearby Niagara Falls, was driving to Tops, where she planned to buy a donut and an unsweetened iced tea before heading into the Open Buffalo office, which is located a block away from Tops. The mother of two had intended to complete the mundane task of cleaning up her desk — "old coffee cups and stuff" — after a busy week.

She saw the news on Twitter and didn't know if she should keep driving to Jefferson Avenue or turn around and go back home. She eventually picked the latter.

When she showed up the next day, there were thousands of people grieving in the streets. "The only way that I could explain my feeling, it was almost like watching an old war movie when a bomb had gone off and someone's in, like, shell shock. That's how it felt," said Parker, vividly recounting the community's collective trauma in a meeting room tucked inside of Open Buffalo's second-story office on Jefferson Avenue.

Almost immediately following the May 14, 2022, massacre, which was the second-deadliest mass shooting in the United States last year, conversations locally and nationally turned to the harsh realities of the East Side and how long-standing factors that affect the daily life of residents — racism, poverty and inequity — made the community an ideal target for a white supremacist.

Now, more than a year after the tragedy, there is growing concern that not enough is being done fast enough to begin to dismantle those factors. And amid those conversations, there are mounting calls for the banking industry — whose historical policies and practices helped cement the racial segregation and disinvestment that ultimately shaped the East Side — to leverage its collective power and influence to band together in an effort to create systemic change.

The ideas about how banks should support the East Side and better embed themselves in the neighborhood vary by people and organizations. But the basic argument is the same: Banks, in their role as financiers and because of the industry's history of lending discrimination, are obligated to bring forth economic prosperity in disinvested communities like the East Side.

I know banks are often looked upon sort of like a panacea, but I don't particularly see it that way. I think others have a role to play in all of this.

"Banks have been very good at providing charitable contributions to the Black community. They get an 'A' for that," said The Rev. George Nicholas, an East Side pastor who is also CEO of the Buffalo Center for Health Equity, a four-year-old enterprise focused on racial, geographic and economic health disparities. "But doing the things that banks can do in terms of being a catalyst for revitalization and investment in this community, they have not done that."

To be sure, banks' ability to reverse the course of the community isn't guaranteed — and there is no formula to determine how much accountability they should hold to fix deeply entrenched problems like racism. Several Buffalo-area bankers said that while the Tops shooting heightened the urgency to help the East Side, the industry itself cannot be the sole driver of change.

"There are a lot of institutions … that can certainly play a part in reversing the challenges that we see today," said Chiwuike "Chi-Chi" Owunwanne, a corporate responsibility officer at KeyBank, the second-largest bank by deposits in Buffalo. "I know banks are often looked upon sort of like a panacea, but I don't particularly see it that way. I think others have a role to play in all of this."

A long history of segregation

How the East Side — and the Tops store on Jefferson Avenue — became the destination for a racially motivated mass murderer is a story about racism, segregation and disinvestment.

Even as it bears the nickname "the city of good neighbors," Buffalo has long been one of the most racially segregated cities in the United States. Of the 114,965 residents who live on the East Side, 59% are Black, according to data from the 2021 U.S. Census American Community Survey. The percentage is even higher in the 14208 ZIP code, where the Tops store is located. In that ZIP code, among 11,029 total residents, nearly 76% are Black, the census data shows.

The city's path toward racial segregation started in the early 20th century when a small number of job-seeking Black Americans migrated north to Buffalo, a former steel and auto manufacturing hub at the far northwestern end of New York state. Initially, they moved into the same neighborhoods as many of the city's poorer immigrants and lived just east of what is today the city's downtown district. As the number of Blacks arriving in Buffalo swelled in the 1940s, they were increasingly confronted with various housing challenges, including racist zoning laws and restrictive deed covenants that kept them from buying homes in more affluent white areas.

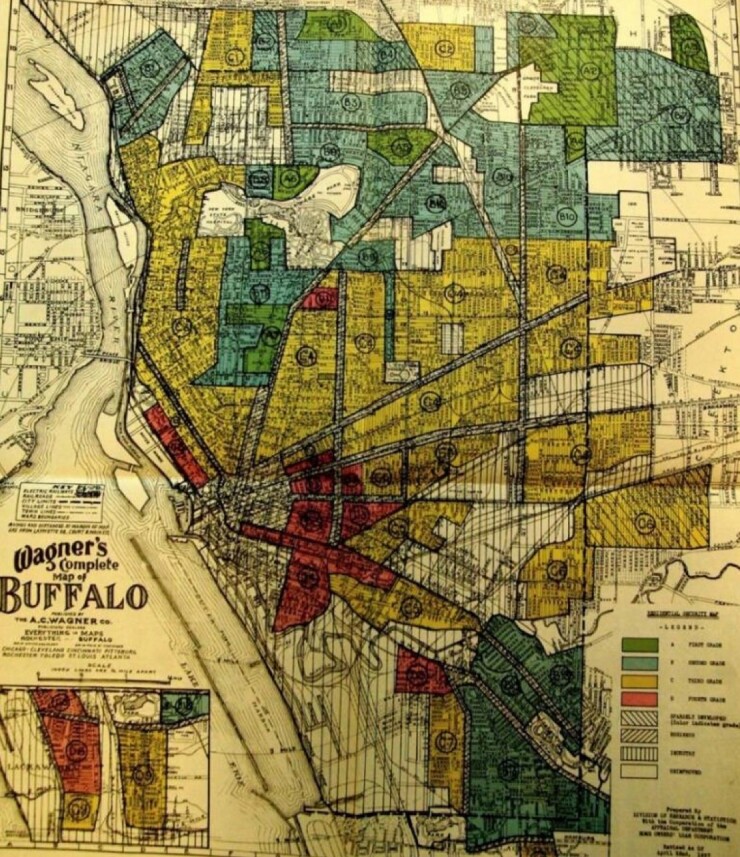

Black Buffalonians also faced housing discrimination in the form of redlining, the practice of restricting the flow of capital into minority communities. In 1933, as the Great Depression roiled the economy, a temporary federal agency known as the Home Owners' Loan Corporation used government bonds to buy out and refinance mortgages of properties that were facing or already in foreclosure. The point was to try to stabilize the nation's real estate market.

As part of its program, HOLC created maps of American cities, including Buffalo, that used a color coding scheme — green, blue, yellow and red — to convey the perceived riskiness of making loans in certain neighborhoods. Green was considered minimally risky; other areas that were largely populated by immigrant, Black or Latino residents were labeled red and thus determined to be "hazardous."

"The goal was to free up mortgage capital by going to cities and giving banks a way to unload mortgages, so they could turn around and make more mortgage loans," said Jason Richardson, senior director of research at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, an association of more than 750 community-based organizations that advocates for fair lending. "It was kind of a radical concept and it has evolved over the decades into our modern mortgage finance system."

The Federal Housing Administration, which was established as a permanent agency in 1934, used similar methods to map urban areas and labeled neighborhoods from "A" to "D," with "A" considered to be the most financially stable and "D" considered the least. Neighborhoods that were largely Black, even relatively stable ones, were put in the "D" category.

The result was that banks, which wanted to be able to sell mortgage loans to the FHA, were largely dissuaded from making loans in "risky" areas. And Buffalo's East Side, where the majority of Blacks were settling, was deemed risky. Unable to get loans, Blacks couldn't buy homes, start businesses or build equity. At the same time, large industrial factories on the East Side were closing or moving away, limiting job opportunities and contributing to rising poverty levels.

"Today what we're left with is the residue of this process where we've enshrined … a pattern of economic segregation that favors neighborhoods that had fewer Black people in them and generally ignores neighborhoods that had African Americans living in them," Richardson said.

Case in point: Research by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition shows that three-quarters of neighborhoods that were once redlined are low- to moderate-income neighborhoods today, and two-thirds of them are majority minority communities.

Adding to the division between Blacks and whites in Buffalo was the construction of a highway called the Kensington Expressway. Built during the 1960s, the below-grade, limited-access highway proved to be a speedy way for suburban workers to get to their downtown jobs. But its construction cut off the already-segregated East Side even more from other parts of the city, displacing residents, devaluing houses and destroying neighborhoods and small businesses.

As a result of those factors and more, many Black residents have become "trapped" on the East Side, according to Dr. Henry Louis Taylor Jr., a professor of urban and regional planning at the University at Buffalo. In 1987, Taylor founded the UB Center for Urban Studies, a research, neighborhood planning and community development institute that works on eliminating inequality in cities and metropolitan regions. In September 2021, eight months before the Tops shooting, the Center for Urban Studies published a report that compared the state of Black Buffalo in 1990 to present-day conditions. The conclusion: Nothing had changed for Blacks over 31 years.

As of 2019, the Black unemployment rate was 11%, the average household income was $42,000 and about 35% of Blacks had incomes that fell below the poverty line, the report said. It also noted that just 32% of Blacks own their homes and that most Blacks in the area live on the East Side.

"Those figures remain virtually unchanged while the actual, physical conditions that existed inside of the community worsened," Taylor told American Banker in an interview in his sun-filled office at the center, located on the University at Buffalo's city campus. "When we looked upstream to see what was causing it, it was clear: It was systemic, structural racism."

Banks' moral obligations

As the East Side struggled over the decades with rampant poverty, dilapidated housing, vacant lots and disintegrating infrastructure, banks kept a physical presence in the community, albeit a shrinking one. In mid-2000, there were at least 20 bank branches scattered across the East Side, but by mid-2022, the number had fallen to around 14, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s deposit market share data. The 14 include four new branches that have opened since early 2019 — Northwest Bank, KeyBank, Evans Bank and BankOnBuffalo.

The first two branches, operated by Northwest in Columbus, Ohio, and KeyBank, the banking subsidiary of KeyCorp in Cleveland, were requirements of community benefits agreements negotiated between each bank and the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. In both cases,

Evans Bank opened its first East Side branch in the fall of 2021. The office is located in the basement of an $84 million affordable senior housing building that was financed by Evans, a $2.1 billion-asset community bank headquartered south of Buffalo in Angola, New York.

Banks have been very good at providing charitable contributions to the Black community. They get an 'A' for that. But doing the things that banks can do in terms of being a catalyst for revitalization and investment in this community, they have not done that.

On the community and economic development front, banks have had varying levels of participation. Buffalo-based M&T Bank, which holds a whopping 64% of all deposits in the Buffalo market and is one of the largest private employers in the region, has made consistent investments in the East Side by supporting Westminster Community Charter School, a kindergarten through eighth-grade school, and the Buffalo Promise Neighborhood, a nonprofit organization focused on improving access to education in the city's 14215 ZIP code.

Currently, Buffalo Promise Neighborhood operates four schools. In addition to Westminster, it runs Highgate Heights Elementary, also K-8, as well as two academies that serve children ages six weeks through pre-kindergarten. Twelve M&T employees are dedicated to the program, according to the Buffalo Promise Neighborhood website. The bank has invested $31.5 million into the program since its 2010 launch, a spokesperson said.

Other banks are making contributions in other ways. In addition to the Jefferson Avenue branch and as part of its community benefits plan, Northwest Bank, a $14.2 billion-asset bank, supports a financial education center through a partnership with Belmont Housing Resources of Western New York. Meanwhile, the $198 billion-asset KeyBank gave $30 million for bridge and construction financing for Northland Workforce Training Center, a $100 million redevelopment project at a former manufacturing complex on the East Side that was partially funded by the state.

BankOnBuffalo's East Side branch is located inside the center, which offers KeyBank training in advanced manufacturing and clean energy technology careers. A subsidiary of $5.6 billion-asset CNB Financial in Clearfield, Pennsylvania, BankOnBuffalo's office opened a month after the shooting. The timing was coincidental, but important, said Michael Noah, president of BankOnBuffalo.

"I think it just cemented the point that this is a place we need to be, to be able to be part of these communities and this community specifically, and be able to build this community up," Noah said.

In terms of public-private collaboration, some banks have been involved in a deeper way. In 2019, New York state, which had already been pouring $1 billion into Buffalo to help revitalize the economy, announced a $65 million economic development fund for the East Side. The initiative is focused on stabilizing neighborhoods, increasing homeownership, redeveloping commercial corridors including Jefferson Avenue, improving historical assets, expanding workforce training and development and supporting small businesses and entrepreneurship.

In conjunction with the funding, a public-private partnership called East Side Avenues was created to provide capital and organizational support to the projects happening along four East Side commercial corridors. Six banks — Charlotte, North Carolina-based Bank of America, the second-largest bank in the nation with $2.5 trillion of assets; M&T, which has $203 billion of assets; KeyBank; Warsaw, New York-based Five Star Bank, which has about $6 billion of assets; Northwest and Evans — are among the 14 private and philanthropic organizations that pledged a combined $8.4 million to pay for five years' worth of operational support, governance and finance, fundraising and technical assistance to support the nonprofits doing the work.

Laura Quebral, director of the University at Buffalo Regional Institute, which is managing East Side Avenues, said the banks were the first corporations to step up to the request for help, and since then have provided loans and other products and education to keep the program moving.

Their participation "is a signal to the community that banks cared and were invested and were willing to collaborate around something," Quebral said. "Being at the table was so meaningful."

Richard Hamister is Northwest's New York regional president and former co-chair of East Side Avenues. Hamister, who is based in Buffalo, said banks are a "community asset" that have a responsibility to lift up all communities, including those where conditions have arisen that allow it to be a target of racism like the East Side.

"We operate under federal charters, so we have an obligation to the community to not only provide products and services they need but also support when you go through a tragedy like that," Hamister said. "We also have a moral obligation to try to help when things are broken … and to do what we can. We can't fix everything, but we've got to fix our piece and try to help where we can."

In the wake of a tragedy

After the massacre, there was a flurry of activity within banks and other organizations, local and out-of-town, to respond to the immediate needs of East Side residents. With the community's only supermarket closed indefinitely, much of the response centered around food collection and distribution. Three of M&T's five East Side branches, including the Jefferson Avenue branch across the street from Tops, became food distribution sites for weeks after the shooting. On two consecutive Fridays, Northwest provided around 200 free lunches to the community, using a neighborhood caterer who is also the bank's customer. And BankOnBuffalo collected employee donations that amounted to more than 20 boxes of toiletries and other items that were distributed to a nonprofit.

At the same time, M&T, KeyBank and other banks began financial donations to organizations that could support the immediate needs of the community. KeyBank provided a van that delivered food and took people to nearby grocery stores. Providence, Rhode Island-based Citizens Financial Group, whose ATM inside Tops was inaccessible during the store's temporary closure, installed a fee-free ATM near a community center located about a half-mile north of Tops, and later put a permanent ATM inside the center that remains there today. And M&T rolled out a short-term loan program to provide capital to East Side small-business owners.

One of the funds that benefited from banks' support was the Buffalo Together Community Response Fund, which has raised $6.2 million to address the long-term needs of the East Side.

Bank of America and Evans Bank each donated $100,000 to the fund, whose list of major sponsors includes four other banks — JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, M&T and KeyBank. Thomas Beauford Jr., a former banker who is co-chair of the response fund, said banks, by and large, directed their resources into organizations where the dollars would have an immediate impact.

"Banks said, 'Hey, you know … it doesn't make sense for us to try to build something right now. … We will fund you in the work you're doing,'" said Beauford, who has been president and CEO of the Buffalo Urban League since the fall of 2020. "I would say banks showed up in a big way."

Fourteen months later, banks say they are committed to playing a positive role on the East Side. For the second year, KeyBank is sponsoring a farmers' market on the East Side, an attempt to help fill the food desert in the community. Last fall, BankOnBuffalo launched a mobile "bank on wheels'' truck that's stationed on the East Side every Wednesday. The 34-foot-long truck, which is staffed by two people and includes an ATM and a printer to make debit cards, was in the works before the shooting, and will eventually make four stops per week around the Buffalo area.

Evans has partnered with the city of Buffalo to construct seven market-rate single family homes on vacant lots on the East Side. The relationship with the city is an example of how banks can pair up with other entities to create something meaningful and lasting, more than they might be able to do on their own, said Evans President and CEO David Nasca.

The bank has "picked areas'' where it can use its resources to make a difference, Nasca said.

"I don't think the root causes can be ameliorated" by banks alone, he said. "We can't just grant money. It has to be within our construct of a financial institution that invests and supports the public-private partnership. … All the oars [need to be] pulling together or this doesn't work."

'Little or no engagement with minorities'

All of these efforts are, of course, welcomed by the community, but there is still criticism that banks haven't done enough to make up for their past contributions to segregating the city. And perhaps more importantly, some of that criticism centers on banks failing to do their most basic function in society — provide credit.

In 2021, the New York State Department of Financial Services

The department said its investigation showed the lower percentage was not due to "excessive denials of loan applications based on race or ethnicity," but rather that "these companies had little or no engagement with minorities and generally made scant effort to do so."

"The unsurprising result of this has been that few minority customers or individuals seeking homes in majority-minority neighborhoods have made loan applications … in the first instance."

Furthermore, accusations of redlining persist today, even though the practice of discriminating in housing based on race was outlawed by the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

In 2014, Evans was accused of redlining by the New York State Attorney General, which said the community bank was specifically avoiding making mortgage loans on the East Side. The bank, which at the time had $874 million of assets,

The bank has a greater presence on the East Side today, but that's because it has grown in size, not because it is trying to make up for previous accusations of redlining, he said.

"Ten years ago, our involvement [on the East Side] certainly wasn't what you're seeing today," Nasca said. "We were looking to participate more, but we were participating within our means and our reach. As we have grown, we have built more resources to be able to do more."

Shortly after accusations were made against Evans, Five Star Bank, the banking arm of Financial Institutions in Warsaw, New York, was

KeyBank is currently being

KeyBank denied the allegations. In March, the coalition

Beyond providing more credit, some community members believe that banks should be playing a larger role in addressing other needs on the East Side. And the list of needs runs the gamut from more grocery stores to safe, affordable housing to infrastructure improvements such as street and sidewalk repairs.

Alexander Wright is founder of the African Heritage Food Co-op, an initiative launched in 2016 to address the dearth of grocery store options on the East Side, where he grew up. Wright said that while banks' philanthropic efforts are important, banks in general "need to be in a place of remediation" to fix underlying issues that the industry, as a whole, helped create. (After publication of this story, Wright left his job as CEO of the African Heritage Food Co-Op.)

Aside from charitable donations, banks should be finding more ways to work directly with East Side business owners and entrepreneurs, helping them with capital-building support along the way, Wright said. One place to start would be technical assistance by way of bank volunteers.

"Banks are always looking to volunteer. 'Hey, want to come out and paint a fence? Want to come out and do a garden?'" Wright said. "No. Come out here and help Keshia with bookkeeping. Come out here and do QuickBooks classes for folks. Bring out tax experts. Because these are things that befuddle a lot of small businesses. Who is your marketing person? Bring that person out here. Because those are the things that are going to build the business to self-sufficiency.

"Anything short of the capacity-building … that will allow folks to rise to the occasion and be self-sufficient I think is almost a waste," Wright added. "We don't need them to lead the plan. What we need them to do is be in the community and [be] hearing the plan and supporting it."

Parker, of Open Buffalo, has similar thoughts about the role that banks should play. One day, soon after the massacre, an ATM appeared down the street from Tops, next to the library that sits across the street from Parker's office. Soon after the ATM was installed, Parker began fielding questions from area residents who were skeptical of the machine and wanted to know if it was legitimate. But Parker didn't have any information to share with them. "There was no outreach. There was no community engagement. So I'm like, 'Let me investigate,'" she said. "I think that's a symptom of how investment is done in Black communities, even though it may be well-intentioned."

As it turns out, the temporary ATM belonged to JPMorgan Chase. The megabank has had a commercial banking presence in Buffalo for years, but it didn't operate a retail branch in the region until last year. Today it has four branches in operation and plans to open another two by the end of the year, a spokesperson said.

After the Tops shooting, the governor's office reached out to Chase asking if the bank could help in some way, the spokesperson said in response to the skepticism. The spokesperson said that while the Chase retail brand is new to the Buffalo region, the company has been active in the market for decades by way of commercial banking, private banking, credit card lending, home lending and other businesses.

In addition to the ATM, the bank provided funding to local organizations including FeedMore Western New York, which distributes food throughout the region.

"We are committed to continuing our support for Buffalo and helping the community increase access to opportunities that build wealth and economic empowerment," the spokesperson said in an email.

In the year since the massacre, there has been some progress by banks in terms of their interest in listening to the East Side community and learning about its needs, said Nicholas. But he hasn't felt an air of urgency from the banking community to tackle the issues right now.

"I do experience banks being a little more open to figuring out what their role is, but it's slow. It's slow," said Nicholas. The senior pastor of the Lincoln Memorial United Methodist Church, located about a mile north from Tops, Nicholas is part of a 13-member local advisory committee for the New York arm of Local Initiatives Support Coalition, or LISC. The group is focused on mobilizing resources, including banks, to address affordable housing in Western New York, specifically in the inner city, as well as training minority developers and connecting them to potential investors, Nicholas said.

Of the 13 members, seven are from banks — one each from M&T, Bank of America, BankOnBuffalo, Evans and KeyBank, and two members from Citizens Financial Group. One of the priorities of LISC NY is health equity, and the fact that banks are becoming more engaged in looking at health disparities is promising, Nicholas said. Still, they have more work to do, he said.

"I need them to think more on how to strengthen and build the economy on the East Side and provide leadership around that, not only to provide charitable things, but using sound business and banking and community development principles to say, 'OK, if we're going to invest in this community, these are the types of things that need to happen in this community,' and then encourage their partners and other people they work with … to come fully in on the East Side."

Some bankers agree with the community activists.

"Putting a branch in is great. Having a bank on wheels is great," said Noah of BankOnBuffalo. "But if you're not embedded in the community, listening to the community and trying to improve it, you're not creating that wealth and creating a better lifestyle for everyone."

What could make a substantial difference in terms of banks' impact on the community is a combination of collaboration and leadership, said Taylor. He supports the idea of banks leading the charge on the creation of a comprehensive redevelopment and reinvestment plan for the East Side, and then investing accordingly and collaboratively through their charitable foundations.

"All of them have these foundations," Taylor said. "You can either spend that money in a strategic and intentional way designed to develop a community for the existing population, or you can spend that money alone in piecemeal, siloed, sectorial fashion that will look good on an annual report, but won't generate transformational and generational changes inside a community."

Banks might be incentivized to work together because it could mean two things for them, according to Taylor: First, they'd have an opportunity to spend money in a way that would have maximum impact on the East Side, and second, if done right, the city and the banks could become a model of the way to create high levels of diversity, equity and inclusion in an urban area.

"If you prove how to do that, all that does is open up other markets of consumption all over the country because people want to figure out how to do that same thing," Taylor said.

Some of that is already happening, at least on a bank-by-bank case, said KeyBank's Owunwanne. Through the KeyBank Foundation, the company is able to leverage different relationships that connect nonprofits to other entities and corporations that can provide help.

"I see this as an opportunity for us to make not just incremental changes, but monumental changes … as part of a larger group," Owunwanne said "Again, I say that not to absolve the bank of any responsibility, but just as a larger group."

Downstairs from Parker's office, Golden Cup Coffee, a roastery and cafe run by a husband and wife team, and some other Jefferson Avenue businesses are trying to build up a business association for existing and potential Jefferson-area businesses. Parker imagined what the group could accomplish if one of the banks could provide someone on a part-time basis to facilitate conversations, provide administrative support and coordinate marketing efforts.

"In the grand scheme of things, when we're talking about a multimillion dollar [bank], a part-time employee specifically dedicated to relationship-building and building out coalitions, it sounds like a small thing," Parker said. "But that's transformational."

Kevin Wack contributed to this story